FutureSheLeaders (11)

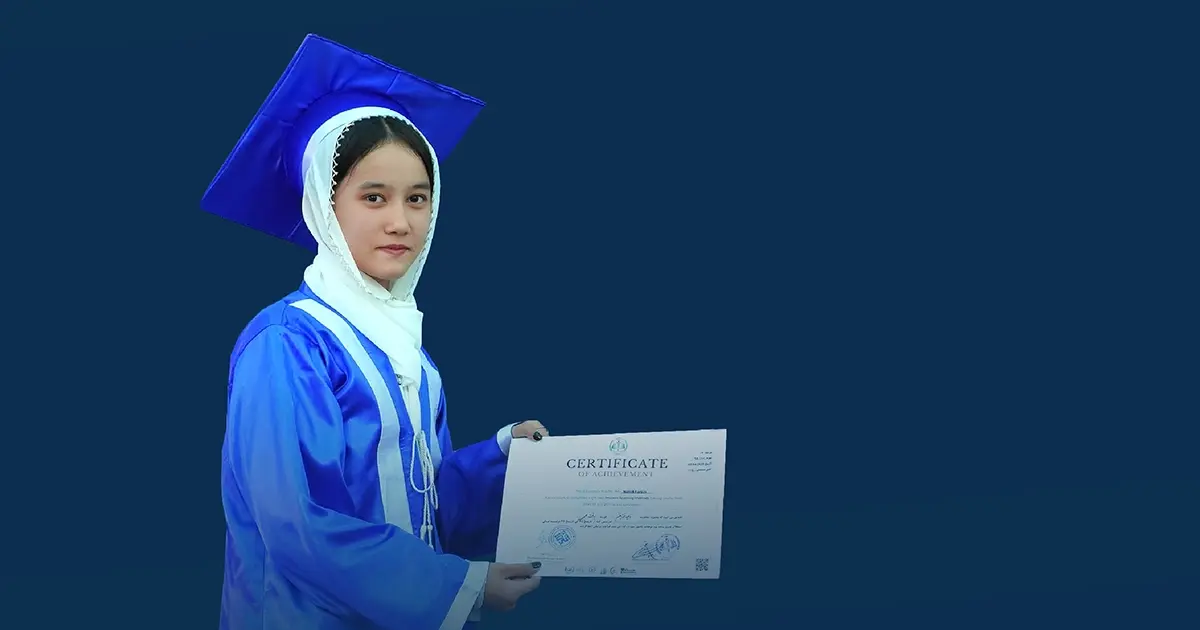

This week, we listen to the story of Parvin Yavari – a young woman who has walked a path carved through the hardships of displacement, exile, and the pain of being labeled a “foreigner.”

From the moment she was just five, when a boy in the park shoved her off a swing and shouted, “Go away, Afghani!” to the day she rose to become an Olympiad champion, earned a scholarship to Italy, and traveled to New York and Washington for a global leadership program — Parvin has embodied the quiet, powerful miracle of “woman’s resilience”.

In every “no” she was given, she planted a seed of hope — and from the shadows, she found her way to the stars.

This is not just the story of one girl — it’s the story of faith, perseverance, and the will to rise.

Let us listen to this beautiful and inspiring journey in Parvin’s own words.

Royesh: Dear Parvin, hello. A very warm welcome to the “Leaders of Tomorrow” program!

Parvin: Hello, Mr. Royesh. Thank you for inviting me. I’m happy to be here and also send my greetings to everyone watching this program.

Royesh: How did you find out about the “Leaders of Tomorrow” series? And what made you interested in being someone who presents her leadership model—a different way of living—for your generation?

Parvin: I’ve always been aware of your work and the activities of the Ma’refatSchool students, but I specifically learned about this program from my dear father. When I was applying for the Young Leaders Program in New York, he told me that Mr. Aziz Royesh’s activities were aligned with that field. After that, I got more familiar with this program.

Royesh: You mentioned your educational trip to New York, and now you’re in New York and Washington. Can you tell us how you got from Italy to this journey?

Parvin: It was a program you had to apply for. I live in Italy in a student residence that has its own associations and structures. These residences are merit-based and offer special programs to their students, and this program was one of them. There was only one scholarship available for it, and you had to compete. Fortunately, I ranked first among the applicants, so I was able to join the program and come.

Royesh: What was your first reaction when you saw your acceptance letter to the New York leadership program?

Parvin: It was a bit unbelievable to me. Because in order to be accepted, you had to be eligible. I was eligible in many aspects, like having a good level of English and relevant experience. But because I was from Afghanistan—and it was clear that traveling from Italy to New York, especially with the recent regulations—made me feel they might not choose me. The choice might have seemed a bit irrational, as it was possible I wouldn’t be able to go. That’s why it was a mixture of happiness and surprise.

Royesh: What changed in your perspective on leadership through the program you participated in?

Parvin: Before this, I always thought a leader is someone who is always with their team and is humble. But what I learned in this program was, first of all, we have different leadership models, and these models can vary depending on the place and type of job. These models explain the leadership process. But we also have leadership styles. A leadership style is more personal and refers to an individual. A leader can have their own style while adopting different models depending on the situation and time.

Royesh: In your biography, I read that you were a child when you left Afghanistan. You probably don’t have a vivid memory of Afghanistan—Kabul, Ghazni, or wherever you were born—but surely your family has spoken about these places. As a girl growing up in migration, what mental image do you have of Afghanistan and Kabul?

Parvin: As you said, I’ve had very little direct experience in Afghanistan. But in our family, we always talked about Afghanistan, and that helped me form a mental image of it. Kabul, for me, is a symbol of resistance—especially with the recent events. Whenever I think of Kabul, the word “resistance” comes to my mind.

Royesh: Now that you’ve come to New York—having already seen Rome and previously Tehran—and since you also have a mental image of Kabul, when you compare them, what similarities and differences do you see?

Parvin: The similarity between Tehran, Rome, and New York—even though New York is not the political capital—is that capitals are generally busier, and life is more intense there. People live with more urgency; stress levels are higher. But in terms of differences, there are major cultural differences. Each city has its own story, its own identity. Architecturally and in many other ways, they are different, and that creates a unique image for each person.

Royesh: What is the biggest lesson you’ve taken from New York as a young woman?

Parvin: The first time I walked around the streets of New York, the one thing you can’t ignore is the buildings and skyscrapers. Then I had the chance to go to the top of one of the towers, and from there, you could see the whole skyline—New York from a 360-degree perspective. Before that, when you look at a building like the Empire State, you think, “Wow, how big and tall!” But when you’re looking at it from the top of another tall building, you realize how small it looks—and that there are even taller ones. That taught me how much our perspective can change the way we view problems. It was like confirmation for me that our viewpoint deeply affects how we see challenges, and it’s always better to consider multiple angles when facing life’s difficulties.

Royesh: New York is the business capital of the world. At the same time, you see people, colors, and cultures from all over the globe. As a girl with Afghan roots, who has lived in Iran and has an experience in Italy—how did you feel being in the midst of New York’s diversity?

Parvin: First of all, I’ve always seen myself as a girl from Afghanistan—and I still do. Unfortunately, in Iran, because of the conditions that always exist, you live, but you don’t feel a sense of belonging. I haven’t been in Italy for very long either, so that feeling hasn’t formed yet, even though I’m trying to engage with the community more. In New York, I wasn’t there for long—just a few days—but I felt a sense of comfort. You could be among hundreds of different colors and people, and being different wasn’t something that stood out; it was normal.

Royesh: New York is a fast-paced city. People move quickly…

Parvin: They talk fast too.

Royesh: …they talk fast. Even the images on the walls move rapidly. Everything is in motion. As a girl immersed in this hustle and bustle, what other feelings did you have?

Parvin: Italian culture is quite mellow. When someone is really active, people there find it strange. But in New York, it’s the opposite. So I felt that in this place, being active makes your presence more visible, and I felt like that energy in the city aligned with the energy inside me.

Royesh: From here, I want to take you back to your past and follow your life’s path from your birth and childhood. Could you tell us when and where exactly you were born?

Parvin: When we came from Afghanistan to Iran, we brought nothing with us financially—just ourselves. The first few years were very difficult. We had to live with other families and could only afford to rent one room in a house. But through the hard work and efforts of my parents, we were able to get our first independent home in a short time. That’s always been a turning point in my life. When I migrated to Italy, I had to start from scratch again. But I kept telling myself: “Your parents started from zero—maybe even below zero—with four children. So you can definitely start over too.”

Royesh: It would be good to hear more about your parents—their names, their education, and what they did to build a life where their daughter could eventually make her way to Italy.

Parvin: My father is Mr. Ali Yavari, and my mother is Ms. Rahima Mohammadi. When we came to Iran, like most Afghans—as everyone knows—we had to do hard labor. My father worked in construction. My mother stayed home to care for us, but she also did handicrafts to contribute to the household income. Initially, we mostly relied on my father’s income. My parents don’t have formal academic education, but they are both literate and well-read. My father reads a lot of books, and I think my love for reading started because I always saw him reading whenever he wasn’t working. Their habit of reading made them more knowledgeable than some people who only have academic degrees.

Royesh: As the eldest child in your family, how would you describe your childhood in just a few words?

Parvin: I have a lot of good memories from my childhood, especially with my father. He wasn’t home much because he had to work a lot—sometimes only coming home a few times a month—but whenever he did, he tried to play with us and even influenced how we played. For example, he once built a microphone out of Lego and told me, “You’re a TV host—say whatever you want.” My sister would be the reporter. In my imagination at six years old, I was a world champion skier. All these games laid the foundation for the person I am today—and for my siblings too.

Royesh: Is it hard for you to recall the time when you were just four years old and left Afghanistan? Do you have any faint memories of it?

Parvin: I remember only one thing—a water channel in front of our house, with cool, clear, flowing water. The whole area we lived in was known for its good water.

Royesh: Do you remember the first time you realized you were a refugee from Afghanistan, living in another country—what did you feel?

Parvin: Up until I was five, I didn’t know there were differences in nationality. One day at a park, I was on a swing—it was my favorite thing—and I was trying to go as high as I could when a boy pushed me from behind and shouted, “Get lost, Afghan!” He was a bit older than me, bigger. I didn’t even know what “Afghan” meant. I could just tell from his tone that it was something bad. That night at home, when my dad came back from work, I was still thinking about it. I asked him, “Dad, what does Afghan mean?” He paused for a moment and then asked why I was asking. I told him what had happened, and he explained to me that we’re from Afghanistan. In Iran, people from Afghanistan are called “Afghan” or “Afghani,” and unfortunately, people here look down on us. He told me: “They may see us as less—but you should be proud to be Afghan.”

Royesh: Today, your personality has developed a lot. How do you think your parents influenced who you are?

Parvin: My parents had the greatest influence on who I am today. I believe I am the product of their thoughts and upbringing. They were my first references in life, and I have to say they had a profound impact on me.

Royesh: Can you name a specific quality you learned from your mother—something in her words, behavior, or how she handled life?

Parvin: What I learned—or tried to learn—from my mother is patience, loyalty, and hard work. There were difficult times, especially in our early years in Iran, but my mother stood alongside my father and did everything she could to improve our lives.

Royesh: What about your father—what’s the most important influence he had on your character?

Parvin: I think the persistence I have today comes from my father. And another key trait—refusing to accept “no.” There were many times, like when I was 7 and supposed to start school, but due to Iranian laws, I wasn’t allowed to enroll. My parents—especially my dad—worked so hard to change that. I couldn’t start first grade at 7, but if it weren’t for their relentless efforts, I probably wouldn’t have entered the school system at all.

Royesh: Was there ever a time in your childhood when someone told you that you couldn’t do something—and you proved them wrong?

Parvin: Yes. The Iranian education system is structured in a way that you study for 6 years, then 3 years, and then another 3 years. In the second cycle of 3 years, you switch schools, and the grading system changes too. In the first 6 years, grading is by letters: A, B, C, D. Then it switches to numerical scores out of 20. When you get an A, you don’t really know if you scored 19 or 20. When I was about to enter grade 7—middle school—I said I wanted my average to be 20 out of 20. One of the eighth-grade students told me, “That’s impossible. Even if you get all 20s, the teachers won’t give you a 20. Don’t expect that from yourself or you’ll be disappointed.” But I not only finished grade 7 with an average of 20, Idid the same in grades 8 and 9 too.

Royesh: Migration comes with many difficulties—especially for a child whose first experience with it was through an insulting comment like “Afghani,” accompanied by an act of aggression. What is the hardest moment from your experience of migration in Iran that you remember?

Parvin: Life as a migrant in Iran had its ups and downs. Personally, the hardest parts were related to my schooling. I didn’t attend first grade because the law didn’t allow it at the time. I started grade 2 halfway through the year, after receiving a special educational permit known as the “green sheet.” School had already begun, and finding a place was very difficult. In grade 3, I was expelled in the middle of the year. Sometimes I would attend, but like a ghost—unofficially. I only went to school for one month in grade 4, and that too came with many challenges. I had to take the grade 3 exam, and none of the teachers wanted to accept me in their class. They thought a student who had barely attended school couldn’t catch up in a month. They didn’t want to lower their teaching standards. I properly started school again from grade 5. In grade 6, I wanted to apply to a school for gifted students, but I wasn’t even allowed to sit for the exam. In grade 9, I found out there was such an option again and spoke with the local education office and school principal. They eventually cooperated. It was tough; I was told “no” many times. But in the end, I think everyone in the local school system knew me—they always said, “Ms. Yavari is back.” I got the permission, I took the test, and I had studied hard for it. But then I learned that they didn’t even review my test paper. They saw I was persistent and refused to accept “no,” so they pretended to agree—but then ignored my work anyway.

Royesh: In such difficult circumstances, often the only thing that can carry someone through is a single thread: “the thread of hope.” As a girl, again I ask—what truly gave you hope and helped you keep going?

Parvin: To be honest, this happened when I was in grade 9 and about to move on to grade 10, which also meant switching schools. It was a very difficult experience for me. Processing it emotionally was hard. Maybe now it doesn’t seem so serious—even to me—but for the 15-year-old Parvin, it was very painful. I remember I didn’t want to go to school anymore—not because I didn’t want to learn, but because I didn’t want to go to that environment. At first, my father didn’t say anything. But later, he spoke to me logically and convinced me to return to school. I think in those moments of despair, the presence of my parents and siblings was a great support. When I decided to give up, they didn’t let me.

Royesh: Sometimes we form emotional attachments to certain items in our life—like a school uniform, notebook, pen—something that connects us to the past. These things begin to speak to us. Have you ever spoken to such an item, like your old school uniform or something else that evoked memories?

Parvin: When I was 5, I started learning the Persian alphabet. My first teacher was my father—he taught me whenever he had time. Since I always loved school and being a student, they had already bought me a school uniform and a backpack. When I wasn’t allowed to go to first grade, I would still wear the uniform and hug my backpack. Sometimes I’d watch other girls walking to school.

Royesh: Often people find themselves confronting their own reflection—sometimes they give themselves a score, sometimes they compliment themselves, sometimes they criticize. What do you feel when you stand in front of a mirror? What image comes to your mind?

Parvin: That’s a very tough question, Mr. Royesh. Honestly—and I say this humbly—when I think about my past, the one word that comes to mind is “confidence.” I feel like one of the main reasons I’ve reached this point is because I’ve had self-confidence. When others thought I couldn’t do it, I always tried to first identify the problem at each stage, then find a solution specific to that stage. When I look in the mirror, I see a girl who has made many mistakes along the way, but has tried to learn from all of them. I hope that when people think of me, the word “confidence” is tied to the name Parvin.

Royesh: Has it ever happened that, while looking in the mirror, you thought someone else your age might be somewhere else, seeing your situation and feeling envious—thinking you are much luckier?

Parvin: Yes, definitely. Many times. During high school, I had classmates—Afghan girls like me—who worked just as hard as I did, and some were probably even more talented. But the support my family gave me for my education, and how much my decisions mattered to them, wasn’t something they had. I realized how fortunate I was in that regard. Later, when I came to Italy and found myself sitting in classrooms where sometimes I wasn’t just the only Afghan, but the only girl, I realized I was in a place many others wished they could be. That awareness gave me a sense of responsibility—to appreciate every opportunity and make the most of it.

Royesh: In a competitive academic environment—especially as a migrant—surely you encountered rivalry, and maybe even discrimination. Have you ever experienced humiliation or insults from classmates or others at school?

Parvin: Unfortunately, yes—especially back then. I think things are a bit better now. There were very few Afghan students in school, and teachers and administrators saw Afghans as foreigners. Since I had grown up in Iran, I spoke fluent Persian with an Iranian (Tehrani) accent. There were times when a teacher, after three months, would realize I was Afghan and say, “You don’t look Afghan at all.” That shows how people stereotyped Afghans—you could supposedly spot them at a glance. Before they knew, they treated me normally; after they found out, their behavior could change. There were definitely moments of humiliation—but how we respond is just as important. I remember once we had a class competition and our group—which was mostly Afghan students—won. Afterward, one of my classmates wrote some unpleasant things on the wall next to where I sat. I noticed it two days later. During one class, the teacher gave us five minutes of free time at the end, and I asked if I could say something. I told the class: “If you have a problem with me, just come talk to me. Writing things on the wall isn’t right. If there’s an issue, let’s address it face to face.” That really caught the teachers’ attention. Later, I had a meeting with the school principal too. And in one of the school’s morning assemblies, where administrators usually speak before classes start, they addressed the issue and said: “All students are equal. Until you prove you’re more capable, there’s no superiority based on race or nationality.”

Royesh: The school you attended in Iran was certainly an all-girls school, given Iran’s specific regulations.

Parvin: Yes.

Royesh: During your school years, did you ever have any interaction with boys? Was there any opportunity to compete with or engage in activities with students—boys—from other schools?

Parvin: When I was in 11th grade, I participated in a student Olympiad—if I recall correctly, it was on stem cells and regenerative medicine. There was a preparatory class before the second phase of the exam, and I was the only girl in that class. Because I was the only girl, they didn’t arrange a separate class for girls, so all of my classmates were boys.

Royesh: How did you feel when, for the first time, you found yourself in a classroom full of boys—transitioning from the safe space of an all-girls environment into a male-dominated setting? What was that like for you as a girl?

Parvin: At that moment, I saw myself simply as a human being in a class. But I could feel that many of the boys in the class were uncomfortable with my presence, and that, in turn, made me feel uneasy and out of place too.

Royesh: Did the boys in the class show any specific reaction to you being the only girl—anything that felt gendered?

Parvin: As far as I remember, the only thing that happened was that I had to sit alone in a corner of the classroom. I always tried to sit in the front row—because when you go to places like this, you have a goal, and there’s often unnecessary distraction. I always tried to stay away from those distractions since they weren’t aligned with my goal. So I sat in the front row, even if it meant being isolated. That feeling of being different, of not being part of the whole, was there—but since my goal was to learn, I tried to ignore it or at least not let it bother me.

Royesh: Has there ever been a moment in your life when you wanted to give everything up—and then something shook you awake, and you told yourself, “No, Parvin, you have to continue”?

Parvin: Yes, when I first came to Italy. It was my first year. The education system here is very different from Iran’s. While they have some similarities, the approach is not the same. It was also my first time living independently. Alongside university, I had to find a place to live, handle student residence permits—which, as everyone knows, involves very exhausting bureaucracy in Italy. All of this builds up and creates a moment where you want to do everything and at the same time, want to do nothing. It’s a sense of emptiness—like, “Why? What’s the point?” I think this happens to a lot of migrants. What I did was simply take an afternoon off—do nothing, think nothing—because everything in my head was tangled. And with the Italian system, you have to be very self-reliant to pass exams and even know how to study for them. It was tough, but gradually I started to prioritize tasks—what I could do and what I should do. And once I began ticking things off my checklist or to-do list, I slowly regained my motivation.

Royesh: People who’ve been through difficult times often share a common experience—they carry a sort of “magic phrase” with them. A short sentence they repeat in their mind that gives them hope. What has your magic phrase been, Parvin?

Parvin: For me, it’s a short sentence from my father: “Be successful, my child!” In Afghanistan, the word bacha (child) is typically used for boys, but my father would use it for all of us—both his sons and daughters. Ever since we were children, every time we left the house—whether it was for language class, school, an exam, or even something small—if my father was home, he would always say, “Be successful, my child. Be strong, my child.” Even now, sometimes before I leave my room for an exam, I close my eyes and try to hear that phrase echo in my mind. That sentence has always been with me—from childhood to now—and I think it will stay with me forever.

Royesh: Who has been the most influential teacher in your life?

Parvin: I believe life itself has been my greatest teacher. Life tests you first, and only then does it teach you. The lessons you learn from life—you never forget them.

Royesh: Have you ever had a teacher who said or did something that really inspired you?

Parvin: In grade 9, we had a teacher who taught us social studies. One day, she asked us a question: “Do you memorize the things I teach just to pass exams, or do you actually apply them in your life?” That question really shook me. It was something I should’ve asked myself. Are the things I study—scientifically, socially, in all ways—actually reflected in my life? That moment became a turning point for me, helping me realize that academic knowledge isn’t just for the academic world—it has real-world impact too.

Royesh: Awareness has a practical side, and that’s what your teacher was referring to. Do you think there’s anything you learned in school that, later on, you realized was neither knowledge nor practical?

Parvin: That’s a hard question—because you don’t always know whether something you’re learning now will be useful in the future. I might say something didn’t help me at all, but one hour later, maybe it will. One example: in high school, we had core subjects related to our major, like science, math, and physics—and we also had general subjects. One of them was a class called Hoviat (Identity). I always wondered what the point of that class was. It had concepts more relevant to law or political science students. But it turns out that one of the concepts we learned—about the definition of culture—came in handy just last week in a workshop I attended in New York. So sometimes, we think we’ve learned something we’ll never use, but life has a way of proving us wrong—even if it takes 10 or 20 years.

Royesh: Do you remember any of your classmates from school who still hold a special place in your heart?

Parvin: Yes, definitely. I still keep in touch with friends from school. If they ever see this program or video, I want to send greetings to Maryam, Zahra, and Reyhaneh. But because I was friends with Zahra and Maryam from the very beginning, I’d like to share the story of Reyhaneh. Reyhaneh and I became classmates in grade 10, but we became friends in grade 11. She later told me that in grade 10, she didn’t like me at all—she said, “I didn’t want to talk to you or even be around you.” It was because, in her previous school, she had been one of the top students, but when we became classmates, competing with me was very hard for her. But in grade 11, we both started attending English classes and had a better grasp of the language than our other classmates. I suggested we practice English together during breaks, and through our conversations, especially about Iran and Afghanistan’s history, we became close friends.

Royesh: And what about Zahra?

Parvin: Zahra was a very calm girl, like Maryam. Personality-wise, they were very different from me. I was always energetic and liked to do several things at once, but Maryam and Zahra preferred to be calm. When we talked, they would tell me that I brought more energy and movement into their lives. On the other hand, their calmness and simply being around them made me want to slow down and feel more peace and stillness as well.

Royesh: School life is full of bitter and sweet memories. If you had to choose one bitter and one sweet memory, what would they be?

Parvin: My most bitter memory was not getting into the gifted school, and my sweetest memory was when I participated in the Olympiad. The Olympiad wasn’t easy either. I could have participated in both the 10th and 11th grades. In 10th grade, I couldn’t because of bureaucracy—and simply because I was Afghan. I spent the entire 10th grade going back and forth with the school principal and the education department, trying to convince them to at least let me apply. The application system was designed only for Iranian citizens and required documents that only Iranians had. It took time, but eventually, I convinced them to let me register. I applied and participated in 11th grade. It was a mix of joy and disappointment: joy because I passed the first round, but disappointment because they informed me very late. Due to some circumstances, I didn’t have access to my account directly, and although I was following up, I found out too late that I had advanced to the second round. When I asked why, they told me the entire education department was looking for me—but only checked elite schools like Sampad or other top schools. They never thought to check ordinary schools. They said, “We didn’t believe a student from an ordinary school could participate in the Olympiad, let alone pass the first stage.” That made me realize that sometimes you’re in an environment where no one expects anything from you—but your potential exceeds their expectations.

Royesh: You said your most bitter memory was not entering the gifted school. Why?

Parvin: Because I really tried hard and thought I had convinced them to act fairly. I told them, “Let me take the test. If I don’t pass, fine. But if I do, allow me to join the school.” But they didn’t even check my exam paper. That, to me, was extremely unfair.

Royesh: I read in your record that at one point, despite many challenges, you were recognized as a top student. How did your classmates react?

Parvin: Some of them clapped for me, while others didn’t speak to me for several days.

Royesh: Can you explain that a bit more?

Parvin: That’s always the case—some people like you, some don’t, and some are neutral. Those who didn’t like me were obviously not happy. But those who liked me or had a neutral relationship were genuinely happy—especially a few of my teachers. Some even gave me gifts.

Royesh: How did you feel when you heard, for the first time, that you had been selected for the Olympiad?

Parvin: The path was never as smooth for me as it was for others. There was always an extra struggle involved. So it felt like both happiness and a hard-earned achievement.

Royesh: What was the most important thing you learned from the Olympiad—something that still stays with you?

Parvin: Time management. The Olympiad is an additional commitment—you can’t neglect your school subjects. At the same time as the Olympiad exams, I had midterm exams and was also working on obtaining a language certificate. So I had to manage multiple important exams at once. I think I learned very well how to manage my time during that period.

Royesh: What was the first book you read that had a powerful impact on your thinking or worldview?

Parvin: The first book that had a deep effect on me was one I read when I was very young. Since I wasn’t attending 7th grade, my father would buy us lots of storybooks. One was a science book titled “Darkness is Not Scary.” Many children fear the dark, but this book explained it logically and even gave practical ways to manage that fear. It was the first time I saw science and logic used to address something like fear. I think books like that sparked my love for science and shaped my curiosity. It also changed the way I looked at life. The book explained how to test your fears and prove they’re not so scary.

Royesh: Right now, hundreds of thousands of girls in Afghanistan want to believe in life and take it seriously—but they don’t know where to find that inner spark. If you were to recommend one book to help Afghan girls take life seriously and turn hope into something attainable, what would it be?

Parvin: I really admire Dr. Shakardokht Jafari. Some people watching this might say, “Yes, Parvin and others have had hard lives”—but I believe Shakardokht’s hardships were even greater than mine, especially because she didn’t have a supportive family and had to fight alone at every stage. The second point is that we often look for external sources—we want books, tools, and answers from outside. But sometimes the book we need is ourselves. We should look at what we’ve done, what we’re capable of doing—even if small—and just do it. I don’t want to give clichéd advice like “be hopeful” or “everything will be okay” because I know those girls experience something only they understand. So instead: yes, read books by Shakardokht Jafari, but also look inward. Ask yourself: “What can I do?”—then do it. As the saying goes: “If you can’t fly, run. If you can’t run, walk. If you can’t walk, crawl. And if you have to crawl—then crawl.”

Royesh: If you had to name one or two people who’ve inspired you in life, who would they be?

Parvin: My parents—without hesitation. Yes, there are many amazing people like Shakardokht, Sima Samar, and others—but for me, the first and strongest answer will always be my father and mother. They worked so hard and stood by us through extremely difficult times.

Royesh: If you had the chance to talk to a successful woman from anywhere in the world, who would you choose and what would you ask?

Parvin: I think Angela Merkel. I find her life very interesting—especially because she wasn’t originally involved in politics, but once she entered, she advanced powerfully and served as Germany’s Chancellor for a long time, playing a major role in shaping its policies. I’d want to ask her what it feels like to carry that much power—because power always comes with responsibility. I’d ask her: How did you manage such responsibility, and how did it affect your personal life?

Royesh: Why did you choose Italy for your higher education? Was it your only option?

Parvin: When I decided to apply for university, I listed countries where I could realistically study, then evaluated which ones matched my situation best. It came down to Germany and Italy. But since I wanted to study for a bachelor’s degree, and Italy had more English-language programs at that level—plus more scholarships and easier visa procedures—I chose Italy. It was a realistic decision, not an emotional one.

Royesh: Italy, with its deep history, offers a rich cultural experience to someone coming from a different world. What part of Italian culture stood out to you most when you first encountered it?

Parvin: One thing I noticed—not just in Italian but perhaps in broader European culture—is that aging doesn’t mean people give up on learning or living. Sadly, in my own experience, among some older Afghans, once they reach a certain age, they stop learning, stop living actively, and just wait for death. It breaks your heart. But Italians aren’t like that. I once spoke to a 74-year-old Italian man who was learning English. When I asked why, he said: “In school, we learned French as the second language, but now English is the global language. I want to travel and visit places—including America—so I need to know English.” I’ve seen many 50- and 60-year-olds say, “It’s too late for me, I can’t learn how to use a smartphone,” and things like that. But this man didn’t even think about difficulty—he just learned.

Royesh: In the “Leaders of Tomorrow” circle, we envision a new model of leadership—a model that’s different from historical male-dominated leadership styles. As a young woman, do you believe that the way you understand leadership is different from how a man might understand it, or from the leadership models history has shown us?

Parvin: Yes, definitely. Even though we all live in the same world, the world that women live in is very different from the one men experience. The challenges we face are different. That alone is enough reason to say that women’s leadership is fundamentally different from men’s.

Royesh: If you had to name three qualities of a good leader from a woman’s perspective, what would they be?

Parvin: First, empathy—the ability to feel with others. I think women tend to be better at that. Second, vision—though not all men are the same, generally they aim for high-level, perfectionist goals and then achieve some percentage of them. Women, on the other hand, often have more realistic visions, and when they reach their goals, they’ve usually fulfilled the entire vision they originally set. It may look smaller, but it’s complete. Third, team building. I don’t think this is gender-specific, but I believe it’s an essential skill every leader must have.

Royesh: These qualities can definitely be shared and taught. Do you consider yourself a leader today—a good one?

Parvin: That’s a challenging question. I consider myself the leader of my own life. As for being a leader for others—I’d rather let my actions, work, and achievements speak for themselves.

Royesh: You mentioned three traits of a good leader: empathy, having a vision, and team-building. In the work you do, in your relationships with friends, do you see these three qualities in yourself?

Parvin: Empathy, team-building, and vision—among these, I think I possess empathy and team-building. But as for vision, I feel I still need more study. I need to better understand what leadership should be, in what context, and for what purpose. So in that area, I feel I need more knowledge and can’t claim to be more informed than others.

Royesh: What is the biggest dream of 40-year-old Parvin?

Parvin: There’s something I’ve always noticed: when we’re kids, many boys complain, saying “There’s no Boy’s Day,” while there’s a Girl’s Day—or they say there’s no Men’s Day, while there’s International Women’s Day (March 8). What people often miss is the history behind these days—women have been victims, they’ve endured heavy social, political, and historical pressures. These days are to remember that. I would love to live in a world where we don’t need to celebrate March 8 anymore. A day when girls are so safe and empowered that no one has to remind them of their rights.

Royesh: If you had no limitations and were in a position of power to do something big—what would that be?

Parvin: If, as you said, I had no restrictions—if I had the magic lamp—I would wish that the word peace becomes something that every single Afghan, and hopefully every person in the world, truly lives, not just something they sing about or write poems about.

Royesh: Right now, millions of girls in Afghanistan sit behind closed doors, longing for education. What message do you have for them, as someone speaking from a better environment?

Parvin: First, I want to send you all my heartfelt greetings. And second—I want to say, don’t accept “no” easily. Yes, we may be living through hard times right now. But don’t forget hope. Over the past hundred years, Afghanistan’s flag has changed dozens of times. We don’t know what’s coming. A better future might be closer than we think. So let’s prepare ourselves for it—as much as we can.

Royesh: If you could go back to when you were five years old, playing happily in a park, and a boy comes from behind and pushes you down—you stand up and see 24-year-old or 40-year-old Parvin in front of you. What would you say to five-year-old Parvin?

Parvin: I’d tell her: The world is full of things you don’t understand yet—but you will. Keep walking. Don’t stop. Don’t start seeing yourself as the victim others might want to label you as. Being a victim and becoming a victim are two different things. You might fall, you might fail—but whether you stay a victim is something that comes from within. I’d tellthat little girl: never let anyone—including yourself—label you as defeated.

Royesh: When you walk the streets of New York or Washington these days, do you ever feel that all the hardships you’ve endured were worth it?

Parvin: If you had asked me before whether I thought I’d see New York or America at age 23, I would have said no—it seemed impossible. So being here, even for a short visit after moving to Italy, feels surreal. Walking these streets, seeing a different world, seeing other cities—it changes your entire perspective on life. It reminds you that there’s always something you haven’t seen, and always more to learn.

Royesh: The life you’ve described is one that transformed hardship into success. What does success mean to you?

Parvin: I think success is deeply personal. For me, success means being happy with myself, being surrounded by people I care about, and having no regrets.

Royesh: What are three words that define Parvin’s life?

Parvin: Perseverance, never accepting no, and effort.

Royesh: What is a phrase you tell yourself to stay strong and energized for the future?

Parvin: Parvin, you’re Parvin. When my father was choosing my name, he picked it from a name book and consulted my mother. He chose “Parvin,” which is the name of a cluster of stars seen in the night sky—used for navigation in ancient times. People in deserts or at sea used it to find their way. That makes me feel that I, as a person, am like that star cluster. So yes, I can keep going.

Royesh: If you could title your life as a book, what would the title be?

Parvin: I’ve thought about this before, actually—though not for a book, but a film. And a friend helped me with the phrase. I’d call it Feminine Resistance. We always hear phrases like “manly promise” or “act like a man.” But I want to flip that and say: Feminine Resistance.

Royesh: What’s the most important life lesson you’ve learned that you’d want to share with girls everywhere?

Parvin: The biggest lesson life has taught me is self-confidence. Believe in yourself and your abilities. First, build your skills. Then, believe in them. There were so many times when people told me I couldn’t—but I kept going, and I did.

Royesh: One last question. You have two audiences: one is the girls of Afghanistan, and the other is your parents. What message do you have for each?

Parvin: To the girls of Afghanistan—I want to say: being an Afghan girl is hard. Maybe you’re even tougher than stone. Respect.

To my parents—and I might get emotional here—dear father, dear mother, thank you so much for raising me to become who I am today.

Royesh: Thank you, dear Parvin.

Parvin: You’re welcome. Thank you.

Royesh: I hope that in the sky—a sky full of dreams—you, Parvin, continue to shine and gather all the stars around you.

Parvin: Thank you too.