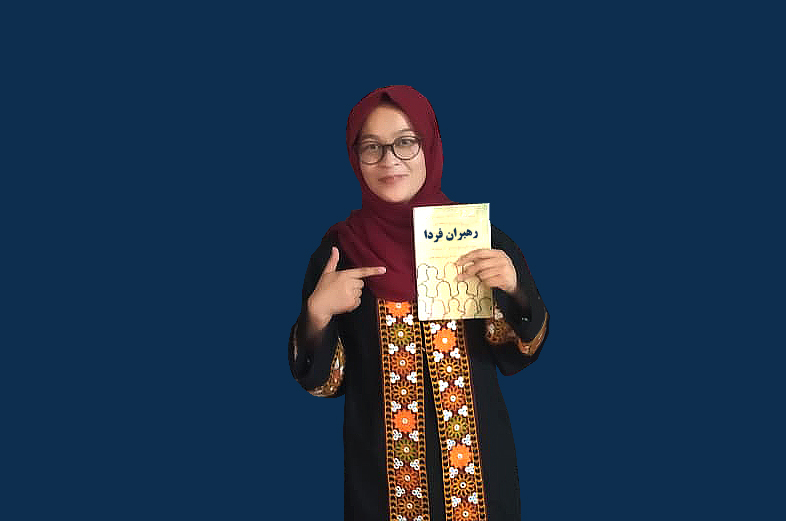

FutureSheLeaders (4)

Aziz Royesh: Sahar Jan, my dearest daughter—welcome from the bottom of my heart to the FutureSheLeaders series! It’s such a joy to have you with us.

Sahar Nikzad: Hello, teacher. Thank you so much. I warmly greet you as well. It truly makes me happy to see you again and to be part of the FutureSheLeaders series. I’m honored and delighted to be here with you today.

Aziz Royesh: It’s been three and a half—almost four—years since our paths first crossed on this long and meaningful journey. When you look back, Sahar Jan, what rises in your heart? While many spent these years caught in the shadows of criticism, despair, and complaint, how did you—Sahar, whose name itself means “dawn”—live through them?

Did you feel the warmth of your name, glowing like morning light on the horizon? Or were you still a hidden dawn—nestled in the heart of a long, silent night, waiting for the world to awaken?

If I’m being honest about how I feel, I can say this with a full heart: despite the school closures and all the restrictions over these past four years, when I look back and compare the girl I was then—the Sahar of four years ago—with who I am today, I see a world of change within myself. And much of that change has been positive.

Yes, schools were closed, and yes, we were denied so many things. But if I think about it differently—realistically—I can say something that might seem surprising: if those schools had remained open, I may never have met you. I may never have entered the Empowerment program or connected with the amazing people I’ve come to know through it.

Through Empowerment, I didn’t just study the five subjects in Cluster Education. I studied life. I learned how to find meaning, how to stand tall in silence, and how to search for light when the world turns dark.

That, to me, is a beautiful realization—because while others saw only loss and darkness, I discovered that real change can begin within the very limits we fear. I learned that even in the most confined spaces, we can grow. Even in silence, we can find a voice.

My name is Sahar. It used to be just a name to me. I never thought about what it meant or felt anything special in hearing it. But after sitting with you, after our talks and the time we’ve shared, I began to understand.

Sahar is the moment the night begins to fade. It’s the light that first dares to appear when everything is still dark—the fragile, beautiful promise of a new beginning. And now, I feel it deep inside me. Like my name, I, too, am a dawn. And yes, I now believe—I, too, am beautiful.

Aziz Royesh: Sahar Jan, how old are you now?

Sahar Nikzad: I’m 17 years old.

Aziz Royesh: So that means, when the Cluster Education and Empowerment sessions first began—about three and a half, maybe four years ago—you were around fourteen, or just turning fourteen and a half?

Sahar Nikzad: Yes, exactly. That’s right.

Aziz Royesh: Take me back to those early days, Sahar Jan. It was the beginning of a dark new chapter for Afghanistan. As a young girl just stepping into the world, how did you experience that moment?

What did it feel like to wake up one day and suddenly hear that girls could no longer go to school—couldn’t speak freely, laugh openly, or dream aloud? How did you, at that tender age, make sense of it all?

Sahar Nikzad: It was such a strange feeling—part sadness, part shock. I still remember those days clearly. People were whispering that the Taliban were approaching Kabul. My brother told me they had already taken Mazar and were advancing toward the capital. I remember saying, “No… that’s not possible!” I couldn’t believe it. It just didn’t seem real.

But the moment I heard they had actually entered Kabul—it was terrifying. I think it was during Muharram. We were at a gathering, and suddenly my mother came rushing in. Her face was full of panic. She said, “Sahar, we have to go—right now.” People around us were scattering; no one knew exactly what was going on.

We left immediately. I remember walking beside my mother, noticing how anxious she was. I asked what had happened, and she said, “The Taliban are here. They’ve taken over. The police have disappeared. There’s no one left to keep order. It’s not safe—let’s just go home.”

Even then, I couldn’t fully accept it. But over the next few days, the reality started to sink in. Then came the official order: schools were closed, and girls were no longer allowed to attend.

For me, that was heartbreaking. My life revolved around school. Every day was full of learning, laughter, and song with my classmates. And suddenly—all of it was gone.

I would lie awake at night, restless. Sometimes I’d even talk in my sleep. In the mornings, my mother would tell me, “You were talking again… saying the Taliban came, and the schools were closed.” That’s how deep the fear had entered my mind.

Around that time, one of my closest friends left for Germany. Our family, instead, decided to go to Mazar. Though it had also fallen to the Taliban, things felt a little calmer there. So we left Kabul. But inside me, I carried this sinking feeling that everything I’d hoped for—everything I’d dreamed of—was slipping away.

I started thinking maybe my life would take a completely different turn. Maybe I’d never study again. Maybe I’d learn tailoring or beauty work, like many other girls—something to help me survive. I was preparing myself for that. I was beginning to let go of the dreams I had worked so hard for.

But then, one day, I received a call from the principal of our school. She said, “Come. Cluster Education has started. It’s a beautiful program, and we’d love for you to be part of it.”

When I heard that, it felt like light breaking through a very dark sky. I was genuinely overjoyed. It meant I could still study. We had found a way. We hadn’t been forgotten.

Aziz Royesh: During that time, so many girls across Afghanistan were brought to tears. Tell me, Sahar Jan—were you one of them? Did you cry too?

Sahar Nikzad: Yes, I did. When I first heard the news, I cried. The closure of schools wasn’t just news to us—it was a heartbreak, a deep wound. For girls like me, whose entire world revolved around learning, it felt as if a door to our future had been slammed shut. It truly hurt.

Aziz Royesh: We saw so many heartbreaking images—girls standing outside the gates of their schools, weeping… crying in the streets, clinging to one another in sorrow. They wept not just for their schools, but for their stolen dreams.

Did you ever have a moment like that, Sahar Jan? Did you cry in the presence of your classmates—among your schoolmates, in shared grief?

Sahar Nikzad: No, as far as I remember, I didn’t cry in front of my classmates. We left for Mazar almost immediately after the news broke, so we didn’t even get the chance to sit together and share that moment of sorrow. It all happened so fast—there was no time for that kind of goodbye.

Aziz Royesh: And now, when you look back on those days—on everything that was left unsaid and unfelt—do you ever feel like you still owe yourself a deep, unspoken cry?

Sahar Nikzad: No, I don’t think so.

Aziz Royesh: Alright, Sahar Jan—let’s talk a bit about your studies. When everything suddenly changed, what grade were you in? And which school were you attending at the time?

Sahar Nikzad: At that time, I was in 9th grade. We had finished about half of the academic year and were right in the middle of our mid-term exams when everything came to a halt. I was studying at Bamika Elite High School—the very place where, later on, the Cluster Education program was launched.

Thanks to that program, we were able to quietly and courageously continue our education. And through it, I was able to complete 10th grade as well.

Aziz Royesh: In the Cluster Education program, you engaged in a series of activities—exercises designed to help you and your peers cope with the painful reality that Afghan girls are living through today, and to resist the weight of despair.

Tell me, Sahar Jan, what was the most important thing you took from that experience? Was there an idea, a moment, or a spark that gave you hope? What helped you return to yourself—to rediscover who you are and to stand strong beside your friends, even when everything felt uncertain?

Sahar Nikzad: The first and most powerful thing that’s kept me hopeful to this day is my dream—my own personal dream.

Before joining Empowerment, I didn’t really have a clear sense of what my dream was. I hadn’t defined it. But through the Empowerment sessions, I came to understand what it truly means to have a dream—to carry something inside you that gives meaning to your struggle.

That realization changed everything. It gave me motivation. It gave me persistence. And, most importantly, it gave me discipline—the strength to keep going when everything else seemed to be falling apart.

When I was with my friends, what kept us connected wasn’t just the classes or the setting—it was our dreams. Each of us carried a dream, both personal and shared. And that sense of purpose was what helped us hold on to hope and to one another.

Aziz Royesh: In the Empowerment sessions, was there a particular exercise or idea that first sparked your excitement—something that made you say, “Yes, this is meaningful; I want to keep going”? What was that turning point for you?

Sahar Nikzad: From the very first day Empowerment began, I remember it clearly—I was the first student to have an interview with you. We sat together and talked. At that time, many of the terms we discussed felt unfamiliar. They sounded simple—words like “self,” “name,” “identity,” and “the other.” But to be honest, I didn’t really understand what they meant. I only knew them from literature class, where “self” was just a pronoun or a grammar point—nothing more.

But as the sessions continued, something began to shift. I started to see things differently. I came to understand deeper concepts—like the power of the self, the idea of limiting beliefs, and how we can transform those beliefs into supporting ones. That was a turning point for me.

Gradually, I began to realize these weren’t just words—they were tools for life. They had the power to help us shape a beautiful future. For me, Empowerment became exactly that: the art of creating a beautiful life.

The exercises were incredibly meaningful. I remember the one where we were asked to look into our own eyes in the mirror—to really see ourselves. That moment made me think deeply about who I am. We explored how our “name” and “identity” come from the outside, but they don’t always reflect our true self. It was fascinating.

And then there was our conversation—you helped me understand the meaning behind my name. That moment stayed with me. It gave me a new connection to who I am.

There were so many moments like that—beautiful, thought-provoking, eye-opening. And among all of them, the idea of having a dream stood out the most. I still remember that line: “Every human has a dream, and anyone without a dream is not truly a human.” That sentence struck something deep within me. And now, I truly understand just how essential it is—for every person—to carry a dream in their heart.

Aziz Royesh: Specifically, which exercise brought you closer to your friends? Was there a particular practice in the Empowerment sessions where you felt your bond with them growing stronger each day —where the sense of connection and friendship deepened through the process?

Sahar Nikzad: The “Peace on Earth” game was one of the best activities for me. We had seven actions to complete, and the first step was to form a group. That’s how we created our team —a close-knit group of five girls from different places. We gradually became friends and had to find our common ground. What united us was our shared dream: we all wanted to bring peace to our society and to Afghanistan. Little by little, the friendship-building exercises brought us even closer —we started visiting each other’s homes and working on different activities together. For example, we went to events like the International Day of the Girl, where we shared our stories, talked about our dreams, and set goals for ourselves.

Aziz Royesh: One of the most powerful impacts of the Empowerment exercises is that they introduce you to very simple, natural activities —things you already do in your everyday life, but perhaps don’t notice their deeper importance. Many of your peers, in the groups you were part of, carried out beautiful symbolic actions. Could you share some examples of these? What kinds of activities did your groups take part in?

Sahar Nikzad: We did many symbolic exercises, and one of the first was celebrating the International Day of the Girl. On our first day at the cluster center, all the students were still inside their classrooms. We went into the courtyard during break time, and slowly the girls began coming out. We sang songs for them and spoke about girls —their value, their strength. It created a wave of positive energy and helped them recognize their worth. Some of them had even forgotten that it was the Day of the Girl. This symbolic act was really special for us.

At the end, we all raised our hands and gave ourselves words of encouragement —saying things like “I can,” “I am a girl,” “I love myself.” When you stand in a group and everyone is raising their voice together, it feels truly powerful and beautiful. Another beautiful activity we did was the candle-lighting ceremony. One day, we went out and used leaves to create the symbol of peace —the circular shape with lines through it. Then we handed out candles to others. But it wasn’t that each person lit their candle on their own; instead, we would light one candle and pass it to someone else so they could light theirs from ours. It was such a meaningful moment. It showed that when you have strength or knowledge, you can share your light with others without losing any of your own. Afterward, we placed all the candles together to form the peace symbol. It turned out beautifully and felt deeply symbolic.

When we went to Marefat School, our goal was to ask others about their dreams. Before that, I had been there once as the host of a mathematics olympiad, and during that event, I shared a meaningful story and repeated a sentence: “I am because we are,” or “We are because I am.” Everyone—thousands behind me—repeated it together. That gave me such a powerful feeling. My goal was to create a sense of peace and unity among people. Later, at the end of the event, we asked people to write down their dreams on cards we had prepared. We gave a card to everyone. Some wrote just a single word, others shared their wishes —many wrote about the hope for a better Afghanistan, or dreams like becoming an astronaut. That day, I realized something: everyone has something they long for. Whether old or young, everyone carries a dream in their heart.

Aziz Royesh: Some of the symbolic actions carried out by your groups were truly beautiful. The teams often worked together on initiatives that brought them closer to one another and also reached out into the wider community —without requiring much expense or causing any trouble. Do you remember any of these activities? Were there any creative or meaningful initiatives that stood out to you as especially inspiring or innovative?

Sahar Nikzad: For Mother’s Day, four of our groups came together —four teams of five girls, about twenty of us in total. We gathered in the school courtyard. It was a Friday. Each of us could bring our own mother and one more guest, and we each brought a simple lunch dish —like cauliflower stew, rice, or macaroni—enough for two people. That way, we didn’t need anything extravagant; just the food we would normally eat at home. Altogether, we became around 40 to 50 people. We came with our mothers to celebrate Mother’s Day. My grandmother had just come from Mazar, and she joined us too. We all sat around one large table and shared our food. Each person brought something, and together we created this big, beautiful, shared table filled with traditional Afghan dishes like cauliflower curry, ashak, and other homemade foods. It was one of the sweetest experiences of my life—for me, for my mother, and for my grandmother. My grandmother was so touched that afterward she called people —she even called my uncle—to tell them, “My granddaughter celebrated Mother’s Day for me today, and it was in such a warm, heartfelt gathering with her friends.” This was one of the symbolic acts where we not only connected with one another, but also with each other’s mothers. I truly love that memory—it’s a day I’ll never forget.

Aziz Royesh: Were there any other initiatives—either ones you took part in or heard about from your peers—that you found especially interesting or inspiring? Something a classmate or teammate did that really stood out to you as a creative or meaningful idea?

Sahar Nikzad: We had many different groups, and each of them carried out a variety of creative exercises. For example, members of one group pricked their fingers and touched the blood to each other’s mouths —as a symbolic gesture based on an old tradition. It created a deep emotional connection between them, as if they were becoming blood sisters. I found that very moving and unique. In another case, one of our friends took a single piece of bread, sat with others, and divided it into several pieces —sharing it with five or six girls. That simple act of sharing a single piece of bread was so powerful that by that very evening, the story had reached six other families. People were saying, “Five girls came and shared their bread with us.” On the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, some of our friends used colored powder and pressed their painted hands onto posters, creating messages of solidarity. Others made handmade bracelets and gave them as gifts, saying, “This is a small present for you.” We also created small, personalized cards and used them to celebrate different occasions for others. These small tokens were taken home, and the smiles we saw in return meant so much to us.

Another group made bead bracelets and gave them to different people. One of the girls even gave a bracelet to a local mullah and told him, “Take this to your wife and wish her a happy Women’s Day.” The story she shared with us afterward was truly touching. She said the mullah laughed warmly and told her, “This is the first time I’m giving my wife a gift and wishing her a happy Women’s Day.” These were some of the beautiful and symbolic experiences we shared—simple yet powerful moments that stayed with us.

Aziz Royesh: In addition to the exercises and activities you carried out within your groups, you also took on a very meaningful and impactful role in promoting literacy and raising awareness within the broader community. What kind of initiatives did you undertake in that area? How did the idea emerge—that you, as students, could become literacy teachers yourselves, and take the knowledge from your school into your families and communities? How did you put this into practice, and what kinds of challenges did you face along the way?

Sahar Nikzad: We had a five-member group called “Peace.” Later, we decided to expand our activities—since we had the time and opportunity —to different mosques in our area so that our efforts could be more impactful. There was one sentence that always stayed in the minds of me and my friends: “Every real change in a family begins at its root, at the heart of the family —and that heart is the mother.” That sentence always felt meaningful to me —and I truly experienced its truth. We thought, how beautiful it would be to begin change from the very heart of the family: the mothers. We realized that if we wanted to create real change in society, it had to begin with awareness and literacy. So, we made the decision to start promoting literacy inside the homes, right at the heart of the family. We joined with another five-member group and went to speak with the leaders of a local mosque. At first, we met with a representative of the mosque which was full of experience. For him, it was surprising—and even moving—to see a group of 15- or 16-year-old girls approaching someone older, talking about their desire to create change. Especially knowing that we had no external support, no salary, and no formal backing. He asked us how we were willing to dedicate our time like that. We began teaching literacy classes at a mosque near our school. At first, we thought there might be obstacles or restrictions, but having a dream—and especially the dream of peace and awareness —gave us the motivation to continue. It gave us the strength to bring change into the lives of mothers.

Aziz Royesh: In this Hamdeli (Compassion) Association program, how many students did you have in total? How many classes were formed? And how many of your classmates were directly involved in running or supporting this initiative?

Sahar Nikzad: There were about 12 of us involved, each taking on different roles—some as teachers, others as coordinators or organizers. In the first days after we announced the program, around 80 women came and registered. We organized two time slots. We deliberately chose times that wouldn’t interfere with the women’s cooking or household responsibilities, and also not too early in the morning. So we picked midday sessions. We had two shifts. We started with that group of 70 to 80 learners. The very first student who joined us was my own mother. She said, “I’ll go today and be the first to register, because my daughter has stepped up and wants to bring change —she wants to teach. So I’ll be my daughter’s student.” Along with her, some of my friends’ mothers—who were also part of the teaching team—joined as well. A few more women came too. It had a deep impact on all of them, especially on my own mother. We have so many sweet memories. For example, I would walk home with my mother after class and help her with her lessons. In the beginning, she was really scared to go up to the board—she would get nervous. I told her, “Why are you afraid? There’s nothing to fear. Never be afraid of failing—you just have to keep moving forward.” After a while, whenever the teacher asked who wanted to come to the board, my mother was the first to raise her hand and say, “I’ll go!” She would walk up and write with confidence. These changes might not have been obvious to her, but to me, they were crystal clear. Later, she would say, “Studying is so enjoyable—it brings such joy. I’ve never found this kind of joy in anything else.” Truly, the work we were doing was meaningful. It made a real impact.

Aziz Royesh: Had your mother never studied before? Had she never attended school at all?

Sahar Nikzad: My mother had only studied the Holy Quran —what we call the “Haft-Yak” book— but nothing beyond that. She didn’t know how to read or write.

Aziz Royesh: One of your students—the one whose photo and video you had shared— was around seventy or in her early seventies, and she had high blood pressure. She said that ever since she joined your class, her blood pressure has come under control. What’s her story?

Sahar Nikzad: There was a 70-year-old woman—truly elderly. Just by looking at her hands, you could tell how frail she was. But still, she would always come and take part in our literacy classes. One day, we wanted to understand what impact the lessons were having on her, so we asked her. She said, “I used to have high blood pressure, but ever since I started coming here and joined your classes, I feel much better.” Because of her age, she no longer had many responsibilities at home —perhaps she mostly spent time with her grandchildren, She said, “When I joined this program, I got to meet new people —I connected with other women, with the teacher, and with new friends.

We would spend a few minutes chatting, and then a few more learning something new. All of that gave me such a good feeling.” And it was that sense of emotional well-being and inner peace that may have helped regulate her blood pressure —it might have truly made a difference in her health.

Aziz Royesh: Over the course of two, three, or even five months of teaching, how much did your students progress in their reading and writing skills? And how much did their understanding—especially in relation to the discussions you had with them—improve during that time?

Sahar Nikzad: In the early days of the literacy classes, it was truly difficult for the older women. It’s very different when a first grader is seven years old, compared to someone much older who is just beginning to learn.

For many of them, even holding a pen was a challenge. Our teachers—and even I myself—would often go and gently hold their hands to help them write properly, guiding them through the motion so they could form letters and sentences. But over time, the progress was remarkable. Within just four to five months, many of them had developed beautiful handwriting —some even wrote more neatly and clearly than we did! Some of them were writing even more beautifully and neatly than we did—and this transformation happened within just four to five months.

Some of them would say, “Now we truly understand the value of education.” Some of them had previously placed restrictions on their daughters —preventing them from going to school or attending courses due to security concerns or other reasons. They genuinely entrusted their daughters to us… Some even asked, “Do you have any programs where our girls can come and study?” These were powerful and varied experiences. In the beginning, some of the women couldn’t even speak in front of a blackboard. But later, they began appearing in videos and speaking beautifully at different events and on various occasions.

Aziz Royesh: You faced two major challenges as a young teacher: first, getting older women to take the lessons seriously, and second, getting them to take you seriously. What did you do to ensure that these women not only valued the learning process but also respected you as their teacher? How did you help them approach both you and the lessons with seriousness, while also keeping things warm, joyful, and pressure-free— so that learning didn’t feel like a burden or obligation, but something they could enjoy and feel at ease with? What was your secret? What was your special skill in this part?

Sahar Nikzad: At first, when the women would come to class, there was a lot of noise and distraction. Some even brought their small children with them into the classroom, which naturally disrupted the lessons. At the beginning, they didn’t take us very seriously. But gradually, they began to see for themselves that bringing children or not paying attention was affecting the class. Little by little, they realized that they shouldn’t bring the kids and that they needed to take the lessons seriously. Also, missing just one day of class—whether due to a funeral, a wedding, illness, or something else—had a noticeable impact. Some of them would return after a few days and realize they had fallen behind. That made them feel pressure and even disappointment in themselves. Over time, they came to understand how important consistency and regular attendance really are. For example, whether they missed a day for various reasons —or simply didn’t feel like coming— they later came to take it seriously and attend the classes regularly. They did not take the classes seriously because of the teachers’ attitude, but rather because of the beautiful feeling and joy they found in learning, which motivated them to continue their studies. Gradually, they came to truly understand the value of reading and writing. Later, when they could look at a blackboard or a sign and recognize a letter—an ‘A’ or a ‘B’ —they began to feel the joy of learning. That joy grew stronger with each day, and compared to the early days, you could really see a change in them.

Aziz Royesh: In your group, there were some students who seemed in a rush, a bit restless —often filled with excitement about the concepts they were learning in the Empowerment sessions. They couldn’t wait to share those ideas with others —whether with their families or classmates. Did it ever happen that one of the girls shared these messages —like “You are a woman, you are free, you have the right to choose, your desires matter, don’t stay silent under pressure, don’t bow to hardship”—with other women or girls? And did those words ever create challenges or problems for you or your classmates?

Sahar Nikzad: Yes, I have a very interesting story to share. My mother and the mother of my friend, Mursal, were very close, so sometimes they would talk about things we had discussed in class. Our group leader, Suraya, once shared a personal story in class and encouraged us by saying, “Women should always be independent and free. Don’t rely on your husband for money —you should stand on your own feet.” Later, one of the women who heard this message through her daughter said, “But I have no income; it’s my husband’s responsibility to provide me with money. How can I be independent or free if I don’t have a job? Being a mother is already my duty.” They took it very badly—wondering how anyone could say things like “you are free” and similar ideas. This experience taught me that we can’t impose or explain these concepts all at once. People face different limitations, and it takes time to help them understand what freedom truly means. Freedom has many forms, but we can’t expect someone who holds deeply rooted beliefs from the past to suddenly change and accept a new way of thinking.

Aziz Royesh: One of the most difficult challenges for you and your generation during the Empowerment sessions was confronting two deeply rooted issues in your society: violence and hatred. Violence had long been institutionalized, manifesting through war and destructive conflicts among different groups, ethnicities, and communities. Hatred, too, was visible—in people’s expressions, their words, and their judgments about almost everything. But you chose a completely different path: one that called for stepping away from both violence and hatred. I’d like to ask—how did you confront these two destructive forces? What was your personal experience in dealing with violence and hatred? How difficult was this journey for you? Or was it, in some ways, easier than expected?

Sahar Nikzad: Violence and hatred are widespread in Afghanistan— violence from women toward men, men toward women, and in many other forms. We also experience violence in response to the Taliban, who themselves express deep hatred toward women. All of this holds our society back. But these very limitations, this violence and hatred, are what we must gradually learn from and work to overcome, step by step, if we want to move forward. Many people say they hate the Taliban and that we must fight them. But in my view, if we don’t stop the cycle of violence now

—and if we ourselves carry hatred toward them— it will only cause more harm to us, first and foremost. Every time we insult them, or even direct our anger toward someone else, like men in general, I believe we are also inflicting psychological harm on ourselves.

Aziz Royesh: Sahar jan, during this period, women and girls have faced incredibly difficult circumstances. The Taliban adopted an approach that —whichever way you looked at it— was rooted in violence, hatred, the suppression and humiliation of women. As a result, many women began to respond with harshness of their own— seeing the Taliban as enemies to be eliminated, feeling justified in hating them, in cursing them. I want to ask: During your studies and empowerment programs, did you ever personally encounter a Taliban member? Were you or your teachers ever harassed or harmed by them? Did you ever feel your education was in danger of being stopped or silenced because of their actions?

Sahar Nikzad: From the very beginning of the Taliban’s return, a sense of violence and hatred took hold of almost every Afghan. But one of the most important lessons I learned in the Empowerment sessions was this: “Change your perspective.” That idea truly stayed with me. I began to shift how I viewed the Taliban and the government. Yes, these restrictions exist across Afghanistan and deeply affect girls —but even within those limits, we found ways to continue learning. Maybe our path was different, maybe more difficult, but we never abandoned our purpose. It’s like walking through a street filled with trash or stonesn—we accepted it as part of reality. We stepped over the dirt and stones and kept moving forward.

In the same way, when we walk through streets where there are many boys and men, our mothers tell us, “Be careful, keep your head down”—and we follow that advice. Some people say, “That man looked at you in a certain way, with a gendered or inappropriate gaze.”

But I don’t always see it that way. I say, maybe his look wasn’t meant to offend—maybe it was a kind look, maybe even a sign of affection or care. The Taliban and the current situation are similar in that sense. Despite all the challenges, we’ve been able to accomplish things now that we hadn’t done even during the Republic —like literacy programs, community groups, and other initiatives. Through these efforts, we’ve been able to bring light and hope into the hearts of hundreds of families.

Aziz Royesh: Over these past three or four years, has there ever been a moment when you felt completely stuck? A time when you lost hope, felt defeated, and thought to yourself, “This is the end—I can’t go on any longer”? Has that ever happened to you?

Sahar Nikzad: I think it’s completely natural—every girl living in Afghanistan right now has likely experienced this feeling. For me, it especially happened when the Taliban returned and, after a few years, shut down the educational courses again. In those moments, I truly felt like the world had ended. I thought, “If I keep going, maybe it won’t make any difference anymore.” It felt like I had hit a dead end, with no way forward. But then, after I cried, after sitting quietly with myself for a while—sometimes just a few minutes, sometimes longer— a vision would rise in my mind, a voice in my imagination saying: “Sahar, because of the dreams you carry, this is not the end. Many girls may be fleeing to other countries, escaping even worse situations—but you, you must keep going.”

My dreams were always with me. I constantly tried to keep them alive. Just imagining my dreams over and over helped me hold on to hope and carve a path toward survival and purpose.

Aziz Royesh: Earlier, you mentioned one of the Empowerment exercises —looking into a mirror, gazing into your own eyes, and speaking to yourself through them. Do you have a personal experience with this exercise that you’d be willing to share with us?

Sahar Nikzad: Yes. At first, this exercise seems strange and even a bit simple. But when I actually tried it, it was incredibly powerful. I had a small mirror, and I sat down in front of it. I started by looking at my face —first noticing my features, my eyelashes— and then slowly moved deeper into the experience: looking into my own eyes. At first, it was a little scary—because you’re suddenly face-to-face with yourself, really seeing who you are. It’s a strange feeling, like asking: “Am I really Sahar, or someone else?” You begin to remember: This is Sahar—the one who lived through those moments, who experienced all those things. After the games and activities we did —and as I held on to my dream—visions would come before my eyes. One by one, the lessons life had taught me would resurface. And as I looked at them, I realized that each one was part of life itself, part of its beauty—each filled with meaning, and each a piece of something truly beautiful.

The sorrows, the sadness, and the hardships we faced—whether in the past or still happening now—they were there too. But standing across from them were our dreams, our goals, and the changes we had made. The last time I did this mirror exercise seriously —actually the second time I tried it— I had reached a point where I truly felt, “No, I can’t go on anymore.” Those thoughts were heavy, and they kept coming back. So I sat in front of the mirror and asked myself, “Who are you, really?” It felt like a moment to cry out, to confront everything. Slowly, I started telling myself: “Yes, I am Sahar— and that name carries meaning. It means the one who must shine even in the darkest moments.” I reminded myself that I have to keep reading, keep studying, keep moving forward. That whole experience was the most beautiful one of my life.

Aziz Royesh: As an Empowerment activist, as a girl with dreams for the future, and as someone who aspires to be part of the next generation of leaders—leaders who embody a new kind of leadership in the world you hope to live in— when you look at the Taliban, how much do you think they are capable of change? Despite the power the Taliban currently hold and the restrictions they have imposed, Is there any room for change in their mindset, in their behavior, or in the way they interact with society? Do you believe that you—through your vision, determination, and leadership—can still change Afghanistan, and even the world beyond?

Sahar Nikzad: I believe we, as women and girls, have a unique power —the power to redefine the Taliban and their government from a different angle. Just as we redefined the local mullahs in our communities —so much so that they opened the doors of mosques to us, allowing us to teach women —we have also, over the past three or four years, managed to reshape the presence of the Taliban in ways that served our own goals and needs.

I remember one particular incident. One day, a Taliban member came to the mosque for security inspection and asked, “What are you teaching here? What kind of education is being provided?” He told the mosque caretaker, “Go and call the person responsible for this program. Why are schools closed, yet here they are teaching literacy to mothers and other women?” At the time, I was the program coordinator, so I went to meet him. I was afraid at first, but I decided to speak with him and see what he had to say. We talked, and to my surprise, he treated me with respect. He asked what we were teaching there. I told him, “We’re teaching the Qur’an and basic literacy to women. We have this opportunity, so we’re making the most of it.”

Instead of getting angry, he was actually pleased. He said, “Well done for coming here to teach the Qur’an and literacy, so that women can understand themselves and learn about their religious duties.” His response was unexpectedly positive. He even gave us a few warnings, advising us to be cautious about who enters the mosque. Then, quite remarkably, he told me personally, “If anyone ever bothers you—even if it’s midnight—get my number from the mosque caretaker and call me. I’ll come right away.” His words gave me a sense of support —a feeling that not only had they not closed the doors of the mosque to us, but stood behind us. He even said, “If anything happens, call me—I’ll come.”

To me, that moment reflected the true power we, as women, hold—the power to give meaning even to the presence of the Taliban. What I’m saying doesn’t mean that I support the Taliban or that I admire them —but I do want to emphasize how important our perspective is. I choose to look at the situation from a different angle. Yes, the Taliban have done many harmful things. But alongside all their wrongdoings, some small openings have also been created. For example, my friends and I have been able to bring about gradual changes. First, we shifted our own perspective —and that allowed us to move forward on a different path.

Aziz Royesh: That’s a fascinating experience, Sahar jan. The shift in perspective that you mentioned is exactly what we focus on in Empowerment. When you’re faced with a challenge or a difficult reality, the idea is not to wrestle with the problem itself —because as we say, “a problem only produces more problems.” It’s like having a blemish on your face: the more you press on it, the worse it becomes. The key is to change your perspective—to turn around and look at the situation from another angle. That Turn Around gives you vision. You begin to see that the issue isn’t just one problem—it’s part of a bigger context, with many layers and many possible solutions.

And that’s exactly what you’ve practiced. You learned to walk through a street and not see the stones as mere obstacles, but as steps you can use to move forward. You stopped seeing people in that street as threats, assuming their gazes were harmful. Instead, you dared to believe their looks might hold appreciation, kindness, or even admiration for your strength and beauty. Similarly, you’ve chosen not to see the Taliban only as those who close school doors or treat women harshly, but to also notice the rare moments when they’ve offered space, protection, or understanding—even if small. That is the power of perspective, and it’s a key learning in Empowerment.

Now I wonder—have you heard similar stories from your friends? Or in the course of your Empowerment sessions, have you witnessed anyone —either yourself or someone close to you—who used these practices to create a real, meaningful shift in their life? A moment that was deeply inspiring or transformational?

Sahar Nikzad: There are so many experiences—both my own and those of my friends. But one that truly inspired me was the story of a girl whose parents had lived apart for nearly fifteen years. They held deep resentment and anger toward each other. This girl, however, had attended the Empowerment sessions—she had even spoken with you, I believe—and took detailed notes from everything she learned. Eventually, she made a powerful decision: she said, “Let me change my own perspective first, and then try to shift my parents’ perspectives too—so they might reconcile and find peace.” With that mindset, she approached both her mother and father, and told them: “I am not the product of your violence and hatred—I am the product of your love. Once, you truly loved each other, and I am the beautiful result of that love.”

She began to remind them of their sweet memories, of the moments they once cherished. Slowly, step by step, she helped them see each other differently. And after about five months, she succeeded —not in getting them to remarry, but in helping them rebuild a sense of mutual respect, kindness, and warmth.

Their hatred faded, and love—perhaps not romantic, but human and healing—returned between them.

Aziz Royesh: That was truly a powerful and successful practice. She was able to transform deep-seated resentment and hatred into reconciliation and mutual respect—simply by reminding her parents of her role as the shared result of their once genuine love. And now, it’s been about eight months since that moment.

Sahar jan, one of the most remarkable recent developments among the Hazara community was the celebration of Hazara Cultural Day. It revealed a burst of energy—an expression of joy, music, art, sports, and creative spirit that had long been held back.

When you look at this event through your own unique lens, do you feel that part of your hopes and dreams began to open up more fully on that day? Do you feel that the dreams you’ve been working so hard to realize are, in some way, actually beginning to take shape? Do you sense that Hazara girls—your peers—are slowly changing their perspectives too? That they’re beginning to reshape their tastes, their identities, and their aspirations? And that perhaps, little by little, our society is transforming—from one that was often sad, harsh, and joyless, into a community that is vibrant, hopeful, joyful, and full of beauty and new vision?

Sahar Nikzad: Yes, absolutely. When I hear about Hazara Cultural Day, and see the many videos and celebrations that are shared each year, it fills me with hope. Every time this day comes around, people send me messages of congratulations. What’s even more moving is seeing how, compared to the past—when women and girls weren’t even allowed to step outside or pursue education —they are now standing proudly in public spaces during these celebrations. We now see women and girls singing, wearing beautiful traditional clothes, dancing, reciting Hazara poetry, and performing songs with such grace and confidence. It’s a powerful transformation. Women are not only participating—they are sharing the stage with men, creating a unique sense of warmth and unity between the two. We’re also seeing beautiful Hazara dramas and films being made. I genuinely enjoy watching them. They show that Hazara women have begun to find their voice and place —speaking eloquently, appearing confidently in front of cameras, acting, and proudly showcasing their culture and language. It’s deeply inspiring.

Aziz Royesh: Sahar, what is your relationship with books and reading like? How often do you read? What kinds of books do you enjoy the most? And so far, which books have inspired you the most in your life?

Sahar Nikzad: I consider myself someone who truly loves reading. I’ve even created a personal schedule to keep up with the books I want to read. Most days, I read regularly—though of course, there are some days that pass without reading. I especially enjoy books that focus on personal growth and self-development —books like The Universe Has Your Back, The Magic Shop, and others that explore themes from psychology. I once heard a quote that said, “Books are the cure for every pain.” And honestly, that’s how I feel. When I pick up a book, it genuinely helps me. Often, I find myself relating deeply to the main character—especially when they’re going through something painful. Their journey gives me hope. If they could find a way through it, maybe I can too. Another category I love is biographies. Without having to live a thousand different lives, or be born a thousand times, books allow us to experience countless lives in just one lifetime.

One of my favorite books has been The Magic Shop. It really resonated with me. It’s about a boy who struggled from a young age, yet managed to change his life through meditation, visualization, and the power of his dreams. Despite many limitations and challenges, he ultimately achieved the life he envisioned.

Aziz Royesh: What kind of relationship do you have with painting and music?

Sahar Nikzad: I really love painting. It gives me the feeling that, with my own hands, I can draw a future—or a moment—that I dream of. I have a sketchbook where I not only write down my goals but also illustrate them. For example, I’ve drawn the body image I hope to have—my ideal height and weight. I’ve sketched places I want to go, like universities, cafés, and famous spots around the world. Drawing these dreams gives me a powerful sense that I am creating something real. It makes me feel like one day, those dreams will come true. That’s the magic painting for me. Alongside painting, I also deeply love music—especially the piano. I dream of one day playing it with my own hands. Unfortunately, in Afghanistan, it’s not really possible to own a piano or practice freely. But I do have an app on my phone that lets me play virtually. Even that brings a sense of peace. For a few moments, I can escape the noise of the world, stop thinking about everything else, and just be still.

Aziz Royesh: How much do you write each day? And how often do you spend time with your daily reflection journal?

Sahar Nikzad: Writing, for me, is a form of joy—almost like a personal retreat. I don’t write every single day, but I never abandon it either. I have a special notebook that serves both as a gratitude journal and a daily reflection diary. Almost every night, I date a new page and write down what happened that day—especially the things that made me feel happy or thankful. For example, I’ll write, “Thank God, this issue was resolved today,” or “We visited this place today.” These small reflections give me such a good feeling. And then, when I go back a few days later and reread them, I realize, “I was so worried about this—but it actually worked out.” Sometimes I write down the questions that trouble me during the day. And a few days later, I find that the answers have come to me, often without me even realizing. Alongside that, I write down personal memories—what I felt that day, whether I was happy or sad. Writing often gives me a deep sense of freedom and release. When life feels overwhelming, I turn to my notebook. I write as if I’m speaking to God—pouring my heart out on the page: “This is my letter; this is where I’ve arrived today.” I felt so much pressure then, but now it’s behind me. Some of my pieces have been published—about five or six in Shesha Media, and others in (8AM) and Rukhshana Media. Overall, writing gives me a beautiful feeling of liberation.

Aziz Royesh: What is your perspective on leadership—especially the leadership of girls and women?

Sahar Nikzad: When people hear the word leadership, they often think it means giving orders or commanding others. But through my experience in the Empowerment program, I’ve come to see it very differently. Leadership, to me, is not about ruling over others—it’s about guiding toward what is right and meaningful. I’ve come to realize that even now, in certain areas of my life—especially within my family—I can lead as a woman. Leadership doesn’t mean telling my brother or my mother what to do. It means helping shift mindsets and gently moving those around me toward understanding and support. For example, there were things I wanted to do that seemed strange to my family at first—like attending a course that was a bit far from home. At the beginning, they were worried and said things like, “These courses are useless.” But slowly, through conversation, through persistence, through the kind of leadership I learned, I shared my perspective with them. Over time, they started to accept it—and now they support me when I go to the courses I love.

A real-life example: I was passionate about learning public speaking and communication skills. When I first told my mother, she was skeptical. She said, “Why do you want to give speeches? Are you going to learn singing and dancing there?” That was her perception at the time. But I explained how one of my friends had attended the same course and now speaks beautifully—not just in public, but even with her family. Eventually, the day came when my mother attended my graduation ceremony and brought flowers herself. So for me, leadership means guiding others toward a shared understanding of the goals you believe in. It means bringing your family and community along with you—not by force, but through compassion, clarity, and consistent action.

Aziz Royesh: When you look 23 years ahead—when Sahar is 40 years old—what kind of person do you imagine yourself to be? If you try to visualize that version of yourself, as we say in Empowerment, what do you see?

Sahar Nikzad: Considering the changes I’ve seen in just the past four years —how my own mindset has evolved and how I’ve helped shift the thinking of others, especially within my own family— I can clearly envision myself reaching a place of real influence. I imagine myself in a position where I can confidently share my ideas with others —perhaps even holding a leadership role, like a presidency or another high-level position— where my voice is respected and taken seriously by those in government or other decision-making spaces. I’ve already started planning for that future, step by step. I believe that if I stay committed to these actions and goals, by the time I’m 40—or even sooner—I will arrive at the vision I hold today. I see myself as a spokesperson and ambassador for girls and their rights. I imagine a day when schools and universities are open again, when girls are thriving, and when every one of them has the freedom to pursue what they love —whether it’s becoming an actress, a singer, or a scientist. I see myself as someone who can speak freely, without fear, without being told her voice is forbidden. Someone who can share her story publicly and help others find their own. I imagine a world where no girl suffers because of her gender —and I see myself as one of the people who helped make that world possible, not through privilege, but through strength, vision, and the power I’ve built within myself.

Aziz Royesh: And just like that—when you imagine the world you’ll be living in, the society you’ve helped shape with your own hands—what does it look like to you?

Sahar Nikzad: I don’t see myself as a girl who is seeking freedom, progress, and prosperity only for herself. I imagine a world where my family, my friends, and many others around me are also striving for awareness, freedom, and equality in society. And it’s not just the people I know—there are so many others I may never meet, yet they’re walking the same path.

I see countless families working toward the same dream: to live freely and with dignity. I realize I’m not alone in this journey. There are many others beside me, and together, we are building a world where that dream becomes a beautiful, shared reality.

Aziz Royesh: Thank you, Sahar jan, for sharing such a beautiful story with us—a story of dreams, of lived experiences, and of hope.

Sahar Nikzad: Thank you, Ustad. Wishing you good health. I truly appreciate the time you gave, and the conversation we shared—it was a real joy for me.

Comments (0)

Leave a Comment