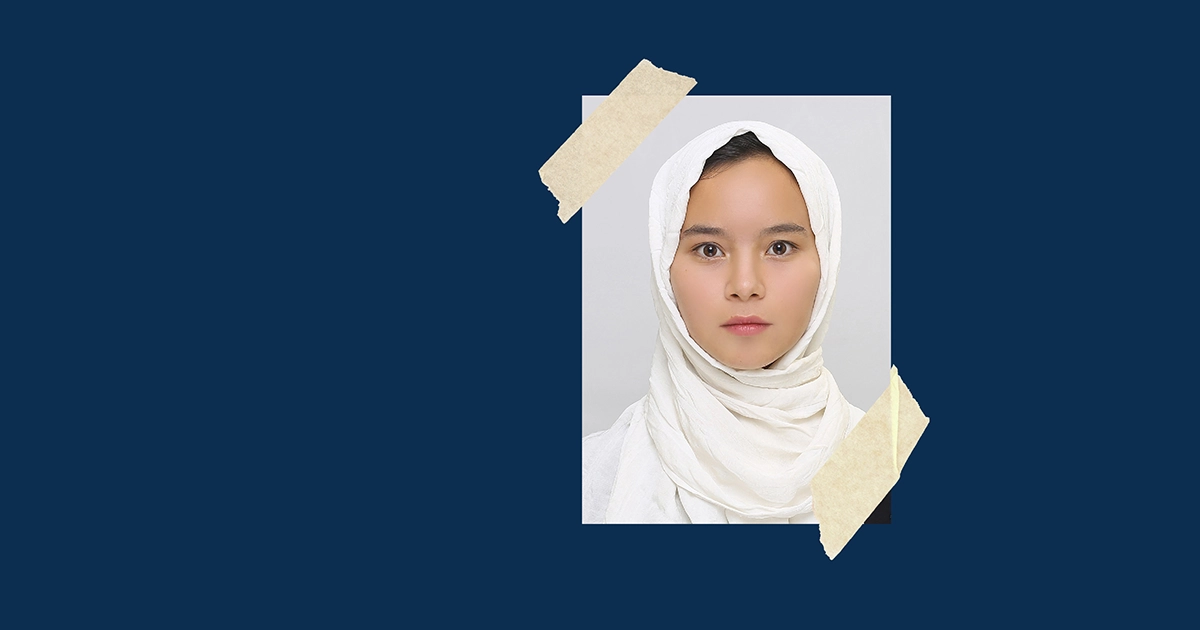

FutureSheLeaders (7)

Somaya Ahmadi, 17-year-old – Kabul, Afghanistan.

A testament of courage, growth, and unshakable dreams.

Born the seventh of eight children in a working-class family.

Grew up witnessing the quiet inequalities between girls and boys; but chose to rise, to learn, and to lead.

When the Taliban shut the doors of her school, she opened new ones through Cluster Education and Empowerment classes.

Her voice, questions, and leadership quickly stood out.

She built her own team, wrote passionately, led initiatives, and turned her anxieties into strength, her silence into speech.

Somaya’s dream is not only personal—it’s collective: a vision of a peaceful Afghanistan where dignity belongs to all, especially its women.

In today’s episode, we meet a girl who once walked in fear, but now walks with purpose—a FutureSheLeader shaping the path for others to follow.

Royesh: Somaya jan, hello! How are you?

Somaya: Hello, Ustad. Good day. Thank you—I’m doing well.

Royesh: So, how old are you now, Somaya? Tell me the truth.

Somaya: Ustad, you know you’re not supposed to ask a girl her age!

Royesh: Oh come on, you’re still a little one. No matter what you say, you’re not that grown-up yet to be worried about your age.

Somaya: I was born in 2008, and this month, I’ll be turning 17.

Royesh: Is that your real age—or the one written in your ID and passport?

Somaya: It’s the same—what’s written there is correct.

Royesh: And in your family, what number child are you?

Somaya: I’m the seventh child—three sisters and three brothers before me.

Royesh: So only Fatimah is younger than you? Or is there anyone else?

Somaya: Fatimah is the only one younger.

Royesh: That’s why you’re so close to her.

Somaya: Exactly. We’re very close now, though we weren’t that close back when we were in school. But after the regime change, when we both had more free time, we really became good friends.

Royesh: Somaya jan, tell me about your parents. Are they educated?

Somaya: My father can read and write, but my mother is illiterate. My father learned what he knows in the mosque.

Royesh: What did your father do to support the family—especially back when you were in school?

Somaya: In the beginning, he used to wash cars. But mostly, as far back as I remember, he was in Iran. Sometimes he came to Kabul. A few years ago, he had a small honeybee farm, but then a flood hit our area and washed the bees away. Now, he’s unemployed and stays at home.

Royesh: The house you were born in—was it your own, or were you renting or living in a borrowed space?

Somaya: When we first came to Kabul, we lived in Pul-e-Khoshk—that’s where I was born. Later, we lived in our own courtyard house in Kabul.

Royesh: Which school did you go to in Kabul?

Somaya: I started school at Homayoun Shaheed School. After completing Grade 6, I transferred to Zainab Kobra School.

Royesh: Did your older brothers and sisters also go to school?

Somaya: My two oldest sisters didn’t go to school. One of them studied up to Grade 4, but the other didn’t study at all. They’re both illiterate. As for my brothers—one graduated in journalism, another studied up to Grade 4 or 5 and then started working. The brother just older than me graduated from Grade 12.

Royesh: Among your siblings, who supported you in your education—and who didn’t really care?

Somaya: We were a big family, and most of the attention was given to the boys. For example, my older brother—the one just above me—was always the focus. They never told us not to study, but it was only after I proved myself that they started encouraging me. In Grade 6, I remember being constantly praised. My father would say, “Look at Somaya’s handwriting—you’re in Grade 12 and still can’t write like this!”

That upset my brother a lot. He used to say, “You have no right to compare me to a girl.”

So, I earned their encouragement by proving myself—by showing I was capable and deserved to continue my education.

Royesh: When did you first realize that being a girl in Afghanistan—in your society—comes with extra challenges?

Somaya: The family is like a small society. Honestly, I could see the differences right at home. I noticed how my brother had more opportunities than I did—whatever I had, he always had something better.

And that made me wonder: why was he considered superior to me? That’s when I began to realize that, in Afghan society, girls are often valued less than boys.

But over time, this difference started to fade in our family. They gradually realized that favoring one over the other wasn’t the answer. Even though I faced more challenges, I managed to prove myself—more than my brother.

Royesh: Was your family’s financial situation good enough to support both girls and boys to go to school without hardship?

Somaya: For my older sisters, it was harder—they couldn’t go to school and had to work at home. But fortunately, by the time I and my younger sister Fatimah were in school, things had improved a bit. My father was able to support us financially so we could attend school and even take extra courses.

Royesh: Did any of your brothers or sisters attend private schools?

Somaya: My brother did, but we went to public school.

Royesh: Which private school did your brother attend?

Somaya: He studied at Koshan School and graduated from there—finished Grade 12.

Royesh: When the Taliban returned, how old were you? And how did you first hear they were coming? What image did you have of them in your mind?

Somaya: That day, I was planning to go to my English course. On my way, I heard it had been shut down. I’m not sure if it was around 3 p.m. or a little later. So I turned back home.

That night, we were supposed to host some relatives. The guests were actually arriving at my uncle’s house next door, and that’s when I heard the news—“The Taliban are here.”

I got really scared. Even though there were lots of people around, they told me to go out and buy groceries. I said, “Why me? You always send the adults. Why now me?”

They said, “It’s okay. Just go.”

So I went. It was nearly evening—getting dark. I picked up what we needed—like dry bread and other things.

Even though I was wearing a long dress, I was still really scared. I didn’t take Fatimah with me because she walks slowly. I’m always quick—I even run sometimes.

People always tell me to slow down. But I’ve gotten used to it—I walk fast. Maybe that’s why they told me to go: “You’ll be back the fastest.”

So they put the responsibility on me.

Royesh: Do you mean the same day—August 15th—the day the Taliban entered Kabul, the day Ashraf Ghani fled?

Somaya: I think it was that day, but I can’t say for sure. I wasn’t really keeping track of dates back then. I just remember it was a Sunday or Monday. The next day, we didn’t go to school.

That afternoon, people were already saying, “The Taliban have arrived.”

Royesh: Had you heard anything about the Taliban before that? As a girl, did you know what it meant when people said the Taliban were coming? What would happen if they took over?

Somaya: I hadn’t heard much. I just knew that if the Taliban came, my mother’s chadari—the one she kept folded inside her chest—would come out.

She never took it out. Sometimes, during housecleaning or on a special occasion, I’d try it on. And my mother would say, “God forbid the day ever comes when you or I will have to wear this.”

So when the Taliban arrived, that chadari was the first thing I thought of—I put it on. It felt awful. That moment, I thought, maybe we won’t be allowed outside anymore.

My mother told us, “There’s no more school now.”

And from the very next day, I didn’t go to school again.

Royesh: When we started the Cluster Education program, you were among the very first students who joined. How did you hear about Cluster Education or the Empowerment classes?

Somaya: I heard about it from a friend. It was the beginning of the new year—probably 1401, though I’m not exactly sure.

I asked my friend, Malika Hosseini, what she was doing these days. She told me she was part of Cluster Education and mentioned its programs. I asked her where it was. On the fourth day of the new year, I went to the school and enrolled in Cluster Education.

It turned out to be a really interesting experience.

For the first two weeks, I didn’t even know about the Empowerment class. But the chemistry teacher would tell students who gave strong answers, “You’re capable—you should join Empowerment.”

I didn’t know what Empowerment was, so I asked her. She explained it was a class held on Saturdays and Wednesdays. I got curious and joined.

Royesh: Did Fatimah come with you to Cluster Education, or did she join later?

Somaya: Fatimah and I joined together. We started at the same time.

Royesh: On your first day in the Empowerment class, what kind of feeling did it spark in you? Did you sense that it would open up a new world or new ideas?

Somaya: At that time, I didn’t really know what to expect. I was mostly focused on English and wanted to begin with the Cluster Education classes.

That day, I think you were talking about “problems”—discussing as the main topic in the class.

A question popped into my head: Which is more important—the problem itself or finding the right solution to it?

I remember asking you that question—it was my first day in the Empowerment class. The whole environment felt new to me.

In the mornings, when I’d get up, I would usually force Fatimah to come with me—she’d complain that it was too early and no one else leaves the house at that time.

Our home was far from the school, and I didn’t want to go alone. I’d say, “Come on, Fatimah—let’s go together. We’ll practice English, learn something new.”

At first, I had to push her to come, but after two weeks, she became even more excited about the program than I was. We started attending regularly.

Royesh: In the Empowerment classes, we encouraged you to work in groups. The goal was for you to discover your strength within a collective—so that you wouldn’t feel isolated or overwhelmed by the pressure that loneliness can create for girls in difficult conditions like Afghanistan.

Who were your first friends in the program? The ones you worked with in your first group—who were they, and what kinds of things did you do together?

Somaya: In the beginning, we didn’t have a team right away, but I started getting to know other girls.

Later, I formed my own group—we called it the Tabassum team. On the first day, I connected with Parwin, Zainab, Tamanna, and Shukria. We built our team together, and it was a really interesting experience.

We used to gather not just for Empowerment activities, but also to support each other.

We tried to stay careful—not to get into trouble while filming in public. We didn’t want people to question us like, “Why are you recording videos?” or for the Taliban to stop us and ask what we were doing.

In the beginning, I was very afraid of the Taliban. I always wore long clothes and made sure I followed all the safety precautions—just to avoid any trouble.

But working with the girls was a wonderful experience. It was the first time I really experienced teamwork. Before that, we sometimes worked together at school, but it was never that intentional or organized.

Royesh: You were one of the students who wrote a lot—you sent many messages, shared your thoughts and reflections through writing. What kind of feeling did writing give you? What did you learn from it as a new experience?

Somaya: Writing helped me a lot—in every way. In my personal life—I’m not sure why—but I was often very stressed. My mind was constantly busy, and writing helped me manage that.

Sometimes I would write about things I experienced. Sometimes I would take something that happened and relate it to a scientific concept or something similar.

Now, I’ve become more intentional about my writing. I’ve collected 20 pieces, and I plan to publish them soon as a small book.

Royesh: You were also one of the students who messaged me the most. Among all the girls in Cluster Education, I think you’re the one I’ve corresponded with the most—responding to your many thoughtful messages. What made you write and message so frequently?

Somaya: First, I was very curious. And once I joined the Cluster Education environment, I felt like I could do a lot. Every time I had a new idea—whether it was a written piece or a group activity—I would send it to you.

I think I sent you at least two messages or videos every week. That became a meaningful experience for me. It kept me engaged with my lessons and programs, and it pushed me to keep creating something new.

It also helped clear my mind—and it gave me a really good feeling.

Royesh: In one of the early Empowerment sessions, there was a guest speaker who said, “I wish I could be an Afghan girl.”

You responded, “Being an Afghan girl is not easy.”

You said one can only truly understand what it means to be an Afghan girl if she is a girl, an Afghan, living inside Afghanistan, under Taliban rule.

What did you want to express with that message? What exactly were you feeling at the time—three years ago, as an Afghan girl under Taliban control—that you wanted the foreign audience to understand?

Somaya: That guest’s comment really stayed with me. I remember I was wearing a long dress that day—but I still felt very uncomfortable. I don’t even know exactly why; I just remember feeling bad.

And when she said that, I thought—Yes, maybe from the outside, being an Afghan girl looks brave, even inspiring.

But in reality, it’s incredibly challenging. It’s not just about wearing hijab or modest clothes. It’s about being afraid—even though you’ve done nothing wrong.

You can’t walk freely in the street, you constantly feel fear, and you face so many restrictions.

So, to wish you were an Afghan girl is completely different from actually being one—living in Afghanistan and experiencing those hardships firsthand.

What I wanted to say was: This isn’t something anyone can simply choose or imagine. It’s not easy at all. And it’s not just about courage—it’s about surviving constant fear, limitations, and injustice.

Royesh: You seem like such a calm girl now. But back then, you were often very anxious, emotional—even to the point of tears when speaking. What kind of pressure were you under during that time?

Somaya: It was a really hard period. It took me a long time to find even a bit of peace with myself. There were family problems, and sometimes… like when the Taliban were rounding up girls, I felt so much fear.

All of it made me constantly ask myself: Why do I have to go through this?

We weren’t going to school or university. We didn’t go to parks, we didn’t go out, we didn’t go to the gym—basically, we were just at home. And even when we did go out, we were treated harshly.

I was really afraid—and that fear made me extremely anxious. Even now, when I watch videos from that time, I can see how distressed I was. I had so much stress that my hair started to turn white. I was very thin, and I couldn’t focus properly.

During the time I was attending Cluster Education, I was barely eating.

At one point, I had stomach problems. When I saw the doctor, they said, “You’re under too much stress—you need to reduce it.” But I didn’t even fully understand why I was so anxious. There were exams too—we had monthly exams at Cluster, and I felt pressure from that as well. I used to take the smallest things so seriously.

Now, I try to focus more on my goals—and not let everything else affect me so much.

Royesh: I’d like to revisit some of the challenges I faced with you—as your teacher and mentor—because I’m curious how you, Somaya, moved through those moments.

You were often a very critical and skeptical girl. You carried a lot of bitterness—especially toward men, toward patriarchy, and the male-dominated culture around you.

Sometimes the words and expressions you used about men were extremely sharp. What were you going through at that time? Where did that anger and distrust come from? Was it the Taliban who made you feel that way? Was it your family? Your society? History? What was the root of that bitterness?

Somaya: I was very sensitive back then. I still am—but now I try to manage my anxiety better. What made me feel so bitter was this: I hadn’t done anything wrong.

And yet, every time I went outside or was in public, I’d hear things—like how everything happening to girls in Afghanistan, like being forced to wear hijab or being banned from education, was somehow justified.

When I heard people say that, it really got under my skin. I would think, What did women ever do to deserve this?

They’d say things like, “It’s because of improper hijab,” or “At least now things are calm—this is better.”

Most of the men seemed satisfied with the situation, and that deeply upset me.

When I watched the news, I’d see poverty wasn’t being addressed. In Kabul, we had real problems—like electricity shortages. And I’d think, They’re not fixing any of that. They’re just obsessing over what women wear.

If they put the same energy into solving real issues instead of controlling women, the world would be a much better place.

I was hypersensitive—any comment would affect me deeply. And if I hadn’t taken things so personally, maybe I could have moved past that stage more easily. But because I did, it made me grow more resentful—especially toward men.

Royesh: I could see that bitterness in your eyes, in your behavior. But I also witnessed something else—your resilience, as the English word goes.

You didn’t give up. You kept pushing forward, step by step.

What helped you stay strong against that bitterness? What gave you the strength to hold on to hope and move forward—to become the calmer, more grounded Somaya you are today?

Somaya: I started working more on myself. I learned not to let every word or opinion get to me. When you have a dream—when it becomes your goal—you need to focus all your energy on that.

I also realized that if I hold on to hate, I’m only hurting myself. Bitterness is like garbage—if you carry it around, it’s like turning yourself into a trash bin.

It doesn’t benefit you at all.

So, I began focusing on personal growth. I improved my English, worked on new skills, and stayed engaged with my Tabassum team in the Peace on Earth Game.

That teamwork helped me a lot. It changed the way I saw men, too. I stopped being hostile toward them.

I began telling myself: Not all men are like those who oppress women. Maybe there are better men—I just haven’t met them yet. And I believed that if we kept learning, kept teaching, kept showing up—we could help change this society.

I’ve always been a dreamer. And I still believe things can change. Nothing has to stay the way it is.

Royesh: Sometimes in life, a small spark—a book, a sentence, a realization—can become a turning point. Have you ever had such a moment in your Empowerment journey? A moment that helped you move closer to love, compassion, and forgiveness—and further away from anger, revenge, or harshness?

Somaya: Yes, I have. One of those moments came through a video project I worked on about the refraction of light. I imagined myself as a beam of light.

When light enters glass, it bends—it breaks. For me, that glass was like a challenge or hardship. I saw it as life breaking me—forcing me off my original path. But then I realized: when light exits the glass, it returns to its original direction.

So even if I’m bent or broken for a while, I can find my way back. That became a powerful metaphor for me. I had compared that to my own life.

Sometimes, I felt like light passing through glass—bent, even shattered—pushed off my original path. But I saw myself as someone determined to keep going.

Just like the light that bends when it enters the glass but regains its path when it comes out—I believed I could return to my direction, no matter how difficult the passage.

That was one of the most meaningful lessons I experienced.

In Cluster Education, I also want to thank my chemistry teacher, Ms. Kimia. She explained things so clearly—and chemistry became one of my favorite subjects.

One lesson that stayed with me was about how sodium reacts with chlorine. Chlorine, on its own, is poisonous—green, and deadly. But when it reacts with sodium, it turns into table salt—something we use every day, something essential.

That reaction really moved me. It made me think: every person we meet can change us—just like chemical elements interact and transform. And how beautiful it is when we connect with truly good people—people whose true religion is humanity, who leave behind values that make the world better for others.

Human beings can come together, speak, listen, work together, and through those connections, transform. They can let go of their harmful traits and become something essential—like a substance the world needs every day.

Royesh: Are there any stories or lessons from Empowerment sessions that helped you understand your chemistry or physics classes better?

Somaya: Yes, I think the topic of communication really stood out. A human being is someone who both receives and gives power.

And in this exchange, it’s so important to know how to connect with the right person—to express what you want and to enter a mutual interaction.

It’s like in chemistry—there has to be balance. You and the other person need to be on the same level, like a balanced equation, where the numbers match on both sides. What you bring into that interaction has to align with what the equation requires.

Sometimes I thought about these things a lot—even though I never made a video about it.

I did write something on it once. This way of thinking really helped me grow—to become a better person and to walk the path that brought me to where I am today.

Royesh: Which concepts from Empowerment helped you become more aware of your school lessons and life experiences—helped you frame them, even formulate them more clearly?

Were there any terms or ideas from Empowerment that made it easier for you to turn insights into action?

Somaya: Empowerment taught me to dream big. But it also taught me not to stop there—to turn the dream into a goal. That means it had to be time-bound and, as they say in English, SMART—specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound.

The Empowerment exercises helped me define goals that were realistic and reachable for me—without denying the reality around me. I learned to accept the reality, but still work toward my ideal. That helped me grow even within my own family—by accepting what exists, and then trying to improve it.

It gave me the courage to take the Duolingo exam. That felt really good—and later, I got into the American University of Afghanistan. I studied there for five or six months. But then, because of the Trump-era policy changes, the program got canceled.

I felt really discouraged. I thought, I worked hard for eight months—and now it’s all gone. I had to start over again—from zero—to apply to a university and try to get admitted.

Eventually, I accepted what happened. I moved to Quetta and started Grade 12 again. Now, I’m working toward my dream again.

And all of that is because Empowerment had a practical role in my life.

I even brought my Empowerment notebook with me. It has all my notes—every lesson written down, with dates. When we had guest speakers and I learned something new, I wrote that down too.

Sometimes when I flip through it, I realize I’ve forgotten some of the lessons—but I’m living them in my life.

For me, it’s the practical side of Empowerment that matters the most.

Royesh: One of the most important concepts in Empowerment was learning to identify limiting beliefs and transform them into supporting beliefs. We live in a society that constantly imposes barriers and challenges, so it’s natural to feel doubtful or discouraged about our dreams.

What were some of your biggest limiting beliefs—as a girl, as a student in Afghanistan—that you managed to overcome?

Somaya: One of the biggest limiting beliefs I had was this: Schools were officially shut down. No girls were going to school anymore.

So I asked myself, Why should I continue studying? If there’s no outcome, why should I keep trying?

But I managed to overcome that belief.

Another challenge was the resistance I faced from my own family. Convincing them that my education mattered—even without a formal degree—was hard. I had to help them believe that my time and energy were not being wasted.

Then, when I set the goal of continuing my education outside Afghanistan, another limiting belief came up: Would my family even allow it?

Even if I improved my English and did everything I needed to, what if they said no?

And on top of that—I didn’t even have a passport. All of this made my goal feel out of reach. No matter how hard I worked, it all seemed impossible.

But slowly, I kept pushing forward. I got my passport. I moved away from home. And now I live on my own.

It all started with small changes I made within my family—until they began to support me too.

Looking back, it’s kind of surreal. If someone had told me four years ago that I would go to Pakistan, I would’ve said, No way!

As a girl, it felt completely out of reach. But I kept trying.

Now I know: even if your dream seems impossible, just ask yourself—What is the next small step I can take right now? And the next one after that?

Those small steps—taken consistently—are what lead you toward the dream.

Royesh: As a 17-year-old girl today, how do you understand some of the basic concepts we explore in Empowerment classes? For example—what does freedom mean to you? What feeling does it give you? And what about dreams—what does it mean to have a dream?

Somaya: If you had asked me in the past what freedom means, I would’ve said: It’s being able to do what you want—within the law. Like having freedom of speech, freedom of dress, freedom of choice.

But over time, I’ve realized that putting freedom into words is difficult. It’s something that comes more from within than from outside.

Things can happen around me, but freedom is something rooted inside me. I can’t really say if I’m free in every sense, or that I’ll always get everything I want in time.

But for me now, freedom feels more like something internal—something no one can take from you, because it lives inside you.

And about dreams—a dream is like a driving force for me. It’s something beautiful. When I wake up in the morning and remember it, it completely recharges me. Without a dream, even the simplest daily tasks would feel boring and hard. Life itself would start to feel empty.

But right now, because I have a dream that’s truly beautiful, I feel like everything in the universe is aligning to help me reach it. I have no doubt—because I believe. And when you believe, everything starts falling into place.

Royesh: One of the core concepts in Empowerment is the idea of the Self. Many of our exercises begin with the word Self. What does Self mean to you?

Somaya: Self means inner power—the central force inside us. I think of it like the nucleus of an atom, with all other powers—like electrons—spinning around it. They all draw their energy from that center.

Royesh: If you had to define the Self, how would you describe it?

Somaya: Self can’t really be defined. If I had to give it a sign, I’d say Me. It’s Somaya.

Royesh: And who is Somaya?

Somaya: Somaya is me. And me—that’s Somaya.

Royesh: How do you see your relationship with things that are often connected to the self? For example—your body? Is it the same as you, or something separate? What about your name—does your name belong to you, or define you?

Somaya: A name is just a label—something placed on top of the self. It points to me, but it’s not the whole of me. “Somaya” is just a sign for the person I am.

Royesh: Now, what about other concepts we attach to the self—like losing yourself, selfishness, or forgetting the self? How do you define something like losing your self?

Somaya: Like I said—Self is the inner core. It’s the nucleus, and everything else—money, knowledge, power—spins around it. When someone loses themselves, it means they’ve become disconnected from that center. They let something—wealth, power, even knowledge—overwhelm them. That’s when we say someone has lost themselves. For example, when someone gains too much money and completely changes—they’ve lost their self. They’re no longer who they truly are.

Royesh: You carry within you a mix—between your real self and your ideal self. How much have you nurtured that self? Would you say that Somaya today is a balanced person? How well do you understand your reality? And how much are you moving toward your ideal?

Somaya: If you try to pursue your ideal without accepting your reality, you’ll face a lot of challenges.

In my view, you have to acknowledge reality—whether it’s your family, your society, or even something inside yourself that gets revealed.

Yes, I have a dream. But I can’t ignore the fact that I live in a traditional society, or that I’m from Afghanistan. These are real things—and I have to face them.

Still, I dream big. I want to complete my education, serve my community, and help bring peace to Afghanistan. That dream may seem out of reach at first—almost impossible. Especially when you look at the reality on the ground: There’s no peace.

There are so many challenges. And if we take Afghanistan as an example, it’s at least a half-century—or even a century—behind more developed nations.

Achieving peace and progress feels overwhelming. But if we start by accepting that reality—and still work toward our dream—if we turn that dream into a goal and take steps toward it, then everything becomes possible.

Royesh: In your view, where does a person’s strength lie—in their reality or in their ideal? Where does their weakness lie?

Somaya: I believe our strength lies in our ideal, and our weakness in our reality. Because reality can be very harsh—sometimes even crushing. There are moments when your reality tells you, You can’t do this. But we shouldn’t ignore it.

Reality could be the traditions of your country, or the culture you’re living in.

You have to accept that. But your ideal—your dream—that’s where your energy comes from.

Yes, the reality may be bitter. But your dream—that sweet vision in your mind—gives you the power to move forward, even with your reality in view.

Royesh: If we compare Somaya to an eagle—would you say your strength and weakness differ from the eagle’s in terms of reality and ideal?

Somaya: In reality, the eagle is powerful. It flies, it’s a strong creature. But its dream—its ideal—might be limited compared to mine.

In reality, I may be weak—especially when compared to an eagle. But in terms of ideals, of vision, I am far more powerful.

Royesh: What power does an ideal give you—as a human—that allows you to rise above even the strongest creatures like elephants or eagles?

Somaya: The power of an ideal is immense. It gives us the ability to dream big—then break that dream into goals, make a plan, and take action. For example: Where do I want to be in five years? What will I do? How much money will I earn?

That kind of thinking—strategic and forward-looking—is what sets human beings apart from other creatures.

Royesh: Right now, you’re living in difficult conditions—as a girl, as a refugee. Women in Afghanistan are facing enormous restrictions. And yet, you dream of leading a peaceful, better world in twenty or thirty years. Where does that belief come from? How do you truly believe in your dream—not as fantasy, but as something real and possible?

Somaya: We are a generation with a big dream—a dream of building a human society where everyone’s rights are protected, where no one is denied their dignity.

And where does that dream begin? It begins in the pain. In the injustice we experience. That’s what makes every lesson I study, every subject I choose, deeply meaningful.

My dream is to return to Afghanistan and be part of creating real, positive change in my society.

Royesh: The Taliban took over Afghanistan by building a strong group. If you want to reclaim Afghanistan from forces that bring darkness—like the Taliban or anyone else—you’ll also need to build a strong group.

How much do you believe in group work? How much of a team-builder are you? Or do you tend to work alone?

Somaya: Group work is incredibly valuable. When you work with four or five people, that means five different minds are working on one goal—and each person takes responsibility based on their strengths.

That’s what makes the outcome better. When teamwork is purposeful, like what I experienced in the Peace on Earth Game, its impact is beautiful.

Yes, working alone can be effective—and even fast. But it also gets exhausting. When you work alone, the pace can be fast—you can move forward quickly. But at some point, it becomes exhausting. You get tired, even disheartened. But when you’re working with five others—as a team—your shared goal becomes much more achievable, even beautifully executed.

In my view, true strength is in the collective.

Royesh: There’s a difference between ambition and vision. Ambition reflects your personal dreams and strengths—it’s focused on the individual.

Vision, on the other hand, connects you to a group—a larger cause. How much of Somaya is driven by personal ambition? And how much do you operate with vision—feeling connected to others and a shared mission?

Somaya: At first, I was mostly an ambitious person. I had very personal dreams—things that were only about me. They didn’t really involve anyone else.

But once we formed our group—and we’re still connected today—it helped me realize the importance of vision.

Now, we share a collective purpose as a team.

So today, I see myself as someone who has found a balance between the two. I still work toward my personal goals—but I’m also committed to group work, to shared goals, and meaningful collaboration with others.

Royesh: Let’s imagine five or ten years from now, we find Somaya at a university, a research center, or in a position of leadership. If someone asks you then, “Somaya, how faithful have you remained to the words you’re saying today?”—what would your answer be? Would you say, “Those were just beautiful memories of my past, and I’m grateful for them”? Or would you say, “Those words shaped who I became—I built teams, empowered people, and created real change”?

Somaya: Based on what I’ve already experienced—if I look back five years, I never imagined I’d be where I am today. Now I see myself as someone ambitious, with real inner power. And I believe, if I keep working, my future might turn out even better than what I imagine. I’ve lived that truth before.

Royesh: Many people your age had beautiful dreams too. They once said, We’ll rebuild the world. We’ll serve our country. But when they turned 30 or 40—after university, after becoming doctors, engineers, people of power and privilege—they slowly became more individualistic.

They focused on their careers, their families, their comfort. Why do you think your story will be different? What makes you believe Somaya at 30 or 40 won’t become just another version of that?

Somaya: Being ambitious, having personal dreams—that’s not harmful. But I believe the real strength comes when we move forward with others—when we have a shared vision.

That’s what gives power to a cause. And I believe I will stay committed to that path.

Royesh: So you think that if you stay true to your ambition, but also act with vision and as part of a team, you’ll grow stronger—not weaker?

Somaya: Yes—I’ll become stronger. I do have personal dreams, but I also want to be part of a collective that is powerful. And I want to align myself with that collective—because that’s where real strength comes from.

Royesh: What’s your takeaway from observing others—people who chose to act individually and reached personal success? Do you think they are truly powerful now, or do you see them as lacking something?

Somaya: I think those who have ambition and work hard to achieve it—they don’t harm anyone. But they miss out on the strength that comes from being part of a group.

Every human being, at some point, will need that collective strength. We all eventually turn back to it.

Royesh: In group work, we learn to give what we have—to offer our knowledge, our skills, our resources to others. How generous are you in that sense? How much of your knowledge and awareness have you shared with your group? How many people have you helped learn, empowered, or encouraged to start their own groups?

Somaya: One thing I’ve always tried to do is share whatever I had access to. Since I was one of the top students in the Cluster program, I made it a point to help others. If students had questions, I’d answer them—or we’d work together as a team. Especially in subjects like math and physics, where I was strong, I made sure to help my classmates and share what I knew.

Royesh: If you compare the 17-year-old Somaya of today to the 14-year-old Somaya from three years ago—how much more hopeful, kind-hearted, or optimistic are you now?

Somaya: That’s a really good question. Today, I feel like I’ve reached a deeper sense of peace. Three years ago, I was very anxious and stressed.

Back then, I used to feel jealous when others achieved something.

Now, I believe that everyone gets what they earn—according to their own effort and ability. Nothing is ever truly wasted. If someone succeeds, I say congratulations. Because if I feel jealous, I should remind myself: I need to work harder.

If I feel bitter or refuse to celebrate someone else’s success, it doesn’t affect them. They don’t need anything from me.

So now, I try to be honest with myself—more optimistic, more sincere toward others. If I see something good, I say it. And I try to let go of jealousy.

Royesh: In Empowerment, one of the key things we learn is gratitude—

to appreciate even the smallest kindness someone offers in difficult times.

Because no one owes us anything. No one is our servant. No one has to do anything for us. We are each responsible for our own lives.

Somaya, as a 17-year-old girl today—how much have you learned to be grateful? To your parents, your teachers, your classmates— do you feel that this sense of gratitude has made you a better person than you were three years ago?

Can you now naturally talk to your parents and say, Father, Mother—I appreciate what you’ve done for me. I know how much you’ve given.

Can you tell your teachers, You were there for us in difficult times. You gave us knowledge, and I’m thankful?

Somaya: I believe gratitude is one of the best qualities a person can have.

Personally, I feel truly grateful. Even for the oxygen I breathe. For the opportunities I’ve been given. There’s a saying: “Gratitude brings more blessings; denial takes them away.”

Be thankful for everything you have. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have a vision, or an ideal, or dreams—you should have those too. But also enjoy what’s already in your hands.

For example, if your family supports you, if they take interest in what you’re doing—that’s a blessing. If your father or mother smiles at you when they see you—that alone is something to be grateful for.

Lately, my father and I have grown really close. We’ve built a strong bond—and I’m truly thankful for that. I’m really grateful that I have a father with whom I share such a strong connection—despite the large age gap between us. I appreciate that he understands me. Even though he’s not a girl, and he’s much older than me, he still gets what I’m trying to say.

We have a bond, and I’m truly thankful for that. When I do something—take an action—he knows what Somaya means.

Royesh: In Empowerment, we talked about the three levels of gratitude: The first is expressing thanks with words—when someone gives you a gift or a blessing, you say, “Thank you.” The second level is using that blessing wisely—making good use of what you’ve been given. And the third level is to increase the blessing—not just use it well, but multiply it.

Somaya, when it comes to the blessings you’ve received—whether from God, your parents, your teachers, or your classmates— which level of gratitude do you think you’re practicing?

Somaya: If I reflect on myself and my sense of gratitude, I believe I’m at the level where I try to increase the blessings.

For example, the respect I showed to my parents— whatever blessings they gave me, I used them wisely. And that helped raise the value and dignity of girls in our family.

Fatimah, too, became part of that journey. The blessings in our family grew. I don’t think I’ve ever been ungrateful for the gifts God has given me, or for what my family has offered. And because of that, I feel like I’ve been able to attract even more blessings into my life.

Royesh: Of the three levels of gratitude we talked about in Empowerment—which one do you find the easiest? Is it really easy for you to just open your mouth and say thank you?

Somaya: I think speaking is the easiest. If someone helps me—even in a small way—I usually say thank you or bless you. But I believe actions matter more than words.

Royesh: But truly—do you find it easy to say it out loud? Do you see people around you actually expressing thanks with their words? Or do many people find that hard? And for you—do you find it natural to thank a teacher or a classmate? Or do you sometimes think, Why say it? They already know?

Somaya: No, I do think verbal gratitude is simple—and I say it often. If someone does something kind, I’ll thank them. But for me, it’s especially important that words and actions match. If someone gives you a notebook, for example— you can say thank you, but if you tear it up or waste it,

then your actions say something very different.

That’s ingratitude. And in my view, it’s not enough to express thanks with words— you need to honor the blessing through how you use it. Even if the blessing doesn’t grow—at least don’t destroy it.

Royesh: Yes—and it’s important to remember that all three levels of gratitude matter. Words matter—language is one of the most beautiful tools we have to express what we feel inside. Using a gift wisely shows we understand its value. And growing the gift—adding to it—shows our creativity.

Let me ask you maybe the last question: How much do you believe in female leadership—as a distinct and different kind of leadership?

Do you believe the kind of leadership you and your peers are practicing can actually solve deeper problems in society—like violence, hatred, and revenge?

Somaya: I truly believe that if women lead a society, many problems can be solved. In male-dominated societies, things tend to become harsher—even if there is progress in other areas. But you still feel the absence of women.

Female leadership brings more peacefulness. And our society, the way I see it now, urgently needs female leadership. We lack women in decision-making—in ministries, in the cabinet. And every decision ends up being made by men.

At first, people might say, “It’s okay—men make logical, less emotional decisions.” But over time, the absence of women—their silence, their lack of power— causes the society to move backward.

In my view, a society without women—without their voices, leadership, and presence— cannot grow. It cannot thrive.

Royesh: So when you say female leadership, do you mean we should temporarily dismiss the men, send them home for a while, and let women take over their seats—governors, ministers, presidents? Is that what you’re imagining?

Somaya: Not at all. I don’t believe we need to replace men or cancel their presence in society. What I believe in is balance. If we have four capable women leading an institution, it’s okay to have two capable men alongside them.

What matters is how they lead—whether they manage society with wisdom and fairness. And I truly believe that where women lead, society becomes more humane. If you look at families, for instance— in households where mothers are respected and lead the family, there’s a kind of harmony and order. That order at home is a small example of what female leadership can bring to society at large.

Royesh: Here’s a slightly more controversial question: Some say that among the Hazara people, as girls began to participate more and take on more leadership, the overall tendency toward violence has decreased. Even Hazara men seem less drawn to war and aggression. Do you believe that?

Somaya: Yes—I believe that’s true. And it’s not just among Hazaras. In other societies too—take Japan, for example. I once read that Japanese men tend to speak and act with a kind of gentleness— almost like a feminine touch in how they relate to others.

Men, by nature, may carry more intense energy, more aggression— but if that energy is guided—if it’s shaped— women can help lead both society and men toward peace and emotional balance. With women in leadership,

societies can become less violent and more compassionate.

Royesh: Two of our earlier guests in FutureSheLeaders said that during the Hazara Culture Day celebrations, Hazara people released their energy through joy—through dance, singing, and celebration.

They saw this as a sign of women’s growing role. Do you also believe that Hazara Culture Day reflects more of a feminine cultural identity?

Somaya: Absolutely. The Hazara Culture Day was beautiful. There was music, dancing, singing— and all of it carried a peaceful and joyful spirit. Women and girls participated with confidence—dancing, singing, celebrating. Or even those who celebrated Mother’s Day yesterday…

Royesh: So you would say it had a clearly feminine tone?

Somaya: Yes, exactly. The whole atmosphere was full of color and grace— especially with how women were dressed and how they carried the joy of the celebration. It truly felt like a feminine celebration of identity.

Royesh: If next year you were to lead the Hazara Culture Day yourself, what new symbol or element would you add to the event as part of female leadership?

Somaya: As a leader, I would try to emphasize even more respect for women. There’s a quote I once read—unfortunately, I forget who said it—

but it goes something like: “If you want to understand the condition of a society, look at how its women live.”

That has stayed with me. My hope is that by the next Hazara Culture Day, our society will be more humane, and that the situation for women in Afghanistan will have improved.

Royesh: Somaya, you’re 17 now. What’s your message to the women and girls of Afghanistan—those older than you and those younger?

Somaya: My message is: Never be ashamed of being born a girl in Afghanistan. Never let fear define you. You are valuable, you are beautiful, and your presence is part of what makes this world whole.

Royesh: What would you like to say to your parents?

Somaya: From afar, I kiss the hands of my parents. I’m deeply grateful for all they’ve done— for creating space for me, for standing by me. And I pray they live long, happy lives.

Royesh: What’s your message to the Taliban?

Somaya: Nothing harsh— just that I hope they choose to be human. I hope they accept the existence and worth of women, so that we can live in a truly human society.

Royesh: Thank you, Somaya. I hope next year we see you even happier, stronger, and more Somaya than ever.

Somaya: Thank you, Ustad.

Comments (0)

Leave a Comment