FutureSheLeaders (19)

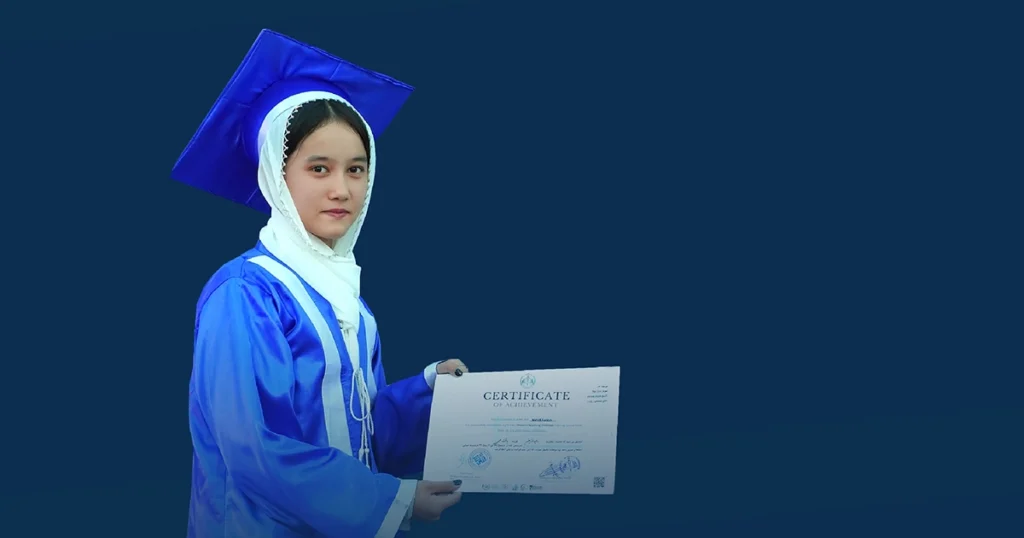

This week’s episode of FutureSheLeaders brings you the story of a star shining through the darkest night – the story of Fatema Mahdawi.

A girl born in Mazar-e-Sharif, who as a child painted her world with tiny hands and sweet smiles, and greeted life with love and laughter.

At the age of nine, she met the monster of cancer – a cruel illness that attacked her legs and threatened to take away her strength and stability. From that moment on, her journey became a fight – a fight not just against disease, but for life itself.

It was a journey marked by wounds and exile – from the streets of Mazar to the wards of Shaukat Khanum Hospital in Lahore. Long nights filled with bitter medicines, hair that fell out, eyebrows that disappeared… but one flame never went out in her heart: the love for life.

Fatema came back – not just to the alleyways of Mazar-e-Sharif, but to the hidden pathways of life.

She returned to learning, to dreaming, to hoping.

When the gates of school were slammed shut on Afghan girls, she did not sit still.

In her school, in Cluster Education, in the Empowerment sessions, and in the circle of FutureSheLeaders, she carved a new path forward – transforming pain into purpose, failure into stepping stones, and tears into bright, defiant smiles.

Today, Fatema speaks to us – not only of her triumphant battle with cancer, but also of her proud and unwavering stand to protect the dream of female leadership in a society that resists the very existence, name, and memory of women.

She began her journey of change with one simple step:

By working with younger girls, by teaching, by nurturing -and like a bird that finds its wings even in the storm, she rises and flies toward a brighter future.

Come and listen to Fatema’s story – the story of life, and the deep, determined love for it.

Royesh: Fatima, hello – and welcome to Future She Leaders.

Fatima: Hello, Ustad! Good day to you. Thank you so much. I’m really happy to be one of those who get the chance to talk with you here in Future She Leaders. It’s such a joy to spend this hour with you, and I hope that everyone who watches this video can find something inspiring in my story – or learn a little from my experiences.

Royesh: I’d like to start today’s conversation with you – about yourself. Please give us a short introduction: when and where you were born, a bit about your family – your parents, sisters, and brothers – and how each of them has shaped or influenced your life.

Fatima: Sure, Ustad. My name is Fatima, I’m 17 years old, and I was born on May 23, 2008, in Mazar-e-Sharif. I’m the second child in our family – there are seven of us altogether: my parents, four sisters, and one brother. My family, especially my parents, have played a really important role in my life. From my early childhood through all the difficult times I’ve faced, they have always supported me – every step of the way.

Royesh: Usually, when we ask people your age about their families, many say, “My family never supported me,” or “They only created problems and restrictions for me.” They often say, “I’ve walked this path all on my own.” What about you? What would you say?

Fatima: Ustad, everyone’s life is different, and each person’s view of their family is unique. So, their answers might not be the same. But I believe that no parent ever wants their child to suffer or fail. Sometimes the limits they set come from their way of thinking – from how well they understand their children and how well their children understand them.

I’ve seen parents who have worked really hard for their children, but because the child hasn’t yet reached that level of understanding, they feel that their parents’ decisions are restrictions.

However, from another point of view – yes, it’s true – some parents, especially in Afghan society, may create barriers for daughters my age or for young people who have new and different dreams. It really depends on the parents’ mindset and their circumstances.

Royesh: Now, if we look at your own life – would you describe your relationship with your parents as friendly? Would you say that even when they set limits, it came from love and care, not from hostility? That maybe they didn’t always like your choices, but it was never out of cruelty or opposition?

Fatima: Yes, exactly. Sometimes I make decisions, but I always discuss them with my parents first. I never make any decision without consulting my parents – because I’ve come to realize that they have far more experience than I do. They’ve seen more of the world and learned much more from it than I have. That’s why I trust them completely. Whatever decision they make for me, I respect it and follow it. If they say, “Don’t do this,” I don’t. If they say, “Do this,” I’ll definitely do it.

Sometimes I might react emotionally – when they disagree with me, I might feel upset. But after an hour or so, I sit and think about it and realize, “Yes, they’re right.” They say the right things, and I should listen.

Maybe at first, I don’t respond well, but later I always go back, apologize, and promise to follow their advice.

Royesh: Your parents belong to a different generation. Let’s say they’re in their 40s, 50s, or 60s – that means they’ve lived decades before you.

But you live in a very different time. Your wants and your understanding of the world are not the same as theirs. They often base their advice on experiences from 40 or 50 years ago – so should you always obey them? Does respecting them mean you have to live by the expectations of that older world? And if you don’t, does that mean you’re being disrespectful?

Fatima: Yes, the time they lived in and the time I live in are completely different – almost like two different worlds, from east to west. But still, I believe parents usually make wiser decisions than we do. Because right now, we’re still growing and learning. My parents always say, “You young people decide too quickly – you don’t always think things through or consider all sides before choosing.” We young people aren’t always farsighted – but our parents are, because they’ve lived much longer and seen much more of life.

Still, I can say that sometimes when I make a decision, I do think it through carefully from every angle. If I truly believe in it and have considered its future outcomes, then even if my parents disagree, I try to stay firm on it.

If the decision is wise and well-thought-out, I stand by it. One of my recent decisions was a bit controversial at home – but in the end, I managed to make it happen. And I’m confident that, eventually, it will bring a good result.

Royesh: Like what? What decision?

Fatima: It was about registering online through a Duolingo link. The registration fee was quite high, so my parents were a bit against it. They said, “Maybe it’s not reliable.”

But I was confident in my decision. I told them, “You have to pay this fee because I’ve made up my mind, and I’m going to stand by it.”

Finally, when they paid, my mother smiled and said, “So, you made your decision and made us follow it!” I laughed and told her, “There must be something I’ve seen or understood that made me insist so much.”

Of course, I was a little scared too- I worried, “What if it’s not genuine? What if I lose my credibility in the family?” But in the end, I was glad- because my decision turned out to be right and worthwhile.

Royesh: Now, your parents speak from their past experiences – but the past is gone. As the Arabs say, “Ma maza mada” – what’s gone is gone. Your parents want to apply their past experiences to your life, while you’re looking toward the future. So how do you resolve this tension between the past and the future?

Fatima: Our past and future are tied to our present. The things we experience in the past become lessons for our future. For example, we’ve all had hard experiences before, and those experiences directly shape who we are today.

If someone hasn’t gone through challenges in the past, they might make weaker or less-wise decisions now. A clear example is a student who never faced hardship or studied seriously – when new opportunities come, they might not know how to use them.

That’s why the lessons we learn from the past affect our present, and the choices we make in the present shape our future. So, I believe the past, the present, and the future are all deeply connected to one another.

Royesh: Yes, the past, present, and future are connected – but sometimes they also conflict with one another. For example, your father might say, “Our past experiences tell us you should dress this way, behave this way, and follow these rules.”

But you might say, “Based on how I see the future, I need to take these risks and make my own choices – nothing bad will happen.”

This creates a real tension – one side values the past and tries to act by its lessons, while the other looks forward and believes in the future. Sometimes this contradiction can lead to a dead end. How do you resolve this conflict?

Fatima: When it comes to this conflict, since I belong to the new generation, I tend to choose the future. I think more about where I’m going than where I’ve been. The future is the place where I’ll live –

the past is where I used to live. What’s gone is gone; I can’t change it anymore.

So now, I try to keep both my past and future in mind – thinking about how many more years I might live, and what kind of life I want to build for myself. When I imagine my future, I ask: “Will I live a good life or not?” That’s what really guides my choices today.

Royesh: Now, if you wanted to express this in the language of empowerment, how would you describe it? Let’s say it’s the conflict between reality and the ideal. Your parents talk from the side of reality: they say life is hard, society is difficult and unfair, there are real dangers – and none of this is imaginary. But you speak from the side of the ideal – your dreams, your hopes, and your vision of the future. Bridging this gap – between what is and what should be – is itself an empowerment exercise.

So, as a student of empowerment, how do you reconcile this conflict between reality and the ideal?

Fatima: What I’ve learned – and what I keep in mind now – is that we should first look at our current situation realistically.

Second, we should see our vision in a reasonable way – meaning, we need to understand the conditions and limitations that might exist now or in the future, and adjust our thoughts and actions accordingly.

We have to plan our steps based on what is possible, while still keeping our dreams alive.

And of course, resolving this conflict is different for everyone. For me it might be one way, for someone with less experience, another way, and for you, maybe in a completely different way. It depends on each person’s experiences and reflections.

Royesh: What would you compromise for your parents- and what would you not?

Fatima: I’m not willing to compromise my future for the sake of my parents. Because it’s me who will live in that future – not them. I know I can never truly repay the sacrifices my parents have made for me, but I want to say this honestly: I don’t want to give up my own future – the life in which I have to live and act – just because of the experiences my parents had in the past.

Royesh: Let me give you a few more practical examples from your own life – so we can see how you actually deal with these situations.

Your parents might have certain concerns: about the way you dress,

about where you go and how you spend your time outside, about when you come and go, about the people you interact with, or even about some of the activities and plans you have for your future – your dreams and ambitions.

In which of these areas are you willing to respect your parents’ wishes without feeling that it causes you any real conflict? And in which areas are you not willing to compromise – where you think your parents might be the ones who should adjust and understand you instead?

Fatima: When it comes to compromise with my parents, I’m willing to adjust when it comes to clothing. That’s something I can accept. But when it comes to connecting with society, I’m not willing to compromise.

For example, if they tell me, “You shouldn’t go to this place,” I wouldn’t agree – because the places I go to now…

Royesh: But what if those places are dangerous? What if there’s a real risk in going there? Then what would you do?

Fatima: If there’s really a danger, and I can feel that risk myself, then yes – I would compromise. But if I don’t personally sense any danger,

then no, I wouldn’t. And when it comes to my future – the decisions that belong to me – I’d say I compromise half and half: fifty percent yes, fifty percent no.

Royesh: The places you want to go, or the people you want to meet and connect with – how are these things so closely tied to your future that you’d be willing to risk losing your parents’ approval over them?

Fatima: It’s not about losing my parents, Ustad – I would never want to lose them.

Royesh: Your parents may feel hurt and say, “I feel scared.” They worry that if you spend time with those people or go to those places, real dangers could happen. They speak from their own experience – they’re afraid. If you ignore their concerns, you’ll upset them, and you risk losing them.

Fatima: Yes, Ustad – that’s true. But the places I go and the things I see there teach me lessons. Maybe later I’ll regret going, but even that regret will become an experience – something I can learn from.

Royesh: Sometimes, experience can be like drinking poison – if you drink it, you die. So how can someone share that experience afterward?

Is it really possible to say, “I’ll drink the poison just to see whether it kills or not”?

Fatima: Yes, Ustad – that side of it should also be taken into consideration.

Royesh: That’s exactly what I want to ask you. For example, there might be dreams you have that your parents easily agree with. So far, they haven’t created any problems with your education itself, but maybe they’ve had concerns about where you study.

They haven’t objected to your dream of becoming a leader, of growing as a confident and respected person – but they might have concerns about who you spend time with or when you go out.

So, if respecting these concerns would make your parents happy – and show them that you value their worries – wouldn’t that be easier than risking your whole plan for the future?

Fatima: Yes, Ustad – you’re right.

Royesh: So then, which things are you willing to compromise on with your parents – as part of an empowerment exercise – and which things are you not willing to compromise on?

Fatima: From an empowerment point of view, I choose to compromise with my parents – because forcing things or insisting on them never brings real results.

In leadership, we’ve learned that we can’t make others follow our decisions by force. So instead, we find another way – we look for different paths and solutions. And sometimes, through those new ways, we can still achieve what we truly want.

Royesh: Have you ever imagined reaching a point where, no matter what it costs, you might lose your parents’ approval – even if it means hurting or upsetting them?

Fatima: No, Ustad – never. Because my parents are my greatest supporters. And after what you just said, I won’t even let such a thought cross my mind. My parents are the biggest source of strength and the most precious part of my life.

Royesh: There’s really no reason for you to see your parents as enemies of your dreams. The challenges you face aren’t about the dreams themselves – they’re about how those dreams are put into practice, right?

That’s why, when it comes to how things are done, you need to find ways to compromise with your parents. And when your parents make compromises, it’s not about changing your dreams – it’s about adjusting how those dreams take shape.

So the easier path is this: you compromise in what they care about, and they compromise in what you care about.

That’s a beautiful example of an empowerment exercise. Anyway, let’s move forward.

Royesh: I read in your bio that you went to kindergarten when you were four years old – is that right?

Fatima: Yes, that’s right, Ustad.

Royesh: Tell me about your first days in kindergarten – being with other children for the first time, and being under the care and attention of a teacher. What do you remember from those early days? What feelings or memories come to mind?

Fatima: I don’t remember the very first day exactly, but the memories I have from kindergarten are really sweet. I remember one day when my friends and I built something using those colorful plastic blocks that kids usually play with. It turned out so beautiful! We ran to our teachers – we had two very kind teachers – and excitedly said, “Teacher, look! We made this!”

Another day, I remember spinning around while playing, and I spun so much that I fell to the ground and started crying. My teacher picked me up, hugged me, and comforted me.

There’s another beautiful memory – every day, our whole class would walk together with the teacher to a small shop nearby. We’d buy a box of biscuits and then all walk back together, laughing.

Kindergarten days really feel like the beginning of life. It’s like the moment when you first step into society – when you start dreaming, imagining your future, and enjoying those pure, happy moments with your very first teacher and your very first classmates.

Royesh: Do you still remember anyone from your kindergarten days – someone you became friends with back then and are still friends with today?

Fatima: I did have a close friend back then, but we’re not in touch anymore. He was my cousin – we were the same age, and we both went to kindergarten together. We used to play a lot, and that friendship continued until we were about six or seven years old. Now he lives in Iran as a refugee.

Back then, we also played with the girls from our neighborhood. Every afternoon, when we went outside, we’d all gather in an open space near our homes and play football together. Those were really happy, carefree days.

Royesh: I read something in your story about the “Barg” course. Can you tell me what that was? What kind of course was it – and what memories do you have from it?

Fatima: Ustad, the Barg course was something like a preschool – in Iran, they call it a stage of preparation before starting formal school. It was a bit more advanced than kindergarten; we studied school subjects there, but it wasn’t as serious or strict as a real school.

At Barg, we had a teacher named Ms. Khadija. There were many students – the classroom was always full. I used to go there with my neighbor, Fawzia, and we studied together up to grade five.

Later, our teacher told us, “You both are still too young – you can’t move on to grade six just yet.” So that’s how our time at Barg ended.

One funny memory I have from those days is about wintertime. When Fawzia and I used to walk to the Barg course, the roads were icy and slippery. Every time we stepped on the ground, we would slide and fall – sometimes I teased her, and sometimes she teased me back. I was the smallest among everyone, so they used to call me “Qadoogak” – little Fatima, the tiny one. That’s one of the sweetest and funniest memories I still remember from that time.

Royesh: Now, let’s go back to that time – to your childhood and your early school years. How did your parents support you during those days? What kind of care or encouragement did they give you?

Fatima: Ustad, I’ve always had my parents’ support. Back then, they encouraged me in every way – by enrolling me in kindergarten and the Barg course, by helping me with my lessons, and by providing everything I needed for school.

Their support came in many forms – sometimes openly, and sometimes quietly behind the scenes – but it was always there.

Royesh: Now, if you look at all that support as an example, can you really find a reason to say that your parents are against you now – especially in the things that help you grow and move forward?

Fatima: No, Ustad – not at all.

Royesh: Where did you study your primary school years?

Fatima: I studied my primary school years at Ustad Haji Mohammad Mohaqiq School.

Royesh: Do you mean Haji Mohammad Mohaqiq, the political leader?

Fatima: Yes, Ustad – the school carried his name, but I’m not sure if it actually belonged to him or if it was just named after him.

Royesh: Where was that school located? And what kinds of subjects did you study there?

Fatima: We studied the regular school subjects there. I joined directly in grade two, because I had already completed up to grade five at the Barg course.

The first classroom we studied in was actually the school’s kitchen – it was in the basement. They had covered the floor with a carpet and placed the blackboard in front of it.

Those days were so beautiful for me. Even now, when I remember them,

I find myself wishing I could go back. Because I truly feel that time was much more beautiful than the situation we have today.

Royesh: If you wanted to describe what made those days so beautiful – in the language of your childhood dreams – what were the wishes or dreams you had back in grades one, two, or three that made the world feel so lovely to you?

Fatima: The beauty of those childhood days was really in my friends and my teachers. There were three or four of us who were very close friends,

and we shared the most beautiful moments together. After school, during our sports hour, we all went near the mosque and played together until noon. When the mullah called the azan, we’d run back home.

During recess, we’d play with our teachers in the schoolyard, and on the days when it was our class’s turn to recite the national anthem or verses from the Holy Qur’an, we’d all get nervous, wondering who would sing the anthem.

I still remember one time – during the national anthem, I was standing at the back of the line, just moving my lips without singing, because I had completely forgotten the words!

The beauty of that time was in being together – learning, laughing, and growing side by side.

Royesh: If you think back to your teachers from primary school – who was the first teacher you truly loved the most? Can you tell us their name and explain what made you love them so much?

Fatima: I honestly loved all my teachers – because I have good memories with each of them. There was Ustad Abbas, who was very funny and playful; he used to play football with us.

Then there was Ustad Ghulam Reza, a serious teacher, but an excellent one – he taught us really well. Our school principal, Ustad Ghulam Ali, was also a wonderful person and played an important role in our learning and growth.

And one of my favorite teachers was Ms. Masoumeh, our math teacher.

She was so kind – every time she checked our homework, she would draw a little smiley face, a star, or a flower beside it.

We used to show our notebooks to each other and count how many stars or drawings we got. We’d say, “I got more stars than you!” and then we’d color the drawings and make them even prettier. Those little things made learning so joyful.

Royesh: Which subject did you enjoy the most during your primary school years – the one that felt sweetest and most enjoyable to you?

Fatima: I loved all the subjects, but as a child, I especially loved drawing. For anyone just starting school, drawing feels so beautiful –

and for me, it was the most exciting thing. Using my colorful pencils to bring the images from my mind onto paper was something that always made me happy.

Royesh: Now, if we take you back in time – to when you were in fifth grade, around eight or nine years old – what picture comes to your mind when you think of that Fatima? How do you see yourself at that age?

Fatima: When I was in fifth grade, I was a very playful girl. I always loved being at school – spending time with my friends and learning new things.

I was a curious girl, always wanting to explore and discover. Maybe I was a little lazy at home – because I hardly ever helped with house chores! I loved watching cartoons, playing games with my friends, discovering new games, reading poems, and drawing pictures. Those were the things that made me truly happy back then.

Royesh: Among your classmates from those years, who were the ones you loved the most – the friends you were closest to, the ones you laughed and played with more than anyone else?

Fatima: My friends at school and the ones in our neighborhood were a bit different. In the neighborhood where I played, we had a small, close community.

At school, two of my closest friends were Ruqia and Nargis, and later another girl joined us – Malika, who had just come from Pakistan. We spent our primary school years together, from grade one all the way to grades four and five.

Nargis and Ruqia are still my classmates in the Cluster program today. I really loved those girls – we were inseparable. Even in the evenings after prayer at the mosque, the three or four of us would gather. We’d finish our prayers quickly – even before the mullah – then sneak behind the mosque and play scary games together.

In our Qur’an course, we’d also sit together before class. Malika always knew spooky stories, and she would tell them to us while we closed the doors and windows, pretending we were trapped inside a haunted room.

In our neighborhood, I also had friends named Fawzia, Arifa, and Nazdana. Every afternoon, we went out and played – football, Wasinti, or any other games we could make up. Sometimes we stayed inside, watched cartoons, or played with my dolls. We built tiny houses out of pillows and imagined our own little world.

Those were such beautiful days, Ustad – truly the sweetest days of my childhood.

Royesh: During those childhood years, do you remember the first time you got sick – really sick – and realized that something was wrong? When was that?

Fatima: Ustad, at the beginning of my illness, I was such a carefree girl – I didn’t even think much about it. When it first started, it was just pain in my leg, and I didn’t take it seriously at all.

My father tried some home remedies, but they didn’t work. Then we went to a bone setter, and just one or two hours after we visited him, we heard that he had passed away.

After that, for about two months, we kept going to the public hospital for treatment. My mother still remembers that the doctor gave me some colorful pills – two-toned – but even then, I wasn’t too concerned.

Gradually, though, it got worse – to the point where I couldn’t even walk anymore. It happened near the end of the school term, just as winter was beginning. That’s when the hardest period of my life slowly began.

Royesh: What grade were you in at that time?

Fatima: Ustad, I had just finished grade five – it was during the winter break.

Royesh: When the pain in your legs or bones first started bothering you badly, what did you tell your friends about it? How did you talk about that pain with them?

Fatima: Ustad, I don’t think I was in touch with my friends much at that time, because I was mostly staying at home. But I still clearly remember one particular day – it was winter, raining heavily, and the streets were muddy. I was attending an English course called Goharshad, and even though my leg hurt, I still went. On the way back, my mother came halfway to meet me and helped me walk home through the mud.

I didn’t really talk to my friends about the pain. I’ve always been the kind of person who keeps things to herself and tries to deal with everything quietly, on my own.

Royesh: So, you used to bear the pain all by yourself?

Fatima: Yes, Ustad. Sometimes I would complain and say, “Mother, my leg hurts…” but my mother would tell me, “It’s okay, be patient.”

She was already working so hard, and since visiting doctors, bone setters, and healers hadn’t helped at all, I decided not to say much anymore. I just kept the pain to myself and tried to endure it.

Royesh: If you look back and compare your parents’ reactions – as a memory – which one of them did you feel was closer to you in those painful moments? Who did truly feel your pain and shared it with you as if it were their own?

Fatima: Ustad, both of them shared my pain – but my mother showed it more openly, while my father expressed it less. He’s a quiet and calm person, someone who keeps his feelings inside and doesn’t show much on the surface. But I could feel it – I knew both of them were hurting with me.

At night, around ten or eleven, I couldn’t fall asleep anymore. I stayed awake from midnight until morning, and through all those long nights, I knew my parents were suffering right beside me.

Royesh: When was it – and which doctor told you – that your illness might be serious and that you needed to go to Pakistan for treatment? And when you first heard those words, what did you feel inside?

Fatima: It was Dr. Zia Elham, an orthopedic specialist in Mazar. When we went to see him, the waiting hall was crowded with patients. We waited for almost three hours before it was finally our turn. He told us to go to Mawlawi Hospital to get an MRI scan. I still remember that day very clearly – the MRI room was freezing cold, and the doctor told me,

“You must not move for a full hour.”

By then it was already dark, almost night. My parents were standing nearby, talking to each other from time to time just to distract me – so I wouldn’t move and ruin the image.

Two days later, my father went back to get the results. The doctor told him, “Yes, this is cancer. You either have to go to the French hospital in Kabul – which is expensive – or you should go to Pakistan for treatment.”

After that, my mother and father talked it over and decided that we would go to Pakistan.

As for me, I don’t remember having much of a reaction. By then, I had already been suffering from pain for so long that the news didn’t really affect me. It just didn’t seem to matter anymore.

Royesh: The word cancer itself is frightening – anywhere in the world, but especially in Afghanistan. When your family heard it – your father, your mother, and even you – did that fear take hold of you? Did you all feel scared hearing that word?

Fatima: Ustad, that was the first time I had ever heard the word cancer – or even tumor.

Before that, I didn’t know anything about them. Yes, for my family it was very worrying. They had heard that cancer is a deadly disease, and the doctor also asked if anyone in our relatives had ever suffered from it.

My parents remembered that one of their distant relatives had once died from a kind of swelling, and they thought maybe that had also been cancer. The doctor said that cancer can sometimes be hereditary, that it can pass through families – not necessarily close relatives, but even distant ones.

For me, it was also a little frightening, but since I didn’t really understand what it was, I wasn’t deeply afraid – I just took it lightly, almost carelessly.

Royesh: Tell me a little about the pain itself – before you went to Pakistan. What did you feel then? Was the pain very strong? How much were you suffering at that time?

Fatima: Yes, Ustad – the pain was truly unbearable. But more than the physical pain that I felt, what hurt me most was seeing my family suffer because of it. I started to feel like a burden to them. Not being able to walk, not being able to move on my own – that was the hardest part of all. That feeling was even more painful than the illness itself.

Royesh: Tell me about your first journey to Pakistan with your father. How did it all happen? What made you finally decide – and feel determined – that you had to go to Pakistan for treatment?

Fatima: After we had tried every possible treatment in Mazar, my parents decided it wasn’t worth spending more time in Kabul. They said, “If we go there and still don’t get results, it will only waste time and cause more pain.” So, we chose to go to Pakistan instead.

My parents and I traveled to Kabul first. We stayed there for about one or two weeks to get our passports and the visa for Pakistan. At that time, getting a Pakistani visa was really difficult, so we had to go through a broker. My father paid for it.

I still remember – my father even went to see Mohammad Mohaqiq

to ask for help. It was raining in Kabul, and the streets were muddy.

My father, with mud-covered shoes, went to the place where Mohaqiq was staying. But the guards at the gate didn’t treat him well. They looked at him in a humiliating way.

That moment was very painful for me – seeing my father, a man of dignity, standing there being looked down upon by strangers. He had never faced such a situation before, and watching him be treated that way broke my heart.

Fatima: After my father and I finally got the visa, we started our journey toward Jalalabad – that was the beginning of our trip. From there, we continued on to Peshawar. In Peshawar, we met a translator who helped us find another doctor. He took us to see him for further checkups and advice, and that’s how the next chapter of my treatment began.

Royesh: Before you went to Peshawar – you mentioned that a broker helped you get the visa. How much did it cost your family to get that visa?

Fatima: I don’t remember exactly how much it cost, but as far as I can recall, Mohaqiq had some connections. When my father went to see him, he made a phone call and said, “Please issue this person’s visa.”

After that, we received the visa and began our journey to Pakistan.

Royesh: When you arrived in Pakistan, did you go straight to Shaukat Khanum Hospital, or did you first stay in Peshawar for a while?

Fatima: No, Ustad – first we went to Peshawar. We had somehow met a translator there, and through him we went to a local hospital. The doctor there said he could perform the surgery right away. He asked for around 25,000 rupees, maybe even more, and said, “I’ll operate immediately – but without any diagnosis, without any tests. Whatever happens afterward will be your own responsibility.”

When my father asked around and got some advice, he decided against it. People told him there was a hospital in Lahore called Shaukat Khanum. They said it was founded by Imran Khan, named after his mother, Shaukat Khanum, who had died of cancer.

That hospital also had branches in Peshawar, Quetta, and Karachi, but the main center was in Lahore. So my father decided we should go there for proper treatment – and that’s how we ended up in Lahore.

Royesh: When you arrived at Shaukat Khanum Hospital, what were the things that caught your attention the most – as a curious young girl who had come there for treatment? What seemed new, strange, or surprising to you in that environment?

Fatima: What really surprised me at first, even before we reached the hospital, were the people. You know how, when you watch Indian or Pakistani movies, you imagine everyone looking a certain way – darker-skinned, different from us – it all felt strange and new to me. When I saw them in real life, it felt like I was inside a movie – watching it unfold around me.

There were people from every background – some poor, some wealthy – and you could sense that just by looking at them. The language was new to me too, and the weather was extremely hot – that was another shock.

At Shaukat Khanum Hospital, what amazed me most was the kindness of the people. The doctors there were so polite and responsible – very different from what I had seen in Afghanistan. The Afghan doctors I’d met were often serious or impatient, but in Pakistan, they treated patients with such warmth and respect. I remember how, while I was hospitalized, different people would come and play with the children,

bring us small gifts, and take pictures with us. It really lifted our spirits.

There was also a special room in the hospital just for children – filled with toys, games, and a television – so that kids could play and forget their pain for a while. That place felt completely new and wonderful to me.

Royesh: At Shaukat Khanum Hospital, you must have seen many children and people – all of them suffering from cancer, just like you. When you saw so many others sharing the same pain, did it bring you any sense of comfort – knowing you weren’t alone? Or did it make your pain even heavier, feeling the weight of all that suffering around you?

Fatima: Ustad, feeling empathy for people who suffer the same pain as you can be both comforting and painful – but for me, it was mostly painful. Watching others in pain was hard for me; it made my heart ache even more.

At the hospital, there were all kinds of people – children and adults, men and women, young and old – and all of them had cancer.

Some had it in their shoulders, some in their necks, many women had breast cancer, young people like me mostly had bone cancer, and the children often had blood cancer.

What struck me most was how similar we all looked – none of us had hair. That was the one thing that made us alike, and in a strange way, it helped us understand each other’s pain. It was both sad and, in some way, fascinating.

In the first two months, while my father and I stayed for tests, we lived in a small area near the hospital where most of the residents were Afghans – people from Herat and other provinces: Pashtuns, Hazaras, Tajiks, Uzbeks – all living together.

But the place wasn’t suitable for patients. The rent was cheap, and that’s why many families stayed there, but it was right next to a cowshed. The smell, the flies, the atmosphere – it was terrible for someone sick like me.

Also, the weather there wasn’t good – it was hot and humid, and the air felt heavy. The surrounding areas were a bit better, but where we stayed, most of the rooms weren’t in good condition. They didn’t have proper facilities or clean bathrooms, and that made life even harder for the patients staying there.

After about two months, when my mother came to join us, we decided to move to a better place.

Royesh: When you arrived there, did the doctors start your treatment all over again from the beginning, or did they rely on the medical reports and treatments you had already received in Afghanistan – in Kabul and other places – to confirm your diagnosis?

Fatima: All the treatments and tests were started again from the beginning. During the first two months after my father and I arrived, we were helped by a translator – Ali – the son of one of our acquaintances who was studying in Lahore. He stayed with us for a long time and translated everything.

For about two months, I went through every possible test – CT scans, MRIs, and many other examinations. At one point, the Mohammad Ali Jinnah Hospital in Lahore even took a biopsy from my knee, and I was hospitalized there for a week.

During that time, I met many different people with all kinds of illnesses.

After two months, my treatment finally began. Ali told us that the Shaukat Khanum Hospital offers free treatment for patients who can’t afford it. So, with his help, my father spoke to the hospital administration and explained our financial situation.

After that conversation, all my treatments became completely free. But the first two months – all the tests and checkups – were paid for by us.

Royesh: Tell us about the hardest days of your chemotherapy. For people with cancer, going through continuous chemotherapy sessions

is often the most painful and difficult part of treatment. What was your experience like during those days?

Fatima: Before that, I didn’t really know what chemotherapy was – but my first experience with it was truly, truly difficult. The medicine itself, the chemo liquid, has a color that already makes you feel sick – a yellowish-red that gives you a strange feeling of disgust even before it enters your body.

When they inject it, you feel a deep weakness spreading through you. Your mouth burns as if it’s been scalded, you can’t speak properly, and you feel exhausted to your bones.

Then your hair starts falling out – and later your eyelashes and eyebrows, too. I went through all of that. You lose your appetite; even the smell of food makes you sick. And in Pakistan, the food was already spicy – the bread wasn’t like the soft Afghan naan we were used to.

Everything felt bitter and heavy.

I still remember one day very clearly: my father came to me and said gently, “Come, eat something.” But I couldn’t bear it. I pretended to faint – I closed my eyes and didn’t move, because even the thought of food made me nauseous.

And chemo isn’t just one injection – during a single week in the hospital,

you have around 15 to 20 IV drips, plus countless injections, syrups, and pills. It’s not only your body that suffers – your soul gets tired, too.

Royesh: As a girl around ten or eleven years old, when you suddenly saw your hair and eyebrows falling out and your whole face and head completely changing – what did you feel in that moment? What pain and suffering were you experiencing?

Fatema: Ustad, for a girl, the most important thing is her hair. During those days when I was going through chemotherapy, every time I touched my head, handfuls of hair would fall out. Soon after that, I no longer had eyelashes or eyebrows either – it was as if I didn’t even remember what it meant to have hair anymore.

Then came an even harder moment. The doctor had told us that after starting treatment, the patient shouldn’t be kept far from the hospital. When my parents talked about it, my father said, “If I stay here for a whole year, I might lose my job and won’t be able to support the family.”

So my mother decided to come and take his place. She came to Pakistan, and my father returned to Kabul. After my first round of chemotherapy, my father and I decided to go back to Kabul for a short time.

We stayed at a friend’s house there, and that’s where my mother came to meet us.

I still remember that day – the first time she held me in her arms again.

She brought me a small doll as a gift. My brother came along with one of the neighbors, pretending to be his nephew. And that day, in that house, my mother shaved my head completely – every single strand of hair was gone. It’s really hard for a girl to lose her hair. It was very painful – every time I laid my head on the pillow, a large bunch of my hair would fall out. When I looked into the mirror, it didn’t feel good at all – seeing myself with no hair, no eyelashes, and no eyebrows.

Royesh: In those days, with all the hardship and the struggle to keep living, what kept you hopeful?

Fatima: My family. Seeing them and being with them always gave me a good feeling. I kept wishing that after all this pain, I could have happy moments with them again.

Royesh: What in Pakistan felt inspiring or educational to you?

Fatima: Sir, as I said, people’s kindness really inspired me. No one interfered in others’ lives-whether you were Muslim or Christian, wore hijab or not, how you ate or didn’t eat. That openness affected me. In Ramadan, people ate freely in restaurants; women wore what they liked; people went out whenever they wanted; girls could go out when they wished. That was beautiful to me. Experiencing that in my own country-where I grew up-still feels like a dream I hope to reach.

Royesh: During treatment, did doctors ever say your knees or legs had to be operated on?

Fatima: Yes, sir. After 7 or 8 rounds of chemo, the orthopedic doctor-Dr. Ilyas-said the bone cancer had decreased to 10%. If, after two or three more rounds, it went down to 2%, they would just shave the knee and it would be fine. But if it only went to 7%, they’d have to operate. After more chemo, tests showed it at 7%, not 2%. They said, “Either we operate, or if you refuse, whatever happens is no longer our responsibility. If we operate, you can come to Shaukat Khanum for life with any issues.”

The day they said my leg had to be amputated was very hard. They offered two options: remove just the knee and reattach the lower leg that was healthy, or remove everything below the knee.

And in that moment, making a decision was truly difficult- it felt like choosing between living and really living, between a slow death and a life that still had meaning. It was one of the hardest decisions of my life, and I remember that day so clearly.

I remember crying in the waiting hall with my mother and a translator, saying, “What kind of life is it if I can’t run, play with my friends, or even walk? I don’t want that life.” I was very hopeless. My mother comforted me, reminding me that many in Afghanistan have been injured in blasts and still live their lives. She comforted me, but no one was there to comfort her. It was a very hard decision.

Royesh: And the cancer was specifically in the knee?

Fatima: Yes, sir-right in the knee joint. After the chemotherapy and surgery, the doctors said they would remove my knee and reattach the lower part of my leg-but in reverse-so that later, when I grew up, the ankle joint could function in place of the knee. They said that eventually, I could be fitted with an artificial leg.

They even showed us a video of another girl who had undergone the same kind of surgery. She had grown up and, with her artificial leg, could walk, play, run, even play football-living her life quite normally.

Another thing was that the surgery they performed on me was the first of its kind at Shaukat Khanum Hospital. The doctors were anxious, and I was too. We were all wondering whether the operation would succeed-whether it would really work or not.

A day before the surgery, the doctors told me, “Tomorrow is your turn.”

They admitted me that day, ran the final tests, and prepared everything.

At 7 a.m. I was taken into the operating room, and it wasn’t until around 9 p.m. that the surgery ended. As far as I remember, when I entered the operating room, I was completely alone-only the translator was with me. My mother was waiting outside, all by herself. I still can’t imagine what she must have felt at that moment-or even what I truly felt myself. It was one of the hardest moments of my life.

When the doctor inserted a long needle into my lower back for the spinal injection, the pain was unbearable. I cried a lot. The doctor said, “If you don’t stop crying, I won’t be able to operate.”

After they injected the anesthesia, my eyes closed-and I remember nothing else.

The surgery lasted 12 or 13 hours-one of the longest and hardest operations ever done in that hospital. When I finally opened my eyes, my whole body felt frozen. I couldn’t feel anything-not even my legs. My mother was beside me, and I told her, “I feel cold… my legs are freezing.”

Later, when they moved me to a normal room, my surgeon came in the next morning. He said, “Move your leg.” I moved it slightly. He smiled-and from that smile, I understood that the surgery had been a success. Then he quietly left the room.

What I found most remarkable was the kindness and warmth of the doctors who treated me. During that time, I had two main doctors-Dr. Rabia and Dr. Elias-and another female doctor whose name I can’t quite remember now. They were all very caring and supportive throughout my treatment.

Since I knew a little English, I would sometimes speak in Urdu and sometimes in English, creating a funny mix of languages. For important appointments, we went with a translator; but for the simpler meetings-like when the doctors advised what food I should eat-my mother and I managed on our own.

Sometimes, truly strange situations would happen. Once, we couldn’t find a translator at all. It was really hard because there were so many Afghan patients, and hiring a translator cost a lot of money. So, during one appointment, our conversation turned into a chain of languages:

My mother spoke Farsi, another woman translated it into Pashto (she knew both Farsi and Pashto), then a Pakistani lady translated that Pashto into Urdu for the doctor.

It was like a beautiful display of teamwork through languages-a living example of how people can still understand each other, even across barriers. Moments like that made my experience there strangely fascinating and memorable.

Royesh: After surgery, when you woke up, what was the first word or moment that gave you hope-that brought back your sense of being a girl again?

Fatema: “The phrase ‘the dream of being a girl after surgery’ sounds really interesting, Ustad!

When I first opened my eyes, all I could see was the hospital hall – a large recovery room filled with other patients like me, lying quietly in their beds after surgery. Everyone seemed exhausted, pale, and silent.

At that moment, my only dream wasn’t about beauty, school, or my hair – it was simply to leave the hospital. I longed to step outside, to feel fresh air again, to walk under the open sky. I was so tired of the smell of medicines, the sight of IV tubes and bandages, and the endless silence of that place.

My only wish was to see my family again – to sit with them, talk to them, and laugh like before.

Each week of chemotherapy felt endlessly difficult. You couldn’t go outside – not even step out of your room. The smell of the medicines filled the air, thick and heavy. You saw patients in pain, each carrying their own silent story. The food tasted so bitter and lifeless that even a single bite felt like a burden.

Everything around you – the smell, the sounds, the silence – reminded you that you were fighting for life. Enduring all of that, even for just one week, was painfully hard.

Royesh: Usually there’s a sweet line that marks the end of a painful struggle-the beginning of a new chapter-the “You won!” moment. Did your doctors ever say, “Fatima, you’ve beaten cancer; you’re fully recovered”? When did you truly feel that joy?

Fatema: “Ustad, my story doesn’t end so quickly – half of it was still ahead of me. Even after the surgery, the doctors said that to be completely sure no cancer cells were left, I needed to go through two more rounds of chemotherapy. Those two sessions were the hardest of all. They weakened my heart so much that it was working at only 20 percent of its normal capacity. I was literally standing on the thin line between life and death.

Even now, after all these years, my heart functions only about 40 to 45 percent. I’m still alive because of the medicines I take every single day. If I ever stop taking them, maybe… maybe you would never see Fatema again.

During that time, I continued my treatments – not for cancer anymore, but for my heart. And finally, one day, the doctors told us, ‘There’s no more sign of cancer. You can go home.’

That moment was indescribable. I turned to my mother and said, ‘What a beautiful moment – I’m finally going back home.’ It felt like the world had opened up again – like I was being given a second chance at life.”

During our time in Pakistan, my father would visit occasionally – once or twice. One time, he even brought my little sister with him. When we first went to Pakistan, she was very young, and my mother had to leave her at home. My older sister made a huge sacrifice during that time.

She couldn’t continue her university studies properly – it was the very year she was supposed to take the Kankor (university entrance exam). Her dream was to study Computer Science, but because of the heavy responsibilities that suddenly fell on her shoulders, she couldn’t pursue it. She became like a mother at home – taking care of my younger sisters, managing the house, being active in the community, and still trying to keep up with her studies.

When the final days in Pakistan came, both my parents came together, and the three of us – my mother, my father, and I – returned to Afghanistan.

The moment I crossed the border was unforgettable. I felt something deep and sacred – a sense of returning home, of belonging. I wanted to kneel down and kiss the ground of my homeland. I wanted to touch the soil of my homeland – to feel it with my hands.

It was a feeling like pure love for one’s country, a deep sense of belonging that only those who have been away from home for a long time can truly understand,

Royesh: For Fatima, returning to Afghanistan wasn’t just a return home-it was a return to life: to 6th grade, to the arms of friends and family, to everything. Above all, a return to life. How would you describe that feeling?

Fatima: Returning to my country, to my family’s embrace, to the house where I grew up with so many memories, to the neighborhood where I knew people-that felt beautiful.

When I got home, relatives, neighbors, and friends came to visit. My classmate Ruqia-my closest friend-came too. Seeing everyone again after so long felt wonderful. I had missed it so much.

My sister and I are two years apart and we always argued at home. When she called me in Pakistan, I’d say, “I even miss our little fights! I can’t wait to sit with you and argue again.” Coming back to our yard, breathing our neighborhood’s air-it felt like being born again.

Royesh: They often say that returning from a journey and returning from a war are two of life’s most transformative experiences – they change the way a person sees everything. You, Fatema, have returned from both – from a long journey and from a battle, a battle against a dangerous disease, a silent but deadly enemy.

When you came back this time – when you looked again at Mazar, at the streets where you grew up, your school, your teachers, your lessons – what felt different to you? What new emotions did this return awaken in you?

Fatema: What changed the most in my life was myself. And, of course, my classmates, since I was now in a new class and meeting new people. My personality had changed – I was no longer the same girl I used to be. Seeing my sisters gro wn up – seeing my older sister after a whole year, and my little sister, who was now taller and more mature – that touched me deeply.

The same sister I used to argue with all the time – now she, too, had changed. When I saw my father again, my neighbors, the familiar faces of my community – nothing around me had really changed much.

Everything was the same. But I was different. I had come back as a new person, someone shaped by new experiences.

Royesh: And what challenge faced you after coming back?

Fatima: The big challenge was bringing a new self into my old community and places. After such a hard experience, you become different. I had seen and experienced things far beyond what anyone in my neighborhood or school could imagine. That was my new challenge – to return to the same place, but as a different person.

When I joined the new class – grade six – I didn’t know anyone at first. It felt strange to sit among unfamiliar faces, to start all over again. But soon, I found new friends, kind ones who welcomed me.

By the time we reached grade eight, before the Taliban came, we had formed a small group of ten girls. We were more active, more alive, and much more spirited than in our childhood days.

Royesh: You said hair is very important for a girl. You returned with no hair. How did you handle that among friends?

Fatima: I tried to keep my scarf tight on my head. And my hair – I still remember it so clearly – it was so beautiful. I had curly black hair, and after every round of chemotherapy, when tiny strands began to grow again, I felt such joy – like a small sign of hope returning.

But then, when another round of chemo came, it would all fall out again… and I’d feel that sadness all over.

After I came back home, my hair slowly started to grow – my lashes came back, my eyebrows too. For a while, I had what I called “boyish hair” – short and uneven, like a little boy’s.

Every time my mother saw it, she would smile with such happiness. And each time I looked in the mirror, I’d say, “Mom, look – my hair’s longer than it was yesterday!”

That phase – when my hair was short and patchy, yet full of life – was actually beautiful to me. But brushing it, tying it, managing it every day – that was a real challenge I faced with both patience and pride.

Royesh: Did the doctors reassure you your hair would grow back?

Fatima: Yes, sir. They told me it would fall out and it would come back. It wouldn’t be permanent.

Royesh: When you returned, which teacher or friend encouraged you most?

Fatima: Teachers and classmates didn’t have the main role-my parents did. At first, I felt like a stranger in society; living in a changed body is hard. Still, my mother enrolled me in 6th grade. It was tough, but I adapted.

Royesh: After such a difficult illness, what did studying mean to you?

Fatima: Studying meant building a better future-the hope my parents gave me, the dream they had for me. My mother always said, “You should become a doctor so you can treat people who suffer the way you did.” I wanted to be someone who could help others out of that pain.

Royesh: You had barely recovered from your first pain – that enormous struggle for life – when the Taliban came, the schools were shut down, and once again you were faced with an even heavier pain:

the pain of being a girl in a society that fights against its daughters, that resists women. This time, what did you feel?

Fatema: Ustad, I can say this feeling was one of the hardest experiences of my entire life. It was only a year or two after I had returned from Pakistan – when I thought God had said, “You’ve suffered enough.”

But then it was as if He said again, “No, it’s time for another trial,” and He sent the Taliban into our lives.

Fortunately, in Mazar we were able to study for about a year longer than the girls in other provinces, and I managed to continue until grade 8. When I first came back from Pakistan, I studied grade 6 at Mohqiq School, and for grade 7, I joined Ali Abad High School – one of those schools where you could truly feel diversity: students from different neighborhoods, new faces, new teachers who had never met you before, and so many new and interesting subjects.

But when the Taliban came, all those beautiful moments I had at that school – all of them – were destroyed. I still remember the last days of our final exams. Our teacher came and said, “Today you must take all your exams – all subjects – because the Taliban might arrive any day now.”

So we did. That day became the last day I ever sat in a classroom, the last time I was with my classmates, the last time I saw my teachers. When we finished and stepped out of the classroom, I was… speechless. I walked to the school wall, placed my lips on it, and kissed it.

I looked back at my classroom – I could still see it from where I stood –

and I kissed that wall as if it were something sacred. Because for me, that school was holy ground – a place where I had learned knowledge,

where I had shared knowledge, and where I had grown.

That was the hardest goodbye of my life.

Royesh: You were among the fortunate ones – not long after the schools were shut down, the Cluster Education program began, and you joined it. Tell us about that experience: How did you first hear about Cluster Education, and what was it like on your first day entering the classroom? What memory from that day still stays with you?

Fatema: I first got to know Cluster Education when I was in grade 7. Some of my classmates were already attending Cluster, and I used to notice how quickly they answered the teachers’ questions at school – it really impressed me! I became curious and excited to join too.

My mother eventually enrolled me, and that’s how my journey with Cluster began. At that time, I was managing three different classes in one day – I attended Cluster at noon, then went to school in the afternoon, and in the evening I took my English course.

It was a busy schedule, but discovering Cluster became one of the best and most beautiful events of my life.

Royesh: What drew you most to Cluster?

Fatema: Ustad, what fascinated me most about Cluster Education was the diversity – the atmosphere, the people, and especially the class called Empowerment. I truly love that class.

When I first joined Cluster, our English teacher was Ustad Hassan. He taught us English, and that’s one of my earliest memories from those first days.

Gradually, after taking the placement exam, I was placed in Class A, the advanced level – and I’m still in that class today. Joining the Empowerment sessions changed everything for me. There, I discovered my true self – I found the power hidden within me, and I learned to see my life from a completely new perspective.

Royesh: For someone who had already felt inner strength through a unique life experience, what was new about “empowerment”?

Fatema: Ustad, what was new for me in Empowerment was the clarity it gave to my path. Maybe I had been strong before, but my dream wasn’t clear – I didn’t really know what it was or how to reach it. I couldn’t define a strategy or set goals for it. But in Empowerment, I finally learned how to see my dream clearly, to give it shape and direction, and to work hard toward making it real.

Royesh: You are among those who have had some of the most successful teamwork experiences in your Empowerment activities. In particular, your team – Team Khorsheed (Sunrise) – has been known as one of the most active and effective groups.

Tell us about your team. What kinds of things do you do together? How did the idea of forming this team come to your mind in the first place? And what kinds of programs or projects are you working on now as a team?

Fatema: Let me first introduce my team. I am the team leader, and our group has six members: Fawzia Erfani, Nazdana Ahmadi, Benin Jafari, Nazgol Hosseini, and Suraya Sadat – together, we make up a team of six.

The idea of forming this team actually came from your words, Ustad. You always encouraged us in every session to create teams, to work together, and to grow through cooperation.

At first, our group wasn’t official – it just started as a small initiative. But after about seven or eight months, we wrote our constitution and commitment letter, and each of us signed and placed our fingerprints on it.

Since then, we have continued working according to the rules and principles we set together as a team. The main activity we started with was teaching young girls English. After that, we gradually expanded to include other kinds of lessons and training as well.

Royesh: You chose a very beautiful and meaningful symbol for your team – the bird! Why did you choose this symbol? What message or idea did you want to express through the image of a bird?

Fatema: A bird represents someone who can fly freely – toward her dreams, toward the destination she chooses, without any barriers holding her back.

Even if the sky turns stormy, even if there’s thunder and lightning, she still finds new strategies and new paths to continue her flight through those challenges.

That’s what the bird means to us – freedom, resilience, and hope.

Royesh: I’ve heard that among all your team activities, the hugging exercise was one of the most exciting ones for you – when you and your teammates hugged each other. Why was it so special? Did it, in any way, connect to your experience of illness and what you went through back then?

Fatema: It didn’t really have any direct connection to my illness. It was simply an idea we created together as a team.

One day, I told my teammates: “Let’s all set an alarm on our phones – one specific time – and whenever the alarm rings, that’s the moment we all hug each other.”

We made it a rule: when the alarm goes off, no matter where we are, we have to hug.

And if we were alone and not together, then we had to hug ourselves.

It was honestly the most beautiful activity I’ve ever experienced. I still remember the first time – we were in class, the alarm rang, I asked the teacher for permission, went outside with Nazdana, and we hugged each other. It felt so beautiful.

For me, that hug meant sharing good energy – the good feeling I had, I passed to my friend; and the good feeling she had, she shared with me.

It was like transferring love, hope, and joy through a simple embrace.

Royesh: In teamwork, there are always moments that stay in our memory – beautiful stories, shared experiences, images, or feelings we take from working together.

As the team leader of Sunrise, you’ve surely had many such moments with your teammates – from books you’ve read together, to films you’ve watched, or projects you’ve completed side by side.

Which of these moments has been the most inspiring for you? Which memory or shared experience stands out most vividly in your heart?

Fatema: One of the most inspiring activities for me was our celebration of International Women’s Day (March 8). It was a day when everyone participated – our team members, our students, and even our mothers.

We invited the mothers of our students and also women from our neighborhood to join us. Each of us gave a flower to our students, and the students, in turn, gave those flowers to their mothers.

That moment was truly beautiful and emotional – many people were in tears. All the mothers thanked us for remembering and honoring them, for recognizing their presence and value.

They said, “Thank you for your effort, for teaching our children, and for reminding us that we matter.”

It was a moment of connection, gratitude, and empowerment – one that I will never forget.

Another activity that was deeply inspiring for me was our book distribution project. It was such a beautiful and meaningful experience.

We collected money together as a team, and one day we went to the schools to buy and distribute books. It was actually my first time going to the city without any adults – no parents, no teachers – only with my friends.

We bought 60 books, and when we paid, the bookseller said, “Your money is all in small notes.” I smiled and replied, “Yes, because your books are small too.” That moment felt so poetic to me – so simple yet powerful.

When we brought the books and distributed them among students in grades two and three, it was pure joy. The children opened the books immediately and started reading. They showed each other their covers and titles, saying, “Look! What’s the name of your book?”

When we finished and said, “Goodbye, students,” they all replied together, “Goodbye, teacher!”

That moment was truly heart-warming – seeing the sparkle of excitement in their eyes, the happiness of discovery, and knowing that we had somehow shared the gift of learning.

Even though we didn’t know each other personally, that connection through books felt magical.

Royesh: The true meaning of empowerment – as you’ve beautifully shown through your life – is realized when it becomes leadership, when you begin to lead.

You can only truly say “I am empowered” when you are able to lead – and in your case, this leadership is female leadership, girl leadership.

But right now, in our society, the image of a woman is often the image of total helplessness – to the point that people tell girls, “Don’t leave the house, or a wolf will eat you.” They say, “Don’t raise your voice – something terrible might happen.”

So here we have two extremes: On one side, a woman seen as completely powerless, and on the other, a leader with full strength and influence, someone whose words and actions shape change.

Between these two – between this weakness and that power – there’s a long, difficult journey. And you, Fatema, have already walked that journey once – between life and death, between pain and survival.

Now, after all that, do you feel that this path – this struggle – has made you more hopeful about leadership? Do you see yourself now as a capable, strong leader?

Fatema: Absolutely, Ustad. The journey I’ve been through has played a very important role in shaping the kind of leader I am today – and the kind of leader I hope to become in the future.

When a person discovers the power and strength within themselves, a natural desire is born – the desire to share it with others. And that, for me, is leadership: to share the knowledge and awareness I’ve gained,

to help my teammates and those around me benefit from what I’ve learned, and to make my own growth meaningful by turning it into a source of empowerment for others.

“Female leadership” is such a beautiful phrase. For me, it means a society free from discrimination – free from racism, sexism, ethnic or religious bias, and even prejudice based on the color of one’s skin.

Like Martin Luther King once said, “I have a dream,” I too have a dream – I have a dream that in my society, no one will ever suffer because of their gender, their nationality, their religion, or their identity.

My dream of female leadership is a leadership where people are judged by their abilities and merit, not by whether they are men or women – not by their ethnicity, tribe, or faith. Where no one says, “You are Hazara, Tajik, Pashtun, Uzbek, Hindu, or Muslim – Shia or Sunni.”

In my view, female leadership carries the spirit of motherhood – the way a mother loves all her children equally. She doesn’t say, “You listen to me more, so I love you more,” or “You disobey me, so I love you less.”

A mother’s love is equal, fair, and unconditional – and that is how I see the true essence of female leadership: leadership born from love, fairness, and empathy, not power, ego, or domination.

Royesh: Leadership, in empowerment, usually begins from the closest circle – from those right around us. When a person feels empowered, sharing that empowerment is itself an act of leadership. So, if you were to reflect your leadership back toward your parents – the people who played the greatest role in empowering you – as a gesture of gratitude (you received strength, and now you give strength back), what would you say to them? What message would you, as a leader, give to your father and mother?

Fatema: My message to my parents, as a leader, is one of deep gratitude. I am truly thankful to them for standing beside me through every difficult moment of my life – for supporting me when I was at my weakest, for carrying my pain as if it were their own.

They endured hardships, yet they put my comfort before theirs. There were days when they needed support, but instead, they supported me. There were moments when my mother herself was fragile, yet she made me stronger. I am who I am today because of them – because of their patience, their love, and their unwavering faith in me. Even when life has been hardest, they have never stopped believing in me, and for that, I will always be thankful.

Royesh: If you wanted to send a message – not to a person, but to life itself – what would you say? What would be your message to life?

Fatema: I would say to life – you may bring me thousands of challenges, but I am that strong Fatema whom no trial can bring down. You might exhaust me, but every time I remember my dream, I find my strength and motivation again.

Maybe one day you’ll give me illness again, maybe the Taliban will rule for a long time, or perhaps there will come another government with new barriers – but my dream stands higher than every obstacle you place before me.

Royesh: With the tone you take, Fatema, do you feel that life is your rival – something that tries to defeat you and bring you down? Or do you see life as your friend – something you still love despite the pain it gives?

Because from the way you speak, it sounds like you love life deeply, yet in your words, there’s also a small trace of hurt – as if somewhere inside, you still feel that life has been unfair to you, that it keeps testing and tormenting you. Is that true?

Fatema: Yes, Ustad… life can be painful at times – and at other times, so beautifully sweet. There are moments of love, friendship, and joy that make you hopeful again, and then there are moments of hardship that make you want to turn away from life.

I think everyone goes through both – we all have. We may carry some bitterness in our hearts, yet still hold beautiful hopes for life. Sometimes, when I sit quietly and speak to myself, I tell God: “You are being unfair.

If You wanted to give me cancer, at least You could have made me born in another country where I could study more, or if You were to give me cancer, at least don’t bring the Taliban – so I could continue my education.”

So yes – I may sometimes resent life, but at the same time, I’m also grateful for it.

Royesh: The paradox of love and hate!

Fatima: Yes.

Royesh: Between this love and this anger toward life, which one weighs more in your heart? Do you truly love life, or do you secretly resent it – feel tired of its trials, and wish to turn your back on it?

Fatima: I love life more than I hate it. I have a dream and I want to live it-I don’t want life to end.

Royesh: You don’t want to lose life. Do you?

Fatema: No – I don’t want to lose life. Because I still want to reach the dream I have… or maybe even go beyond it. I don’t want to give up on living. I want to experience the beautiful moments that life still holds for me.

Royesh: Thank you, dear Fatema. I know I troubled you more than usual today – I wanted to revisit the painful parts of your story, but to hear them through the sweetness of your words, the beauty of your struggle, and the victory you have created out of your pain.

That’s what gives hope – not just to me, but to everyone who will hear you. You know, when we love someone deeply, we sometimes criticize them more. As the Hazaras say: “You complain more about the one you care about most.” So don’t expect people to always bring you flowers –

sometimes they’ll bring a thorn too. Just like life does. But you’ve learned to love even the thorns.

It reminds me of a friend of mine who once got badly wounded. His leg was injured, and he was in terrible pain. The last time I saw him, he had lifted his wounded leg toward the sun, frowning, and said, “This traitor hurts so much.”

I felt like he was talking to his wound as if it were a friend – complaining to it lovingly, as though saying, A friend shouldn’t hurt you this much.

And while listening to you, I felt the same tone in your words – as if you were saying to life, “Life, you shouldn’t hurt Fatema this much.”

And even when you speak with God, it’s as if you’re saying, “Dear God, no one should hurt Fatema this much. Fatema loves You so deeply – why, then, do You let her suffer so much?”

Fatema: Yes, Ustad, that’s exactly how it is. When I sit on my prayer mat – especially when I’m tired or feel hopeless – I say, “God, what wrong have I done? I’ve never hurt anyone. I don’t deserve this much pain.”

But my mother always tells me, “God gives the deepest pain to those He loves the most.” She once said to me, “Pain makes a person aware.” She tells me, “You are aware, and after all that you’ve been through,

you’ve become even more conscious.”

So now I also believe that pain awakens people. It makes them wiser, deeper, and more understanding of life.

Like in the book Man’s Search for Meaning, the writer was in a concentration camp – he suffered terribly, but through that suffering,

He found the meaning of life.

He said, “When a person knows their ‘why’ in life, they can bear almost any ‘how.’” And I think I’ve found my ‘why.’ Now I’m learning how to live with every ‘how.’

Royesh: The mystics say – quoting from a sacred saying attributed to God – that “whomever God loves most, He tests most.” Because when God inflicts pain on a servant, He longs to hear their voice – their cry, their whisper, their prayer – and through those cries, He feels that His servant has come closer to Him.

So tell me, Fatema – when you complain to God, when you argue with Him, when you wrestle with life itself, do you feel that this struggle brings you nearer to Him? Do you feel that, in some way, your sorrow has made you dearer, sweeter, and more intimate to God?

Fatema: Yes, Ustad. When a person confides in God, it gives a beautiful feeling – a kind of lightness inside.

It’s the sense that someone is always there, someone who understands you without words, who listens in silence. Even when He cannot be seen, He can always be felt. When I speak to God, it feels like there is someone who silently watches over me and understands me completely.

Royesh: If you were to title this story, what would you choose?

Fatima: I’m not sure, sir. You can decide. Choosing is hard.

Royesh: God keep you, Fatima. Be well. Love life-it is beautiful.

Fatima: Thank you, sir.

Comments (0)

Leave a Comment