FutureSheLeaders (2)

Royesh: Hi Suraya Jan!

It’s a real pleasure to have you in this special edition of FutureSheLeaders. Today, we want to reflect on your journey—your experiences with learning, education, peace-building, and even the challenges of migration. My hope is that this conversation not only gives you a moment to share your story, but also inspires your peers. What matters most is uncovering those parts of your life that show how you’ve grown, the transformative spirit you carry, and how others can relate to your path.

Let’s begin with you. Tell us a little about yourself—where were you born, what was your early life like? How old are you now? Could you also share a bit about your family background—your parents’ education, your brothers and sisters, and what your living situation is like today?

Suraya: Hello, Ustad! I hope you’re doing well. I’m really happy to be here in this program and to have the opportunity to share my story and some of my experiences.

My name is Suraya Mohammadi. I was born in Malistan district of Ghazni province, and I’m 17 years old. Unfortunately, both my father and mother are illiterate. But my brothers and sisters managed to continue their education and even pursue higher studies at the university level.

Royesh: How many of your brothers and sisters are older than you, and how many are younger?

Suraya: I have one younger brother, and among my sisters, I’m the youngest.

Royesh: So, you’re almost the last in the family!

Suraya: Yes, you could say that.

Royesh: When did you move from Malistan to Kabul?

Suraya: I actually started school in Kabul. We moved in the year 1393 (2014), and that’s when I began first grade at Sayed al-Shuhada School. As soon as we arrived in Kabul, we decided to enroll in school.

Royesh: Was the house in Kabul your own, or were you living in a rental?

Suraya: It was a rental house.

Royesh: During your time at Sayed al-Shuhada School, one of the most tragic events in recent memory took place—the attack on your school. Do you remember how that incident happened? What grade were you in at the time? Where were you when it occurred?

Suraya: The attack on Sayed al-Shuhada was, without doubt, one of the most painful experiences of my life. I had been studying at that school since first grade. We enrolled in 1393 (2014), and I continued there until eighth grade, right up to the fall of the government.

Studying at Sayed al-Shuhada was never easy. It was a public school located in one of the most deprived areas of Kabul. Conditions were harsh, but our determination was strong. I remember that many times, we didn’t have proper classrooms. We studied under tents, under the scorching sun, and even under staircases, taking turns with other classes. Each class would spend one week inside the classroom, then rotate outside—sometimes under a tent, sometimes directly under the sun, sometimes squeezed into a corner beneath the stairs.

I vividly recall when we were in sixth grade—the heat was unbearable. To cope, we would bring large plastic bags from home to create makeshift shelters for ourselves, just to block the sun. Despite these conditions, the girls came every day full of enthusiasm, excited to learn. That spirit kept us going.

Many of my classmates faced extreme hardship. Some of them would weave carpets at night and come to school during the day, just so they could afford basic school supplies—things like notebooks, pens, and even shoes. Families in that area struggled every single day to meet their most basic needs.

It was during eighth grade, on the 18th of Sawr, 1400 (May 8, 2021), when that tragic incident happened.

Royesh: Sorry to interrupt, Suraya—but before we talk about the incident itself, I remember that there was a time when students at Sayed al-Shuhada organized protests. You protested for teachers, classrooms, and books. Were you part of that movement? What were you demanding?

Suraya: Yes, I was part of it. At that time, we had a severe shortage of teachers. On days when we had four or five classes scheduled, we were lucky to have teachers for even two or three of them. The rest of the time, the classes were empty.

Since I was a class representative, I used to prepare lessons at home and then teach my classmates myself. Many of us did that. But the need for proper teachers was urgent, so we all decided to speak up.

The distance from my home to school was almost an hour on foot, and many other students had the same challenge. We felt it was unfair to walk that far only to sit in empty classrooms. So, when we raised this issue with the school administration and the head of the teachers’ department, they told us that if we wanted the problem solved, we should take it to the government through a protest.

I remember that a representative was selected from each grade block to attend meetings and plan the protest. I was chosen as one of the representatives for the eighth-grade block. In those meetings, we discussed our approach and strategy. Our demand was simple: we wanted teachers so we could continue our education. That was all we were asking for—a fair chance to learn.

Royesh: At that time, on average, how many students were there in each class?

Suraya: Each class had around 40 to 50 students.

Royesh: That many in just one class?

Suraya: Yes, in one class.

Royesh: When you think about the shortage of teachers, was that just for one year, or had this been a problem in previous years too?

Suraya: Up to sixth grade, we didn’t feel the shortage too much because the subjects were fewer, and we managed to continue our lessons. We had teachers then.

But after sixth grade, the number of subjects increased, and so did the need for teachers. By the time I reached eighth grade, the shortage was critical—across all grades. Even the twelfth-grade students, who were preparing for the university entrance exam, were deeply worried. They kept saying, “If we continue without teachers, how will we ever get good grades in the exam?”

Because of this, everyone agreed that we needed to act. That’s why we organized ourselves—to make our voices heard by the government and demand that they send teachers so we could continue our education. Our demand was simple: we just wanted the chance to learn.

Royesh: In one grade—say, sixth or seventh—how many classes were there?

Suraya: Each grade level was divided into multiple sections. For example, in eighth grade, there were about 16 or 17 classes in one block, labeled as 1, 2, 3, and so on, up to 16 or 17.

Royesh: So, one grade level, like seventh grade, could have as many as 17 classes?

Suraya: Yes, exactly. It varied. For example, twelfth grade had relatively fewer classes compared to the lower grades.

Royesh: Do you remember the total number of students enrolled at Sayed al-Shuhada in 2021?

Suraya: I don’t recall the exact number, but based on what the school administration said after the incident, there were about 7,000 girls studying there at the time.

Royesh: Was the school exclusively for girls, or did boys also attend?

Suraya: Boys attended classes in the morning, and the afternoon was entirely for girls. Also, younger girls—those in first through sixth grade—studied before noon.

Royesh: And the attack happened in the afternoon?

Suraya: Yes, it was in the afternoon.

Royesh:

When the incident happened, where were you? How did it all unfold?

Suraya:

It was near the end of Ramadan. Everyone was busy preparing for Eid—we were all thinking about the celebrations. That day was supposed to be our last day of school before the Eid holidays.

In our block, we had a separate exit from the other classes. We had just been dismissed when the head teacher came in to collect Fitrana (the charity given before Eid). Every student was contributing to help the school buy materials for new classrooms.

I usually left first because I had a bicycle, but that day was different. Because of the charity collection, we stayed a little longer than usual.

Then it happened—the first explosion.

The sound was deafening. Terrifying. For me, a 12- or 13-year-old girl, and for my classmates, it was something we could hardly comprehend. Living in Kabul, hearing explosions in the distance had sadly become “normal,” but seeing it—feeling it—right in front of your eyes was completely different.

Everyone panicked. The head teacher asked what happened. From the window, I saw smoke and said, “It’s an explosion.” Before we could even process it, the second blast came.

I shouted to my classmates, “Get under the tables and chairs!” I thought if the windows shattered, maybe it would protect us from the glass. But before we could settle, the third explosion shook everything.

By then, almost all the other classes had left. Only ours remained. The head teacher and a few others rushed in and shouted, “Leave the school immediately! There might be another bomb inside—it could go off at any moment!”

We were the last to leave. Because our exit was different, our block suffered fewer casualties. But the students from grades 11 and 12… most of the victims were from their classes. They were the first ones dismissed, and as each block left, they walked past the next—right where the bombs went off.

We were told to take the mountain path to get home, but I had my bicycle, and that made it harder for me to go that way.

When I think of that day, it felt like the Day of Judgment. Everyone was screaming, crying, searching for their loved ones. I kept calling out my sister’s name—she was in grade 11. People told me the victims were mostly from 11th and 12th grade, and my heart sank.

I ran toward the scene. I wish I could erase what I saw. Just minutes earlier, I had been laughing with my friends, talking about Eid plans. Now they were lying there—covered in dust and blood. One had lost an arm, another a leg. There was smoke everywhere, shattered books, torn schoolbags, and pieces of flesh on the ground.

It was one of the hardest days of my life.

Thankfully, my sister and I survived. But I lost so many friends that day—friends with whom I dreamed of a better future. Their only “crime” was wanting an education.

Remembering that day is still very hard for me.

Royesh: How long was the school closed after the attack? When did you return?

Suraya: I think the school remained closed for about one or two months. But even then, there were some students who returned the very next day, saying they wanted to keep studying no matter what.

Royesh: Did you visit the families of the friends who were victims of the attack?

Suraya: Unfortunately, during that month, my sister and I were in a terrible emotional state. We just weren’t able to go anywhere or face anyone. But we did call our friends and checked in on them.

That whole month was like a nightmare. I couldn’t sleep at night. Every time I closed my eyes, I saw the scenes from that day—the blood, the smoke, the bodies. The only way I could sleep was by holding my mother’s hand. Otherwise, I would lie awake all night. It was the same for my sister.

Royesh: Did you ever get official statistics on how many students were killed or injured in the attack?

Suraya: Not exactly. There were media reports and individuals who investigated it, but I didn’t read much myself. My brother told me not to—he was afraid that if I saw those scenes again, my condition would get worse.

But from what we heard in conversations and from what we saw, the number of victims was heartbreaking. Some twelfth-grade classes had 40 to 50 students before the attack—afterward, only a handful remained. That alone shows the scale of the tragedy.

These were girls who were preparing for the university entrance exam, girls who were dreaming of continuing their studies—martyred during the holy month of Ramadan, thirsty, with books still in their hands.

Royesh: Suraya, shortly after this tragedy, the republic collapsed, the Taliban took control, and an incredibly difficult period began—especially for girls like you.

You survived one of the deadliest attacks on Afghan schoolgirls. Then, almost immediately, your entire generation faced another devastating blow: the closing of schools and the loss of basic freedoms.

Yet today, you are strong, optimistic, and full of hope for the future. What helped you get here? How did you find the strength to stand up again after everything? Where did you find that spark to keep going, instead of falling into despair or anger?

Suraya: After the attack, when I was at home, I kept asking myself: Why did I survive? I could have been one of those who lost their lives that day.

And then I realized—there must be a reason I survived. It felt like I was given a mission. A task left unfinished.

When I thought about my friends—those who never got the chance to reach their dreams, who couldn’t continue their education—I told myself: That path is now mine to walk. Those empty notebooks they left behind, I have to fill them.

That thought became my strength. It made me push harder every single day. I studied more, I worked more—because I wanted to do what they could not.

I also look at my mother, who, despite all her strength, never had the chance to go to school. Today, when I see the joy in her eyes knowing that I can be an educated girl, it gives me hope and determination.

I feel there is a gap—an empty space left by my friends who are no longer here. I can never completely fill that gap, but I will try my best. And I hope that one day, I can do more—so much more—to honor their memory and create the future they dreamed of.

Royesh: After the incident, despite the difficult situation, we arranged a scholarship package for Sayed al-Shuhada students and brought a group of girls to Marefat School. Were you among that group? Did you join Marefat?

Suraya: Yes. One of my friends told me about the program and said there were opportunities for Sayed al-Shuhada students. So, I enrolled at Marefat High School and continued my studies there.

Royesh: After Kabul fell to the Taliban, everything changed—especially for girls. How did you adapt? How did you keep your education going under Taliban rule? And when did you first hear about Cluster Education?

Suraya: The fall of the Republic was devastating. Overnight, everything we had worked for in the last twenty years vanished. Girls were stripped of everything—the right to study, the right to choose, the right to decide their own future.

I remember the exact moment I heard the news. I was at home, watching television. The Taliban had just announced that schools would remain closed for girls “until further notice.” That same day, I had been ironing my clothes and preparing my books, excited to start the new academic year.

When the announcement came, it felt like my future was taken away without even asking me. I couldn’t control my tears. I watched girls returning home, sobbing, their dreams shattered—and it broke my heart.

But even then, I didn’t lose hope. I told myself that education doesn’t only happen in school. From that very day, I started studying at home. I reviewed my books, kept writing, and continued learning as if I were in a classroom.

Since I knew some English, I decided to share what I had learned. I began teaching English at courses. Seeing those girls—coming to classes with such enthusiasm despite all the restrictions—gave me strength and motivation to keep going.

At the same time, I was searching for opportunities. I kept applying for scholarships and reaching out to schools and organizations. Because of my connection with Marefat, I knew about the Thirty Birds Foundation. I emailed them, asking if they could support my education.

Thankfully, I received a response—and through that, I joined Cluster Education. That became a turning point for me.

Royesh: What was it like when you first joined Cluster Education? How did it feel to meet other students there? What kind of academic and social environment did you find—and how did the Empowerment program impact you personally?

One of the main goals of Empowerment was to help girls, even in the harshest conditions, hold on to hope and believe in their future. You had faced tremendous challenges before joining the program. Through these lessons on empowerment, how much did you feel your own sense of hope and strength grow?

Suraya: I think joining the Education Cluster was one of the best things that ever happened in my life.

From the moment I joined, I felt the difference. The environment was nothing like the schools I had attended or the other centers I knew. It was warm, friendly, and full of energy. I met new friends, and we supported each other like a family.

The empowerment lessons had a profound impact on me. When we studied those lessons—especially the ones about understanding ourselves—we learned that the “self” is made of two parts: reality and ideal. We were taught to accept our reality, no matter how hard, and then to choose our ideal—the dream we want to strive for.

Cluster Education gave me more than lessons. It gave me a voice. It gave me a community. It reminded me that I am not alone in this world—that there are people who hear us, who work with us, and who move forward together toward shared dreams.

The empowerment lessons—about the self, about turning desires into dreams, and then transforming those dreams into goals, strategies, and actions—changed the way I see life. They taught me responsibility: responsibility toward myself, my community, and the people around me.

Before, I used to think everything should be about me—my success, my future. But through this experience, I learned the power of teamwork. When five people come together with one shared purpose, they create a force strong enough to make real change happen.

Royesh: As part of the Peace on Earth game, you took some remarkable initiatives—like educating women in your community. During this process, you reached out to mosques, spoke with religious scholars, and worked with local elders. How did this idea come to you? Was it your first experience engaging with religious leaders? And how did people react to this effort?

Suraya: When we formed our Peace Group, we named it the Solh Group—which means “Peace.” There were six of us working together. We agreed that whatever we did should not just benefit us personally; it had to create a real impact on our community—something meaningful, something that would last.

After several discussions, we came up with an idea: “Let’s help our mothers become literate.” Because in a family, a mother is like a leader. When a mother is literate, the whole family becomes stronger.

We partnered with another group and formed an association called Hamdelī—meaning “Empathy.” Our mission was to create learning opportunities for mothers and for girls who had been deprived of education under the Taliban.

We held several planning sessions and decided to start from the mosques. If schools were closed, then why not turn mosques into schools? Why not turn homes into schools? We divided tasks among ourselves and began reaching out to local mosques and religious scholars to seek their support.

At first, it was hard. Some mosques refused to cooperate. They suspected we had another agenda and couldn’t understand why we wanted to teach for free. But we didn’t give up. After many conversations, we finally found one mosque that agreed to work with us. Even then, the discussions weren’t easy—they had a lot of questions, some unrelated to our work, and their expectations were very high.

We explained again and again that our only goal was education—so that mothers could learn to read and write, and so that we, as girls deprived of formal schooling, could share what we had learned. Eventually, they agreed. I think their own level of education helped them understand our intentions.

When we announced the program, the response from mothers was incredible. On the very first day, which was our opening session at the mosque, about 60 mothers came and registered.

It was one of the most beautiful experiences of my life—watching mothers, despite all their hardships, come with such enthusiasm to learn. They practiced writing on the board, shared their stories, and little by little, they began to change.

Many of these women had been afraid to speak about their lives. But in the mosque, they grew stronger and more confident. We weren’t just teaching them the alphabet—we were sharing the same empowerment lessons we learned in our program. We taught them that they, too, could dream, and that literacy was the first step toward that dream.

That experience taught me that change begins with small steps, but those steps can transform lives.

Royesh: Over time, how many students did your literacy program reach?

Suraya: We organized two separate sessions so that mothers could come and study at different times. In total, our program reached about 150 to 180 women.

Some of them were in their 70s and even 80s—and yet they came, eager to learn, despite all their hardships. I remember how they used to say, “When we come here to learn, we forget our pain, our high blood pressure, and our worries. We just feel happy.”

For me, that was one of the most rewarding parts of this experience—seeing how education brought not only knowledge, but also joy and dignity into their lives.

Royesh: You sent us a few videos of mothers—some of them 70 or 80 years old—sharing their feelings. We’d love to hear about that experience directly from you. For example, one mother said, “My blood pressure has been controlled since I joined these lessons,” and another said, “My eyes have opened here.” How did they describe what they felt? What was it like to see women of that age come to the mosque, learn to read, and even enjoy reading the Quran?

Suraya: In the beginning, they were shy about being filmed, but over time, as we built trust and spoke with them warmly, they became comfortable. Our conversations were always like those between a daughter and a mother. They opened their hearts to us.

Almost every mother told us that her greatest regret was not being able to study when she was younger. They all said their biggest dream was to read the Quran for themselves. That desire brought them to us—and they came with incredible determination.

The first time they wrote words like “mother” or “daughter” on the board, their faces lit up with joy. It was a powerful moment—proof that learning has no age limit.

I managed the sessions and visited regularly, sometimes weekly or every two weeks, to check on their progress. From the moment we arrived until we left, they would shower us with prayers and blessings. They always said, “May God bless you, may you succeed in life.” I truly believe that their prayers are one of the reasons we’ve achieved what we have today.

Royesh: You mentioned the Hamdelī Association earlier. How many people were involved in leading this program?

Suraya: Two Peace Game groups came together for this initiative. In total, there were eleven of us—six from our group and five from the other. We planned everything carefully from the start, assigning roles for management, instructors, and coordination so the program would run smoothly. That teamwork was the key to moving this effort forward successfully.

Royesh: During these programs, you must have faced some expenses—like buying a board, markers, and stationery. How did you manage those costs? Who supported you?

Suraya: Our program was entirely grassroots. The eleven members of the Hamdelī Association—eleven girls who themselves had been deprived of education and wanted to help their mothers and sisters—started it without any external support.

We didn’t receive funding from any organization or individual. The lessons were completely free for the students. For supplies like boards and markers, we pooled money from among ourselves. During our weekly sessions, instead of paying instructors a salary, we agreed that everyone would contribute toward buying what was needed. Sometimes, when our students made great progress, we even bought small gifts for them—all from our own pockets.

Royesh: During the Peace Game programs, you carried out impactful activities, but since these efforts were mostly personal and community-based, we may not have been able to highlight them fully. However, you received an international award for peace. Tell us about that award. How did you become involved, and what opportunities did it bring?

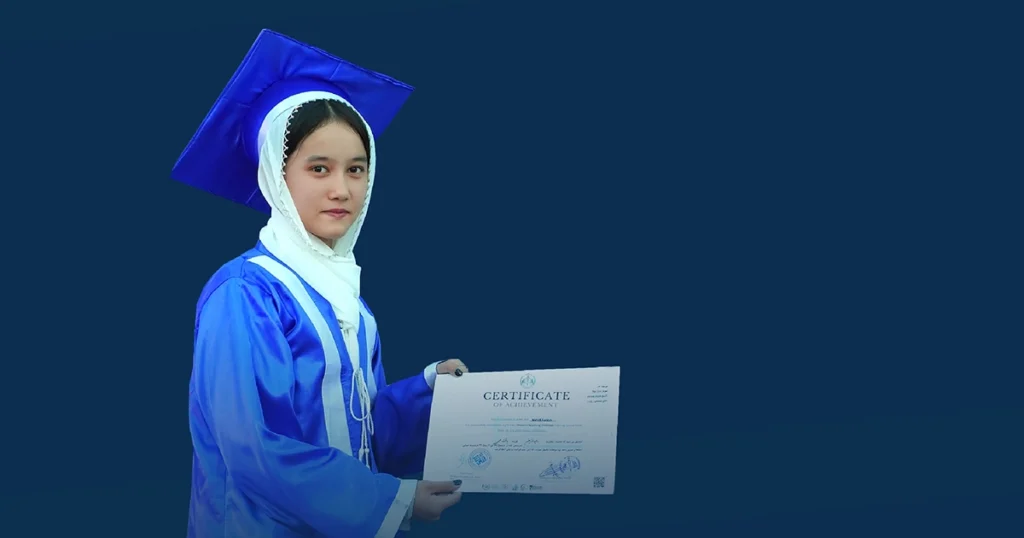

Suraya: Yes, in recognition of our literacy programs and Peace Game activities, we were nominated for the Wilson Hinkes Peace Award by Cluster Education, with the support of Dr. Farzin.

In 2024, I was honored to receive this award along with three of my colleagues from Cluster Education. Winning this award was not just an achievement for us personally—it represented the dedication and resilience of all the girls involved in the Cluster Education program.

This recognition gave us renewed motivation to keep going and inspired us to expand our impact. It showed us that even small efforts, when rooted in hope and teamwork, can be seen and valued by the world.

Royesh: When it was announced that you had won the award, you also joined an online event. What was the most important message you shared with your international audience?

Suraya: Yes, on October 17th, we participated in an online meeting where we were introduced as the winners of the Wilson Hinkes Peace Award. Many friends from the organization were present, along with Dr. Farzin, you, and others.

The message we shared was simple but powerful: Afghan girls still exist. We are still here.

Despite all the challenges and restrictions, we continue to strive, to hold on to hope for a better future. And, God willing, one day we will overcome all these obstacles. We wanted the world to know: We are here, and we will remain.

Royesh: Not long after this experience, you left Kabul and moved to Pakistan. What led to that decision? Was life in Afghanistan too difficult, or was it about finding educational opportunities?

Suraya: Migration is never easy. Leaving behind your home, family, and friends can be one of the hardest decisions in life. But for me, it was necessary.

After the award, I stayed in Kabul for a short while, but with the Taliban’s restrictions, I could no longer go to school. My family saw me sitting at home, unable to study, and they couldn’t bear it. Education has always been a dream for me—and for them.

So, we made the difficult decision to move to Quetta, Pakistan, because here, girls have relatively better opportunities to continue their education. It wasn’t just a move—it was a sacrifice for hope, for the chance to keep learning.

Royesh: Now that you’ve come to Quetta, you’re still part of the Cluster Education programs and have continued your activities with your friends and group members. What differences do you notice between the environment here in Quetta as a migrant girl and the conditions you had in Afghanistan?

Suraya: Honestly, I can’t say that the situation here is perfect—migrants face certain restrictions that limit their progress. But compared to Afghanistan, there are relatively more opportunities here for girls who want to move forward.

Back in Kabul, despite all the limitations, we carried out our activities. But here, if a girl truly wants to continue her education and work, there is a bit more space to do so.

Of course, this also depends on mindset—on how one views challenges and opportunities. Personally, I didn’t want to lose any time. The day after I arrived in Quetta, I joined Cluster Estiqlal and resumed my lessons because I refused to fall behind again.

We’ve also formed a group here called Peace Ambassadors, and our activities are ongoing. We do whatever we can within the resources available to us, and above all, we try to be the voice of those girls who are still silenced back home.

Royesh: You’re among the girls who, in addition to activities in the Peace Game and women’s education, have also been active in writing circles—both writing your own pieces and helping others develop their skills. How much of your work has been published so far?

I’ve heard you’ve prepared a collection of your writings to be published as a book. How many pieces will be included? What has writing meant to you, and what have you learned from it?

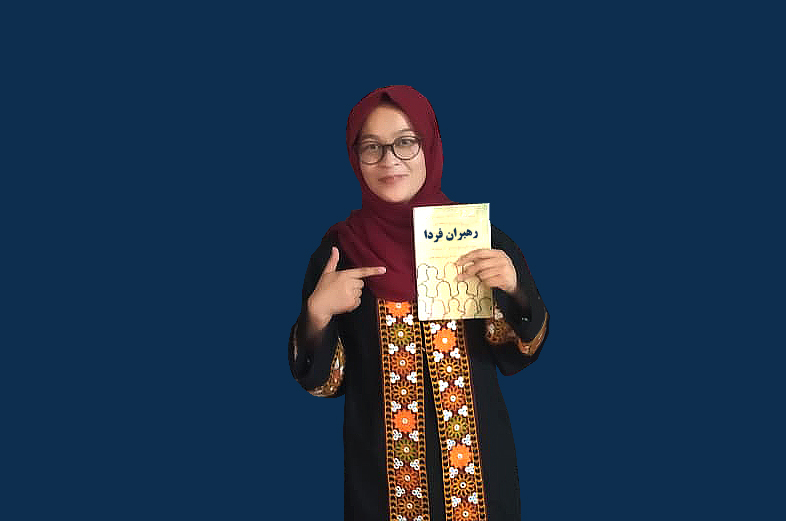

Suraya: My writing journey began after the fall of the republic. The very first piece I wrote was about the Sayed al-Shuhada School attack. When I saw how much encouragement I received from my family, teachers, and friends, it motivated me to continue.

Since then, many of my writings have been published in both Afghan and international platforms—Sheesha Media, Rokhshana Media, 8 Sobh, and others. So far, I’ve written nearly 50 pieces, and I’m preparing them as a book for present and future generations—a book that will help people understand what life means for a girl in Afghanistan, and how a girl, deprived of everything, can still rise again and move forward.

Many of my friends in Cluster Education are also writing about their daily lives, their struggles, and their dreams. Writing, for me, is powerful. It’s more than an art—it’s a form of resistance against silence. It allows us to express what we cannot always say out loud and to make our voices heard in the world.

I’m so happy to be part of this space, to learn from my friends and from you. God willing, I hope we can become good writers in the future and keep this voice alive.

Royesh: In the Empowerment program, there are specific exercises—like keeping a daily reflection journal where you write at least five thought-provoking points each day. Did you practice this regularly?

Suraya: Yes, in Kabul we tried to do this exercise regularly because it was so impactful. Writing reflections helped us change our mindset and gain new perspectives on life.

Personally, I kept notes whenever I attended programs, meetings, or online sessions. I began to notice how different my way of thinking—as a girl born in Afghanistan—was compared to girls born in the U.S. or Japan. I wrote these observations down and reflected on them deeply.

Even after migrating, I still write daily reflections—especially on the lessons migration teaches us. I note down what I learn and then try to apply those lessons in my own life.

Royesh: Among the people you met through Empowerment programs was David Gershon, the founder of the Empowerment movement and the Peace on Earth Game. For me—and for you—he’s both a mentor and a coach. What was it like meeting him?

Suraya: It was an incredible experience. I attended many online sessions with David Gershon, and we even participated in Peace on Earth Game circles with him. Speaking with him was always inspiring.

What struck me most was how warmly he welcomed our ideas. People from all over the world were sharing their activities during these sessions. At first, I thought their actions were simple compared to ours. But when we shared our own experiences—and they embraced them with such enthusiasm—it made us proud. It felt good to know that our efforts mattered, and it motivated us to keep going. God willing, we’ll continue these programs with him in the future.

Royesh: The Peace on Earth Game also includes some unique exercises—like passing energy in a circle, or looking into your own eyes in the mirror and affirming your strength. Do you have a personal memory of doing these exercises—something that left an impact on you?

Suraya: Yes, one of the most beautiful exercises is standing in front of a mirror and looking into your own eyes. Every time I do this, I feel something powerful inside me.

When I look into my own eyes, I tell myself: “Yes, you can become strong. You can make a difference in your society.”

The dreams we talk about today—the hopes we have for one day—when I look at myself, I believe they can come true. I tell myself: “These are not ordinary eyes. They are the eyes of someone who can create real change.”

This practice fills me with energy and faith in my potential. It makes me believe that one day, I can help others and make an impact. And I also hold on to the hope that the situation we live in today—where girls are deprived of their basic rights—will not last forever.

It’s such a powerful exercise, and I believe anyone who tries it will discover new strength within themselves.

Royesh: In one of our Empowerment sessions, you shared a special interpretation of your name. Would you like to share that again with your audience?

Suraya: Yes, it was during an Empowerment session with international guests. I wanted to say something unique and meaningful, so I decided to share what my name means.

From what I’ve learned, Soraya means “a cluster of stars in the sky.” It can also be interpreted as a chandelier.

When I think about that meaning, I feel it reflects my identity and the kind of work I want to do. A cluster of stars represents light, guidance, and hope—and that is what I aspire to be.

Right now, and in the future, I want to become that light—a star who brings hope to others, supports them, and helps them in ways that truly impact their lives.

Royesh: In the Girls’ and Women’s Empowerment Program, we work with key concepts like Women’s Power, Women’s Leadership, and Women’s Perspective. What do these mean to you? When you think deeply about them, what special feelings do they create—and how do they shape the vision you want to share with your society, or even the world?

Suraya: When we talk about women’s power, we’re talking about a special kind of strength that is often ignored in our world.

In our empowerment sessions, when we think about women’s leadership, the image that comes to mind is a mother. A mother is the first leader in any family—she sacrifices for everyone, keeps the family united, and never discriminates between her children. She nurtures, she protects, and she loves unconditionally.

And this is why we believe that if a country were led by a woman, there would be no war or violence. Because a mother, by nature, does not destroy—she builds. She does not kill—she gives life. She does not divide—she unites.

If women were in leadership positions, the problems we see today—war, hatred, discrimination—would not exist. Because women lead with empathy, with care, and with the vision of a family that lives in harmony.

I believe the world needs this kind of leadership now more than ever. And in Afghanistan, I am 100% certain that if women lead, the future will be brighter than what we have today.

Royesh: At one point, you said that when a woman commits violence, she is repeating a masculine experience rather than expressing her true feminine nature. What did you mean by that? Do you believe that violence is incompatible with femininity, and if a woman becomes violent, is it because of her environment rather than her essence?

Suraya: Yes. Some qualities are natural, and kindness is deeply rooted in a woman’s nature—especially in a mother. Women are inherently nurturing; they are not aggressive by instinct.

Unfortunately, it’s often harder for men to control aggression, and history shows that violence has been a masculine expression of power. Of course, there are men who are loving and peaceful, but generally, a mother’s essence is care, compassion, and protection.

So when a woman becomes aggressive or violent, it usually means her environment has deeply influenced her. By nature, a woman does not seek to harm—she creates, she sustains, and she protects. That is why women’s leadership is so critical: it brings those qualities into spaces where violence currently dominates.

Royesh: What would you say is one of your most successful experiences in the past two or three years—something that created real change, but without pressure on yourself or others?

Suraya: I think our work with Cluster Education has been one of the best examples of peaceful change. In these years, everything we did—whether studying in the cluster or organizing literacy programs—was carried out with care.

We worked in ways that didn’t create problems for anyone, even in a difficult environment like Kabul. For example, our literacy programs in mosques were carefully planned so they wouldn’t draw unnecessary attention or cause tension in society.

That’s something I truly value: girls taking responsibility for their work while ensuring it benefits the community without creating conflict.

Royesh: Now, imagine yourself twenty years from now. The small groups of five you’re creating today have multiplied into thousands. Each one is spreading light, awareness, and peace—without force or pressure. And you’re still there, continuing your mission. What kind of world do you see? Describe the vision you hold in your heart.

Suraya: I’ve shared this vision before in empowerment sessions, and it never changes:

If we keep going as we are—if we continue these programs—the world twenty years from now will look completely different. I see a society free from violence, free from war, and free from discrimination. A society where no one is judged by gender, where everyone lives under the shadow of peace.

Girls will return to schools. Women will lead countries. And because of their leadership, the world will experience something entirely new—a society built on empathy, equality, and justice.

I believe the future will belong to peace, and I believe women will lead that transformation. When that day comes, life will be beautiful for everyone, a life where all people have the right to dream and the chance to make those dreams real.

Royesh: Suraya, your real journey in life began after surviving a deadly explosion—the horrific bombing at Sayed al-Shuhada School, where hundreds of your peers were killed or wounded. For almost a month, you couldn’t even imagine talking about it or revisiting the news. But now, nearly four years later, you stand here with strength and clarity.

Today, the Taliban control your country. They continue to strip women of their rights, their voices—even their lives. As someone who survived that tragedy, someone who now lives under a system that denies girls education, I want to ask you: Do you hate the Taliban? Do you see them as your enemy?

And let me frame this honestly: Afghanistan’s history is full of cycles of eradication. The PDPA said they would eliminate the “Al-Yahya” group; the Mujahideen came and wiped out the communists; the Taliban came to destroy the “corrupt Mujahideen”; the Republic tried to defeat the Taliban—and now the Taliban are in power, erasing women from public life.

One day, if you come to power—if you establish the society you dream of—what will you do? Will you eradicate the Taliban as others did before you? Or will the world you imagine—the world where you shine like a star—also include the Taliban, but a different kind of Taliban?

At your age, just 16 or 17, how do you honestly feel about them?

Suraya: Despite everything the Taliban have done—despite banning girls from education and taking away women’s most basic rights—I do not hate them. I don’t see them as my enemies.

I’ve always said this: I see the Taliban as people who need my help—people I need to help understand that what they are doing is wrong. This is not the right path. They need to change—and we need to help them change the way they see the world.

In the future, in the kind of leadership we envision, the Taliban will not be eliminated—but they will not be the Taliban of today. They will be people who take their daughters to school, who value education, and who respect human rights and human dignity.

When we talk about leadership, it does not mean killing or eliminating those who have wronged us. That is not what female leadership stands for. Female leadership is built on goodness, not revenge.

And it’s also not about sidelining men or taking away their rights. Absolutely not. It’s about equality—equal rights for all. In the leadership we dream of, people will not be judged by their gender, but by their character, their talent, and their ability to contribute.

I truly believe the Taliban can change—if they stop being puppets and choose to be themselves. I hold no hatred, no resentment. I simply believe they need help, and it is our responsibility to help them.

Royesh: This might be my last question, Suraya Jan—and I hope you’ll answer it with the same sincerity you’ve shown throughout.

You’ve seen so much pain—violence, hardship, and unkindness. Life has often shown you its harshest face. So I wonder: what is your connection to joy, to laughter, to music, to dance? How much do you see yourself as a joyful girl? How much do you believe this world becomes more beautiful with laughter?

Has life’s bitterness stolen some of that joy from your soul? Or have you managed to preserve joy as the spirit and meaning of life within you—just as you’ve preserved hope in so many other ways?

Suraya: Despite all the pain and bitterness I’ve experienced, I have tried never to forget joy. I believe joy and sorrow are both essential parts of life. You cannot imagine life without one or the other—they exist side by side.

Yes, there are days when sorrow feels heavier than anything. But as much as possible, I’ve tried to find reasons to be happy—because life is too short not to.

My family and friends have always supported me, and if there is a Suraya today who can smile despite everything, it’s because of them. For their sake—and for my own—I’ve tried to live a life where happiness still has a place.

We only get this chance once. Life comes only once. So let’s live it fully, let’s laugh, let’s smile—even when problems surround us. Because problems will always be part of life, but so can joy.

I’ve learned that even a single moment of happiness—shared with others—can make life meaningful. So despite everything, I choose joy. Because that’s life: a blend of sorrow and laughter, of darkness and light. And in that mix, we can always choose to keep smiling.

Royesh: What is your final message—something from your heart that I didn’t ask, but you’d like to share?

Suraya: My final message is for all the girls of Afghanistan—those who are currently deprived of their rights, whose voices have been silenced. I am one of you. And to my sisters I say: failure exists in life, but failure is not the end. I truly believe failure is a step toward success.

Whenever we face problems or encounter limitations, we must not allow them to weaken us. On the contrary, these challenges should make us stronger.

Yes, today’s circumstances are harsh. But even now, each of us can take small actions—simple steps every day—to transform our lives. One thing I strongly recommend is reading. Books have had a profound impact on my life. If you have books at home, read them; if you can access resources online, take advantage of them. Knowledge is power—and it’s something no one can take from us.

I also have a message for the Taliban: What you have done so far is enough. Please, pause and reflect on your actions. You still have an opportunity to change—to become better human beings. Use this chance before it’s too late.

And to those who call themselves defenders of human rights: the current situation in Afghanistan is unacceptable. Half of society—its women—has been erased from public life. This is a violation of basic human rights. We call on you to take real action.

Finally, to all Afghan women: never wait for someone else to come and save you. We must save ourselves. Through small, consistent efforts, we can transform our lives and achieve the beautiful dreams we hold in our hearts.

I hope this dark chapter ends soon. I hope Afghan girls regain their equal rights and take their rightful place in building a better society.

Royesh: Thank you, Suraya Jan. We will be waiting for you—23 years from now—when Suraya at 17 becomes 40 and presents to the world a new model of leadership: women’s leadership!

Suraya: Thank you so much, Ostad!

Comments (0)

Leave a Comment